Australia's oldest rock painting is an anatomically accurate kangaroo

An unusual dating method revealed the painting's age.

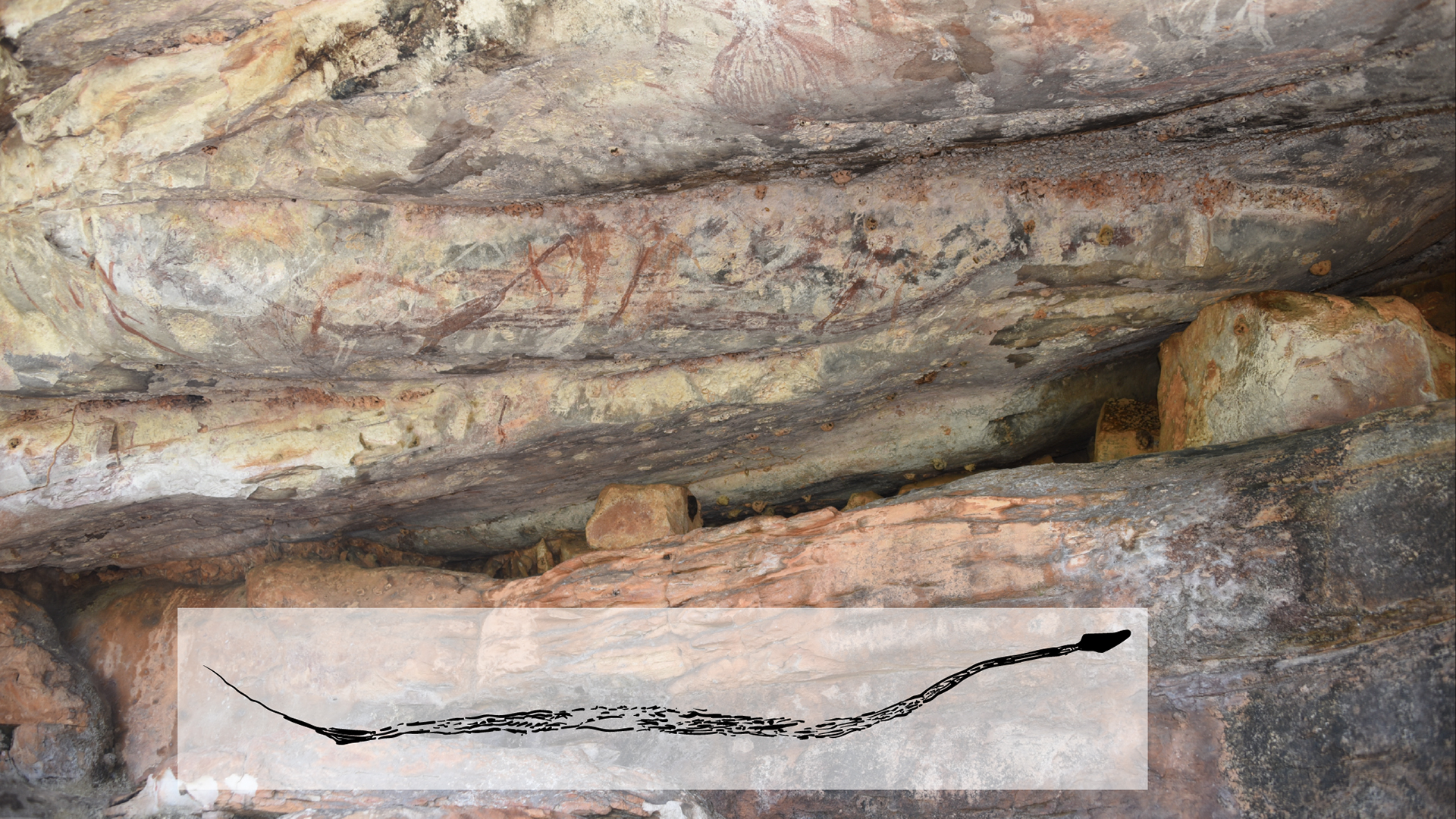

A nearly-life-size depiction of a kangaroo — realistic genitalia included — is the oldest known rock painting in Australia. Scientists recently pinpointed its age to 17,300 years ago with a technique that had never been used on Australian ancient art before: measuring radioactive carbon in wasp nests from rocks near the artwork.

The kangaroo painting extends across the ceiling of a rock shelter and spans nearly 7 feet (2 meters), which is roughly the height of a modern kangaroo. This and other paintings in northwestern Australia's Kimberley region share certain stylistic features with the earliest cave art from Europe and Asia, the researchers reported. Very old animal paintings such as these are typically life-size (or close to it); they represent anatomy in a similar way, and their outlines are only partly filled-in with sketched lines. Because of these features, the paintings were thought to be among Australia's oldest.

However, to precisely date such art, scientists often turn to radiocarbon dating, which measures the ratio of different versions, or isotopes, of carbon in an object. But it requires organic material, which is scarce in rock paintings.

Related: Photos: Ancient rock art of Southern Africa

In places such as the Chauvet Cave in France, ancient drawings are etched in charcoal and hidden deep inside limestone caverns, preserving the organic matter in the charcoal pigments and making radiocarbon dating possible. Chauvet art has been directly dated to between 34,000 and 29,000 years ago, the study authors wrote.

But such preservation is exceptionally rare, and the paintings thought to be Australia's oldest are usually exposed to the elements, "in more open rock shelters in sandstone country," said lead study author Damien Finch, a doctoral candidate in the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

"Here, the pigment used is invariably an iron oxide that cannot be dated directly," Finch told Live Science in an email. "If charcoal was used as a rock art pigment in ancient Aboriginal rock art, then we have yet to find any surviving examples in Australia."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So the scientists turned to mud wasps nests built under, above and near the art. Over a period of five years, they collected and analyzed 27 nests associated with 16 different rock paintings in Drysdale River National Park, painted in the region's oldest style. "We then use the pattern of all the maximum and minimum dates that apply to paintings of the same style, to estimate the period when they were painted," he explained. "The accuracy of this estimate increases as more and more nests are dated."

They found that most of the paintings were likely made between 13,000 and 17,000 years ago. As for the kangaroo painting, six nearby nests provided both minimum and maximum dates, enabling the scientists to estimate its age.

For millennia, people have used art to convey their perspective on the world around them; the oldest known animal art — an exceptionally hairy pig, found in a cave in Indonesia — dates to approximately 45,000 years ago. While it's impossible to know for sure what compelled the earliest human artists to create representational paintings, their work literally paints a picture of the long-ago ecosystems they inhabited, complementing scientific evidence about climate and sea levels "as well as the plants and animals available at that time," Finch said.

"Now, for the first time, we can combine what we see in the paintings with what we know about the environment as it existed at the same time, around the end of the last ice age," Finch said. "I am sure future researchers will draw these threads together with what we know now about the age of the rock art."

Putting dates to ancient art is also critical for reconstructing the missing pieces of Australia's past that were shaped by Aboriginal people thousands of years ago, said Cissy Gore-Birch, chair of the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation in Australia, which manages land administration on behalf of the Balanggarra People.

"It's important that Indigenous knowledge and stories are not lost and continue to be shared for generations to come," Gore-Birch said in a statement.

The findings were published online Monday (Feb. 22) in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.