Scientists discover largest bacteria-eating virus. It blurs line between living and nonliving.

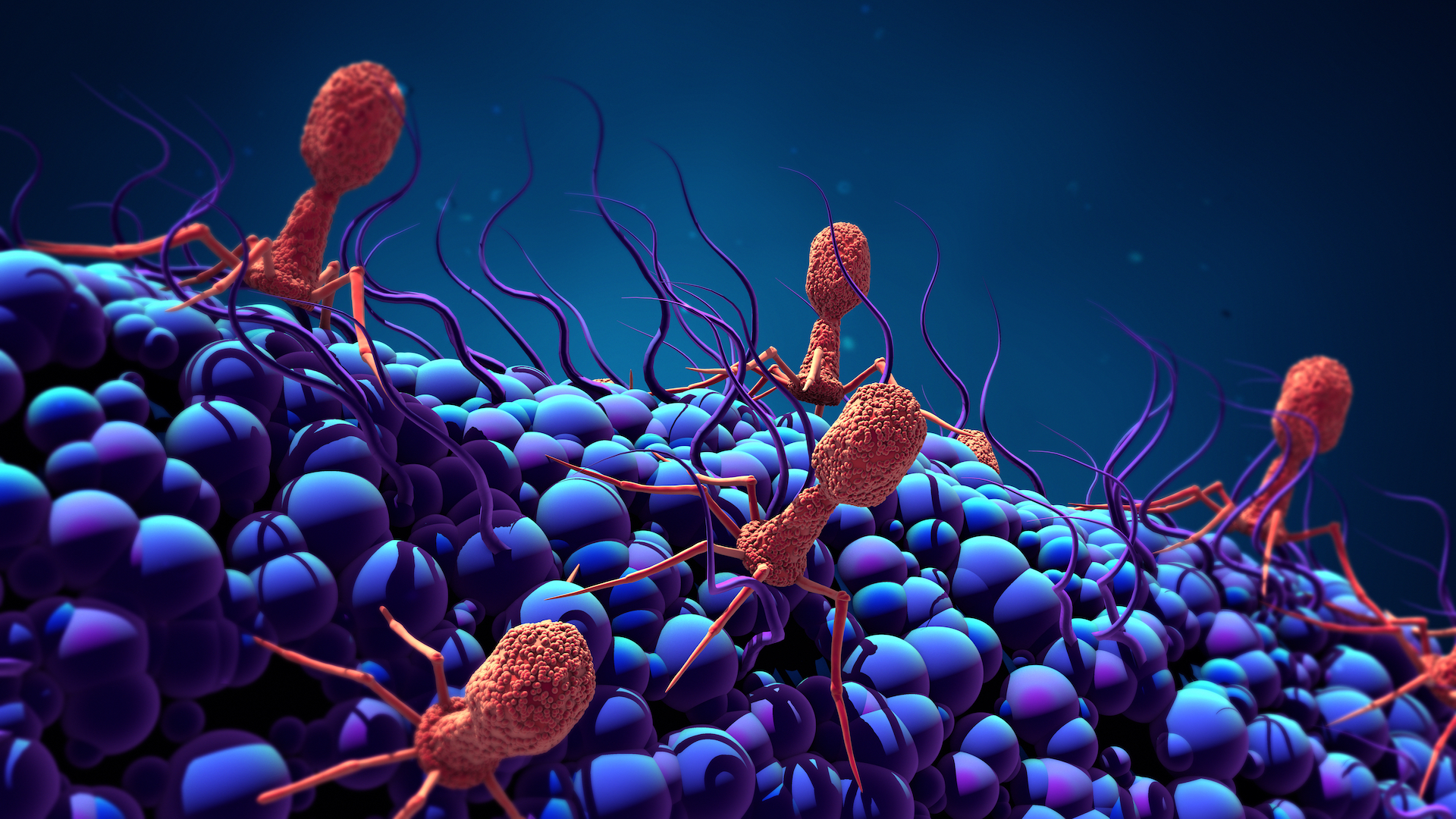

Huge bacteria-killing viruses lurk in ecosystems around the world from hot springs to freshwater lakes and rivers. Now, a group of researchers has discovered some of these so-called bacteriophages that are so large and so complex that they blur the line between living and nonliving, according to new findings.

Bacteriophages, or "phages" for short, are viruses that specifically infect bacteria. Phages and other viruses are not considered living organisms because they can't carry out biological processes without the help and cellular machinery of another organism.

That doesn't mean they are innocuous: Phages are major drivers of ecosystem change because they prey on populations of bacteria, alter their metabolism, spread antibiotic resistance and carry compounds that cause disease in animals and humans, according to the researchers in a new study, published Feb. 12 in the journal Nature.

Related: Going Viral: 6 new findings about viruses

To learn more about these sneaky invaders, the researchers searched through a DNA database that they created from samples they and their colleagues collected from nearly 30 different environments around the world, ranging from the guts of people and Alaskan moose to a South African bioreactor and a Tibetan hot spring, according to a statement.

From that DNA, they discovered 351 huge phages that had genomes four or more times larger than the average genome of phages. Among those was the largest phage found to date with a genome of 735,000 base pairs — the pairs of nucleotides that make up the rungs of the DNA molecule's "ladder" structure — or nearly 15 times larger than the average phage. (The human genome contains about 3 billion base pairs.)

These phages are "hybrids between what we think of as traditional viruses and traditional living organisms," such as bacteria and archaea, senior author Jill Banfield, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of Earth and planetary science and of environmental science, policy and management, said in the statement. This huge phages' genome is much larger than the genomes of many bacteria, according to the statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The authors found that many of the genes coded for proteins that are yet unknown to us. They found that the phages had a number of genes that are not typical of viruses but are typical of bacteria, according to the statement. Some of these genes are part of a system that bacteria use to fight viruses (and was later adapted by humans to edit genes, a technique called CRISPR-Cas9).

Scientists don't know for sure, but they think that once these phages inject their DNA into bacteria, the phages' own CRISPR system strengthens the CRISPR system of the bacteria. In that way, the combined CRISPR system could help to target other phages (getting rid of the competition).

What's more, they found that some of the phages had genes that coded for proteins necessary for the functioning of ribosomes — a cellular machine that translates genetic material into proteins (the proteins are the molecules that carry out DNA's instructions). These proteins aren't typically found in viruses, but they are found in bacteria and archaea, according to the statement.

Some of these newfound phages may also use the ribosomes in their bacteria host to make more copies of their own proteins, according to the statement.

"Typically, what separates life from nonlife is to have ribosomes and the ability to do translation; that is one of the major defining features that separate viruses and bacteria, nonlife and life," co-lead author Rohan Sachdeva, a research associate at UC Berkeley, said in the statement. "Some large phages have a lot of this translational machinery, so they are blurring the line a bit."

- The 9 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 28 devastating infectious diseases

- 5 ways gut bacteria affect your health

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.