Famous Irish tomb yields a surprise — a king born of brother-sister incest

Elite dynasty used incestuous marriage to distinguish themselves.

Ancient genetic material extracted from human bones buried in Ireland's famous Newgrange tomb come from a Neolithic man, likely a king, whose parents were probably brother and sister, according to new research.

The discovery suggests Neolithic Ireland was ruled about 5,000 years ago by an elite dynasty that used incestuous marriage to distinguish themselves from ordinary society — like the pharaohs of ancient Egypt and some Inca royalty in Mesoamerica.

In a study published Wednesday (June 17) in the journal Nature, a team led by scientists at Trinity College Dublin examined genetic material from 42 people buried at Neolithic sites in Ireland, dating from between 5,800 and 4,500 years ago, and two people from earlier Mesolithic burial sites dating from 6,100 to 6,700 years ago..

Related: Photos: Ireland's Newgrange passage tomb and henge

They found that an individual buried in the most ornate recess of the Newgrange passage tomb — one of the earliest Stone Age monuments in Europe — was an adult male whose parents could only be first-degree relatives.

That means they were probably a brother and sister — or perhaps a parent and child, although that's extremely rare throughout history.

"We inherit one copy of the genome of our mother, and one from our father, and we can compare these two copies of the genome in this individual," said lead study author Lara Cassidy, a geneticist at Trinity College Dublin. "Basically, what we saw was that they were extremely similar."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the researchers calculated the inbreeding coefficient, which is based on how much DNA is shared by both parents, they found it was 25 percent: "That's a sign of a mating between first-degree relatives, who share 50 percent of their DNA," Cassidy told Live Science.

Ancient dynasty

Incestuous mating between brothers and sisters is a near-universal taboo in human societies for both cultural and biological reasons, Cassidy explained.

The only social acceptance of brother-sister marriage was among elites, she said — typically within a deified royal family, such as the Egyptian pharaohs.

"It is a way that elites can separate themselves — they get to break a taboo, they get to break a social convention that others aren't allowed to," Cassidy said.

As a result, sibling marriages were often restricted to a single royal family perceived as godlike or divine. And while the ornate burial of the individual at Newgrange suggests the social acceptance of his parentage, genetic studies of other Neolithic burials in Ireland show no signs of such interbreeding, she said.

