Who were the Knights Hospitaller?

The Knights Hospitaller was a humanitarian order of holy warriors during the Crusades who served as inspiration to the Knights Templar.

The Knights Hospitaller arose from the victory of the First Crusade (1096-1099) and the need to protect pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. The Hospitaller Knights were the first of the burgeoning Medieval religious orders to receive official Papal backing, achieved in 1113. After the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, in 1291, the Hospitallers acquired the Greek island of Rhodes as their base and continued operations in the Near East until 1522.

In 1530, they established a new base, this time in Malta, and remained there until 1798. Although the Hospitallers splintered and scattered into various groups after this, their legacy is to be found in the present day via such organizations as St. John’s Ambulance and the Knights of Malta.

Origins and creation

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, abbreviated to the Knights Hospitaller or Hospitallers, can trace its origins to a volunteer group running a hospice created in the Holy Land by Italian merchants trading with Palestine, who hailed from the coastal towns of Amalfi and Salerno, in 1070 as Jonathan Riley-Smith, the late Dixie professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge, wrote in "The Knights Hospitaller in the Levant, C.1070-1309" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, originally published in 1977).

The hospice was located on the site of a church consecrated to St. John close to the Holy Sepulchre. From the location, the order took their name. In the early years of its proto existence, the loose network of hospices, which served all faiths and both men and women, in separation quarters, was overseen by the Benedictine monks from the St. Mary of the Latins, a Catholic-run complex of church, monastery, market place and convent built during the era of Muslim rule and upon the ruins of an older facility destroyed in 1009 by Egyptian Caliph al-Hakim (985-1021), according to Helen J. Nicholson, former head of the History Department at Cardiff University, in "The Knights Hospitaller" (Boydell Press, 2006).

Before the First Crusade, Jerusalem was controlled by various Muslim rulers of the Fatimid Empire and the Seljuk Turkish Empire. Nicholas Morton, professor of history at Nottingham Trent University explained to Live Science, via email, the complicated and dangerous situation Christian pilgrims faced and the beginnings of the Hospitallers. "Initially this institution was neither large nor a formal religious order, just a small group of pious individuals providing help for sick and weary travelers. At this time Jerusalem lay on a frontier of war between the Fatimid Empire [centered on Egypt] and the Seljuk Turkish Empire [which spanned much of the Near East] and the city changed hands repeatedly. Nevertheless, the rulers of both these empires permitted these early Hospitallers to pursue their vocation and the hospital continued to support pilgrims up to the arrival of the First Crusade in 1099."

Favorable conditions in the aftermath of the First Crusade and the creation of the Crusader States resulted in the hospice being granted independence from the Benedictine monks and it was allowed control over its own affairs, according to Riley-Smith. The influx of pilgrims in the years following the First Crusade further added to its development as an important fixture in the Latin East.

Rory MacLellan, a postdoctoral research fellow for Historic Royal Palaces at the Tower of London, told LiveScience in a telephone interview, "Being a hospice, that doesn’t necessarily mean what it does today, so it’s this mixture of, almost like a youth hostel for people traveling, but it also provides medical care, like a hospital would today, and it’s also a bit like an alms house, like sheltered living for homeless people. It’s a mixture of all these different things. They were called the Hospitallers, but it wasn’t solely medical care they provided."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is likely the Hospitaller order’s founder, Blessed Gerard (1040-1120), of whom very little is known, was a Benedictine monk, described by Nicholson as a, "venerable and pious man," who came to the Holy Land circa 1080 and was attached to St. Mary of the Latins. Blessed Gerard and his brethren’s good works caring for pilgrims, the sick and the homeless led to the first ruler of Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon (1060-1100), granting the Hospitallers various properties. His successor, Baldwin I (c.1060-1118), also made donations and helped establish their credentials with the nobility and the Catholic church.

