Lab-Made Embryos Could Save Northern White Rhinos After Last Male Dies

The last two northern white rhinoceroses on Earth will never bear young, but they may have genetic offspring nonetheless.

Just two northern white rhinoceroses exist in the world. Now, though, this critically endangered subspecies has a new, slim chance at survival: two lab-created embryos that could grow to maturity, according to an announcement made Wednesday (Sept.11).

The international team of researchers has been working to save the northern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) for years using in-vitro fertilization. Now that researchers have successfully fertilized two of these eggs, the next step would be to implant the lab-created embryos in the uteruses of members of a closely related subspecies, the southern white rhino.

"The entire team has been developing and planning these procedures for years," Thomas Hildebrandt, a biologist from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Germany, said in a statement. "Today, we achieved an important milestone on a rocky road which allows us to plan the future steps in the rescue program of the northern white rhino."

Related: See Photos of the Last Standing Northern White Rhinos

Last of their kind

The northern white rhinoceros likely went extinct in the wild in 2007 or 2008. Though a small number of the animals survived in zoos, most of the living individuals were aging or had health problems that precluded them carrying young. In 2018, the last male northern white rhino, Sudan, died, leaving only two members of the species, both female, alive.

The new embryos count those two living rhinos as their mothers. The maternal rhinos, Najin and Fatu, were both born at Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic and now live at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. Neither will be able to carry their embryos to term. Najin is too old, and Fatu has uterine problems that make pregnancy impossible.

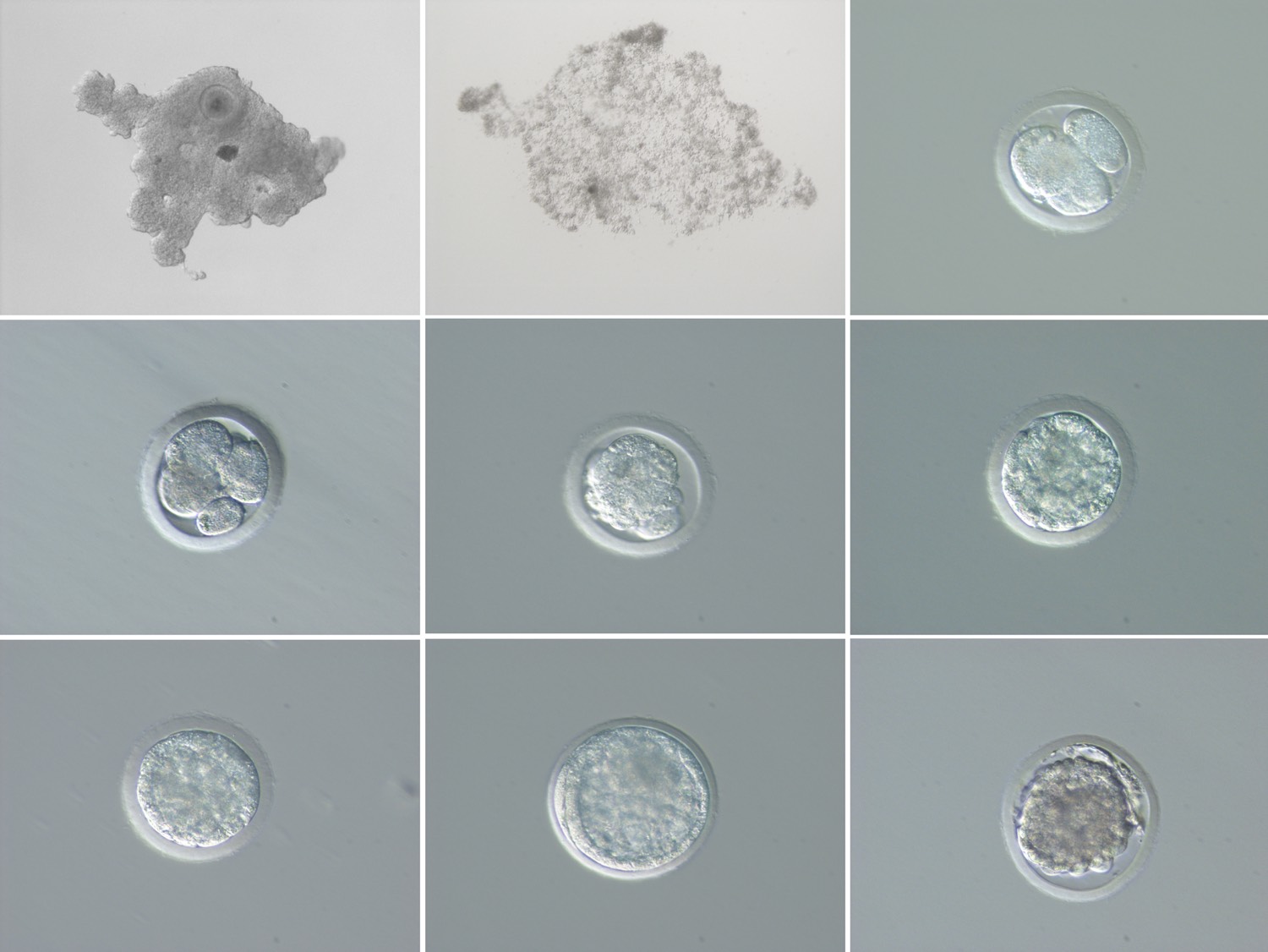

But in late August, scientists successfully harvested eggs from both female rhinos. The researchers then used a procedure called intra cytoplasm sperm injection to fertilize the eggs with frozen sperm from two northern white rhino males named Suni and Saut. Suni died in 2014, and Saut died in 2006.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: In Photos: The Last 5 Northern White Rhinos

Of the 10 eggs harvested, seven were suitable for fertilization, according to one of the researchers involved, Cesare Galli, of Avantea Laboratories in Cremona, Italy. Ultimately, only two matured into viable embryos. Both of those were created with Fatu's eggs and Suni's sperm. The embryos have now been frozen to preserve them for future transfer.

Saving a subspecies

To bring the embryos to term, scientists still have to perfect the art of embryo transfer in rhinos. Researchers will also have to find a healthy southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) or two to carry the pregnancy.

"Five years ago, it seemed like the production of a northern white rhino embryo was [an] almost unachievable goal — and today we have them. This fantastic achievement of the whole team allows us to be optimistic regarding our next steps," Jan Stejskal, the director of communications and international projects at the zoo where Najin and Fatu were born, said in the statement.

To truly bring back the northern white, though, will take more than a few successful rounds of in vitro fertilization. Scientists have only two living reservoirs for eggs and have stored sperm from only four northern white rhinoceros bulls. That leaves little genetic diversity for resurrecting the species. But tissue banks do have nongamete tissues (meaning any tissue except the sperm and egg) stored from other northern whites, which would expand the gene pool to 12 rhinos. Researchers are now working on stem cell technology to transform these regular tissue samples into sperm and eggs.

- 6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life

- Species Success Stories: 10 Animals Back from the Brink

- 15 of the Largest Animals of Their Kind on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.