Related: 7 bizarre ancient cultures that history forgot

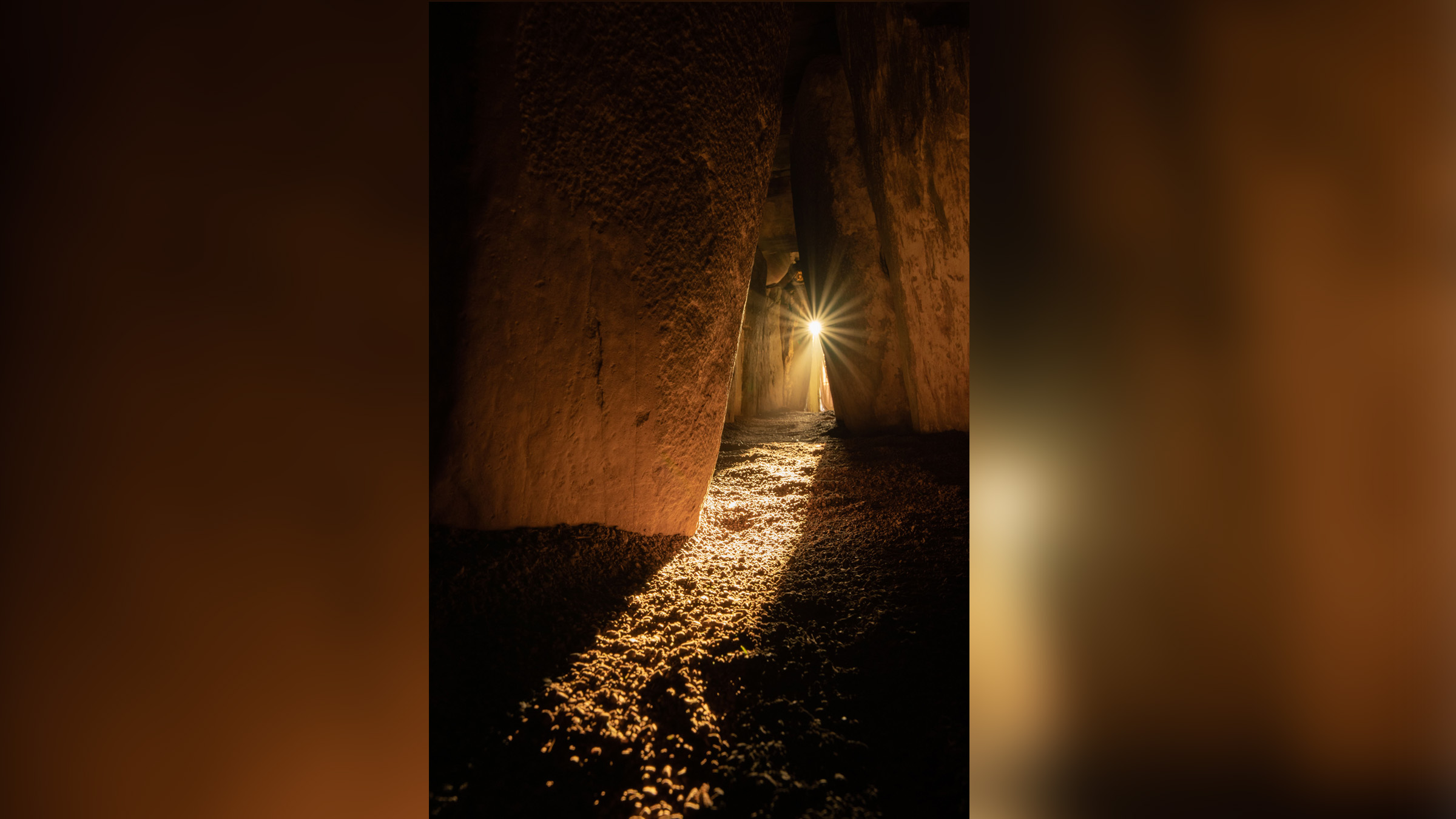

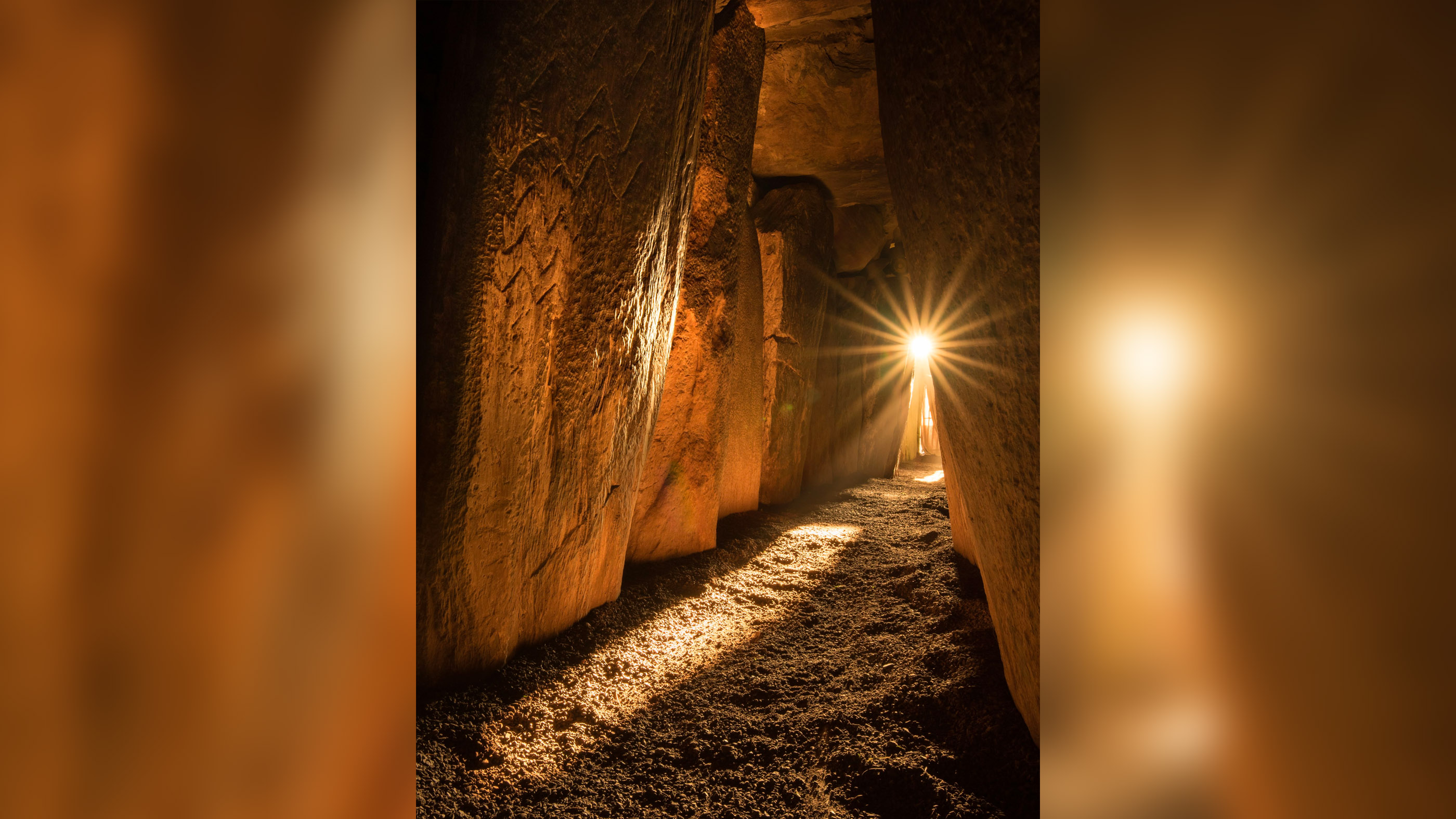

The discovery also echoes a local myth involving a particular solar phenomenon at Newgrange, the most elaborate passage tomb in the Brú na Bóinne Neolithic cemetery north of Dublin, where the rising midwinter sun casts a shaft of light deep inside to illuminate the ceremonial recesses within.

According to legend, an ancient king tried to build a high tower in a single day at nearby Dowth, about a mile from Newgrange, with the help of magic from his sister that stopped the sun in the sky.

But the king broke the spell and started the sun moving again by committing incest with his sister; as such, the 11th-century Irish place-name for the passage tomb at Dowth is Fertae Chuile, which can be translated as "Hill of Sin" or "Hill of Incest," the researchers wrote.

Neolithic Ireland

The study of ancient Irish genomes also revealed that the man buried in the Newgrange passage tomb was distantly related to an individual buried in a Neolithic passage tomb at Carrowmore in County Sligo, more than 90 miles (140 kilometers) away in the west of Ireland.

Individuals buried in the tombs were also more closely related to each other than to other members of the population, Cassidy said, while a chemical analysis of their bones also suggests they ate more meat than was usual at the time.

Related: What's the difference between a second cousin and a first cousin once-removed?

"It looks like this is an extended kin group who had access to elite burials," she said. "This is happening in a lot of different areas of Ireland over many centuries."

The researchers also examined the similarities and differences between the Neolithic inhabitants of Ireland and the earlier indigenous peoples, who were represented by the two Mesolithic burials.

Their results support the theory that Ireland was colonized about 5,800 years ago by Neolithic farmers, perhaps from the Iberian Peninsula, who eventually replaced the indigenous hunter-gatherers.

But a single Neolithic individual in the west of Ireland was found to have hunter-gatherer genes in his recent family tree, suggesting the indigenous peoples were assimilated rather than exterminated, Cassidy said.

The researchers also found genetic evidence of the earliest-known case of Down Syndrome, in a male infant buried in the Poulnabrone tomb in Ireland's County Clare and dating from more than 5,500 years ago.

Analysis of certain chemical isotopes shows that the infant was fed breast milk, and he was given a prestige tomb burial — probably a signifier of elite descent, Cassidy said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.