By 1112 the order received financial support from the King of Jerusalem and the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Blessed Gerard received further support on Feb. 15, 1113, when Pope Paschal II (c.1050-1118), recognized the order in the papal bull, Pie Postulatio voluntatis (The Most Pious Request), confirmed by Pope Calixtus II in 1119, according to Nicholson. It placed the Hospitallers under the direct protection of Rome, granted its right to appoint its own Grandmaster, they did not have to pay tithes and its brothers and sisters were bound by vows of chastity, poverty and obedience.

Organization and growth

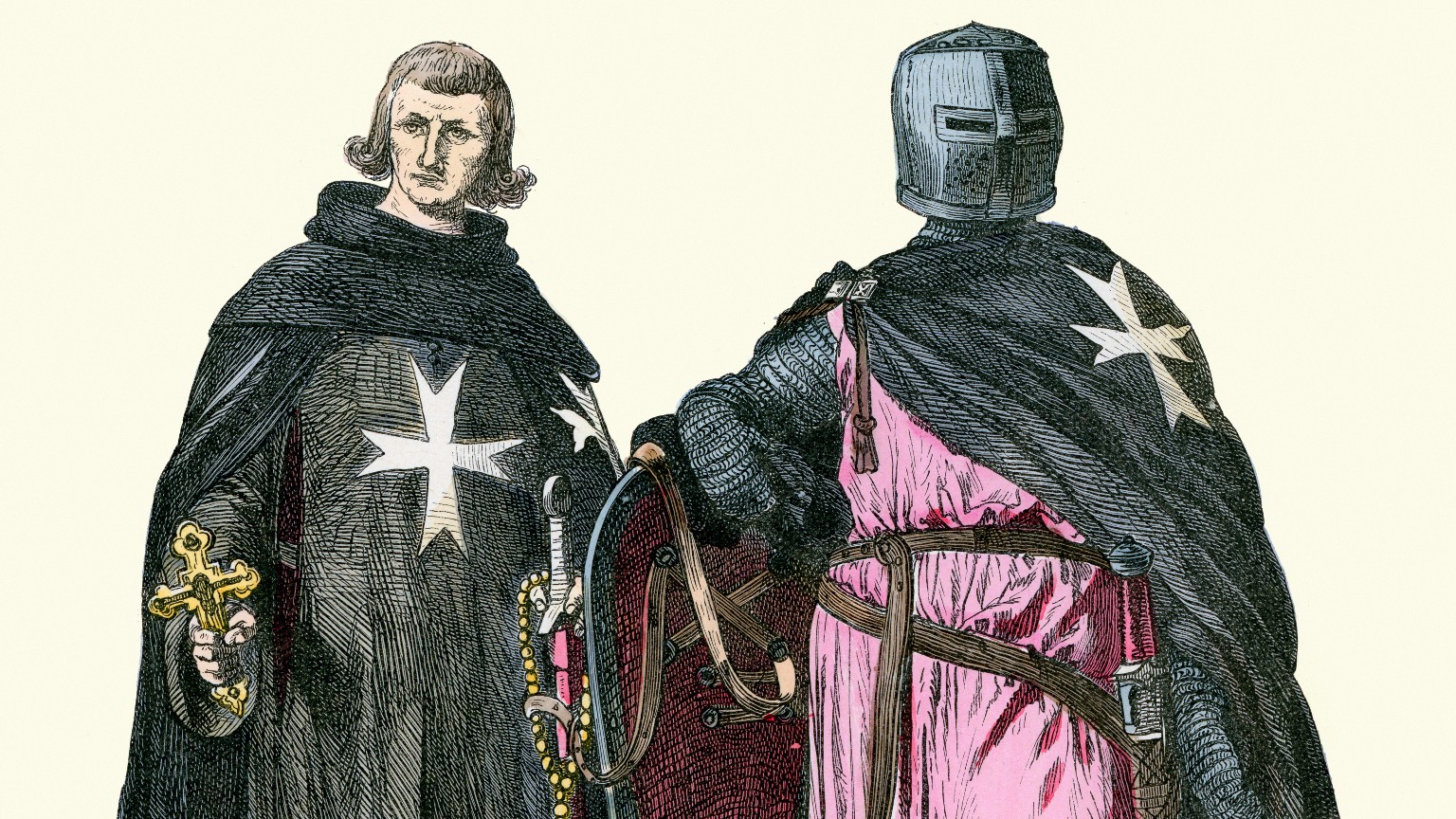

The Hospitallers were classed as knights, clergymen and serving brethren. The knights class hailed from European aristocracy. The Hospitallers eventually militarized but it is unclear when precisely. The Hospitallers originally wore black surcoats with the Amalfi cross eight-point star as their insignia according to the Museum of the Order of Saint John, distinguishing them from other orders, such as the Knights Templar, who wore a white surcoat with red flag.

"One of the big problems the Crusader States had, is there was quite a shortage of manpower, as most of the Crusaders, after the First Crusade, went home," MacLellan explained of the backdrop that led to the military wing of the Hospitallers developing as a necessity due to regional strife and the demands of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. "Eventually, you have the Hospitallers militarizing because they’re going to be there permanently, plus they were not going to come for a year, crusade, and then go home.

"We don’t know when exactly they do militarize, but they had certainly done it by 1126. We find one of the Hospitallers in the army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem as a Constable. Later records talk about the Hospitallers fighting battles between 1120-60. Although they’re an older organization than the Templars, they don’t actually militarize until after the Templars are created in 1120."

Morton adds that the actual date of the militarization of the Hospitallers is unclear, but it must be before 1136. "The Hospitallers were clearly playing an important role in the kingdom’s defense because in this year they accepted responsibility for a newly-constructed frontline fortress called Bethgibelin," he said.

As they performed dual functions as humanitarians and warrior-monks, they admitted men and women as Hospitaller brothers and sisters. Their initial holdings were situated in the Crusader States, such as forts and a variety of estates but they grew rapidly and received gifts of land and other donations from all over Europe.

Morton explain the setup and how it worked. "The Hospitallers grouped these properties into 'commanderies', which were essentially clusters of local assets —whether farms, mines, salt pans, mills, churches etc — co-ordinated around a central administrative hub (normally the largest estate or house owned by the order in that area).

"The rapid growth of the Hospitallers’ infrastructure in the west brought them enormous wealth which they could then despatch to the east to support their military and medical activities in the kingdom of Jerusalem. With these resources, the order also expanded its role in the Crusader States, building its presence in the kingdom of Jerusalem and also providing troops and garrisons to protect the more northerly territories of the county of Tripoli and the principality of Antioch."

Hospitallers after the Crusades

When the Ayyubid Sultanate under Saladin recaptured Jerusalem in 1187, and the last of the Crusader States fell completely by 1291, the Hospitallers retreated to the island of Cyprus. In 1309, they acquired Rhodes, the Greek island off the Turkish mainland and used it as a base of operations. The Hospitallers became widely known as the Knights of Rhodes and they renewed their fight against Muslim empires around the Mediterranean, this time on the high seas. After the dissolution of the Knights Templars, in 1312, the Hospitallers were granted lands and donations from the disgraced group by Pope Clement V (c.1264-1314), though had certain difficulties claiming them.

With the failures of religious-military orders in defending the Crusader States, the Hospitallers were saved from a similar doomed fate. "The Hospitallers had advantages which the Templars lacked," Morton said. "Their medical vocation meant that, even when their military activities failed, they could still present themselves to contemporaries as performing an important role in society. Moreover, soon after the fall of Acre, in 1291, the Hospitallers relocated their headquarters to Cyprus and built up a naval force with which to continue their wars against the Mamluk Empire and other neighboring powers.

"The Templars also moved to Cyprus and built up a naval force but, where their attempts to re-assume the offensive failed badly, the Hospitallers proved more successful. In 1306 Hospitaller forces began the conquest of the Isle of Rhodes, then technically a possession of the Byzantine Empire albeit under Genoese control. By 1310 the Hospitallers had full control over the island which in later years they used as a base from which to attack ships and territories belonging to the Turkish rulers of Anatolia."

Rhodes had important shipping links and connections to other parts of the Mediterranean and the Knights of Rhodes also captured small islands such as Kos and ran their affairs from a fortification located in Rhodes harbor. In 1523, their time on Rhodes ended, when the Turkish ruler, Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566) captured the island, using 400 ships and 10,000 men to win a decisive battle. In 1530, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, bestowed the island of Malta upon the order, in return for a yearly gift of a falcon to the Viceroy of Sicily.

As the Knights of Malta, they took part in decisive battles against Turkish naval forces, often in league with Catholic countries and rulers, such as the 1571 Battle of Lepanto, and proceeded to build Malta’s capital, Valetta, named in honor of their grand master, Jean Parisot de la Valette (c1495-1568).

MacLellan describes this period of Hospitaller history as a case of the order being too good at their job. "For the periods on Rhodes and Malta, they were just very good at what they did. They were very successful at naval campaigns and combating piracy. Just before they were kicked off Malta by Napoleon in 1798, they had cut back on their naval patrols as there weren't enough pirates for them to fight."

Do the Hospitallers exist today?

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) evicted the Knights of Malta. The Treaty of Amiens in 1802 returned them to the Mediterranean island but this was upturned in 1812, when the Treaty of Paris gave Malta to Great Britain.

From here, the order splintered off to various European countries and essentially gave up its militaristic wing. It continued as a humanitarian and caregiving organization. "They do have this weird period after Malta, where one branch goes off to Russia, where they let the Tsar be their Grandmaster, which is a bit odd," MacLellan explained. "Then they have a few decades where they don’t actually have a Grandmaster anymore and not quite given the same status. Since then, it’s their humanitarian work that keeps them going. I think I saw one stat that said after Oxfam and Red Cross, if you combine all the successor groups of the Hospitallers, they’re the third biggest charity provider in the world today, so it’s a significant part of what keeps them going."

A host of modern organizations maintain continuity with the Hospitallers and the Knights of Malta. Unlike the far-right revival of the Templars, the 21st century iterations of the Medieval order have maintained a humanitarian tradition and have attracted no such controversy. The Sovereign Military Order of Malta, a Catholic group based in Rome, with over 13,500 members, is active in 120 countries around the world, upholding the tradition of caregiving and engaging in social projects. Its motto is "Tuitio Fidei et Obsequium Pauperum" (nurturing, witnessing, and protecting the faith; and serving the sick and the poor."

In 2013, Israeli archaeologists rediscovered a 3.7-acre portion of the sprawling Hospitaller complex, with its 18-feet (5.5-meter) ceilings and ribbed vault design, close to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, in Jerusalem’s Christian Quarter, known as Muristan. In its heyday, it could house 2,000 patients and also functioned as an orphanage, with children growing up to become part of the order.

Additional resources and reading

If you want to know more about the religious orders who took part in the Crusades, then you'll definitely want to read about the Knights Templar and how they became a dominant force in the various conflicts.

Excitingly, new information and archaeological discoveries around the Crusades are being unearthed frequently. For instance, the battlefield where Richard the Lionheart defeated Saladin was unearthed in Israel in 2020.

Bibliography

"The Knights Hospitaller in the Levant, C.1070-1309" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

"The Knights Hospitaller" (Boydell Press, 2006)

Martyn Conterio is a freelance writer, journalist and film critic based in London in the United Kingdom. He is a regular contributor to Live Science's sister publications All About History and History of War magazines, as well as Templars. Martyn also contributes to BFI and NME, Total Film and the Guardian, and is the author of Devil’s Advocates: Black Sunday (2015) and Mad Max (Constellations) (2019).