Google Earth reveals the world's largest geoglyph

A set of sinuous lines found in the Thar Desert of India may be the largest geoglyph ever discovered.

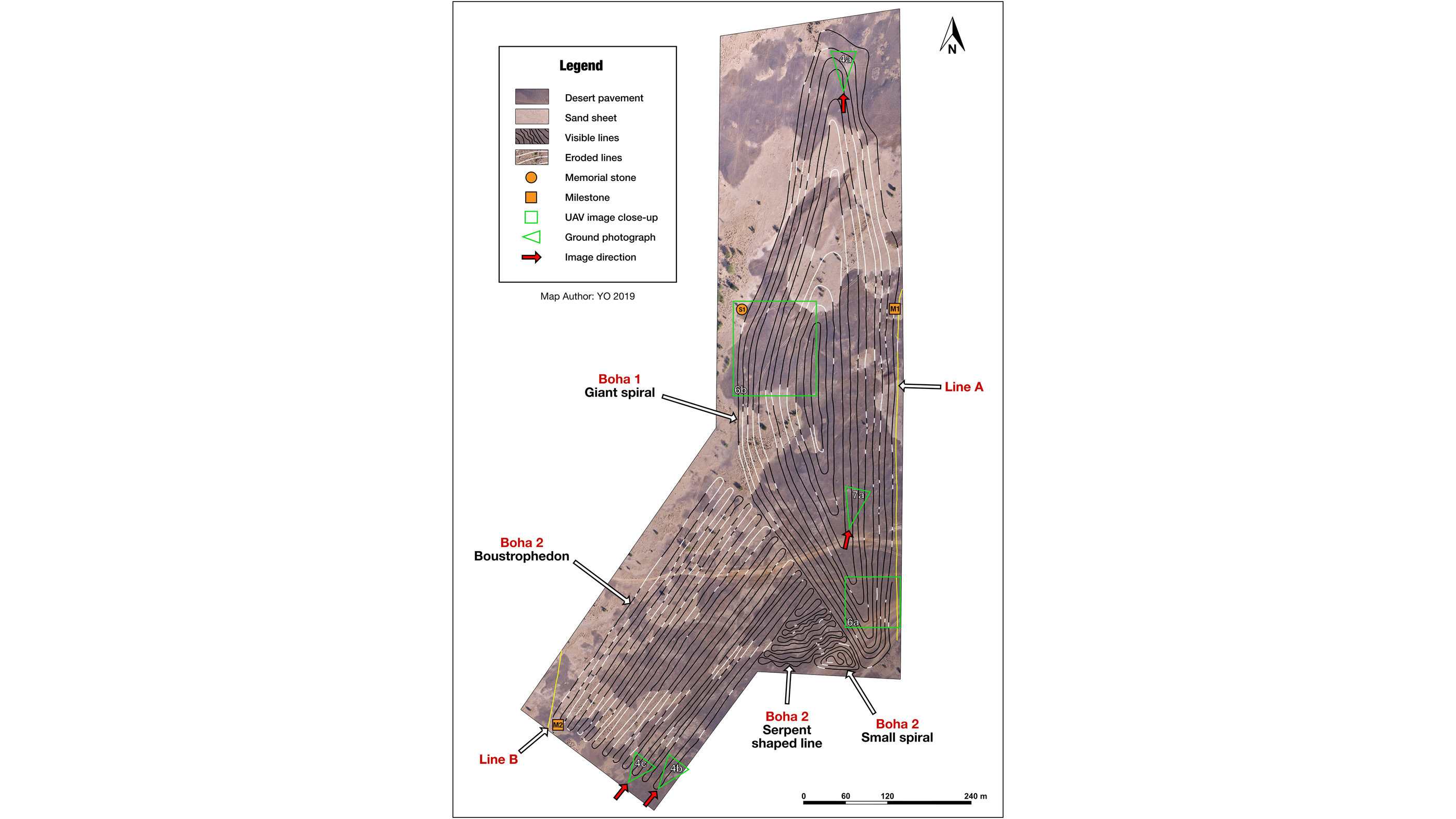

Geoglyphs, which are sprawling designs formed with earth or stone, have not previously been found in India, though they are known from other deserts in Peru and in Kazakhstan. The Indian glyph consists of several spirals and a long, snaking line that doubles back on itself again and again. All told, the patterns cover 51 acres (20.8 hectares) of the arid region near the border with Pakistan. A hike along all the lines would make for a journey of 30 miles (48 kilometers).

It's not clear why the lines were made, though they are situated near several rock cairns, or stacks, and memorial stones, the latter carved with images of the Hindu deities Krishna and Ganesha. The lines may have some sort of religious or ceremonial meaning, discoverers and independent French researchers Carlo Oetheimer, and Yohann Oetheimer, wrote for the upcoming September issue of the journal Archaeological Research in Asia. The overall pattern is not visible from the ground, as there is no high point nearby and the terrain is flat. Only by scouting the region on Google Earth were the Oetheimers able to discover the geoglyphs.

Related: Photos: Ancient circular geoglyphs etched into the sand in Peru

Monumental lines

The researchers first discovered the lines on Google Earth in 2014 while conducting a virtual survey of the region. In 2016, they visited a collection of intriguing sites. Several promising spots turned out to be furrows for failed tree plantations. But near the village of Boha, the researchers found patterns that had nothing to do with farming.

"The Boha lines stand out in regard to their monumental size, their shape (a giant spiral, a boustrophedon and a small, ovoid spiral, plus some portions of lines related to the main motives) and the orientation of the giant spiral," the Oetheimers wrote in an email to Live Science.

Related: 25 strangest sights on Google Earth

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A boustrophedon refers to a line that doubles back on itself, first going from right to left and then left to right, in an alternating pattern. Some ancient written languages, including ancient Greek and Etruscan (from what is now Italy), were written in this back-and-forth style.

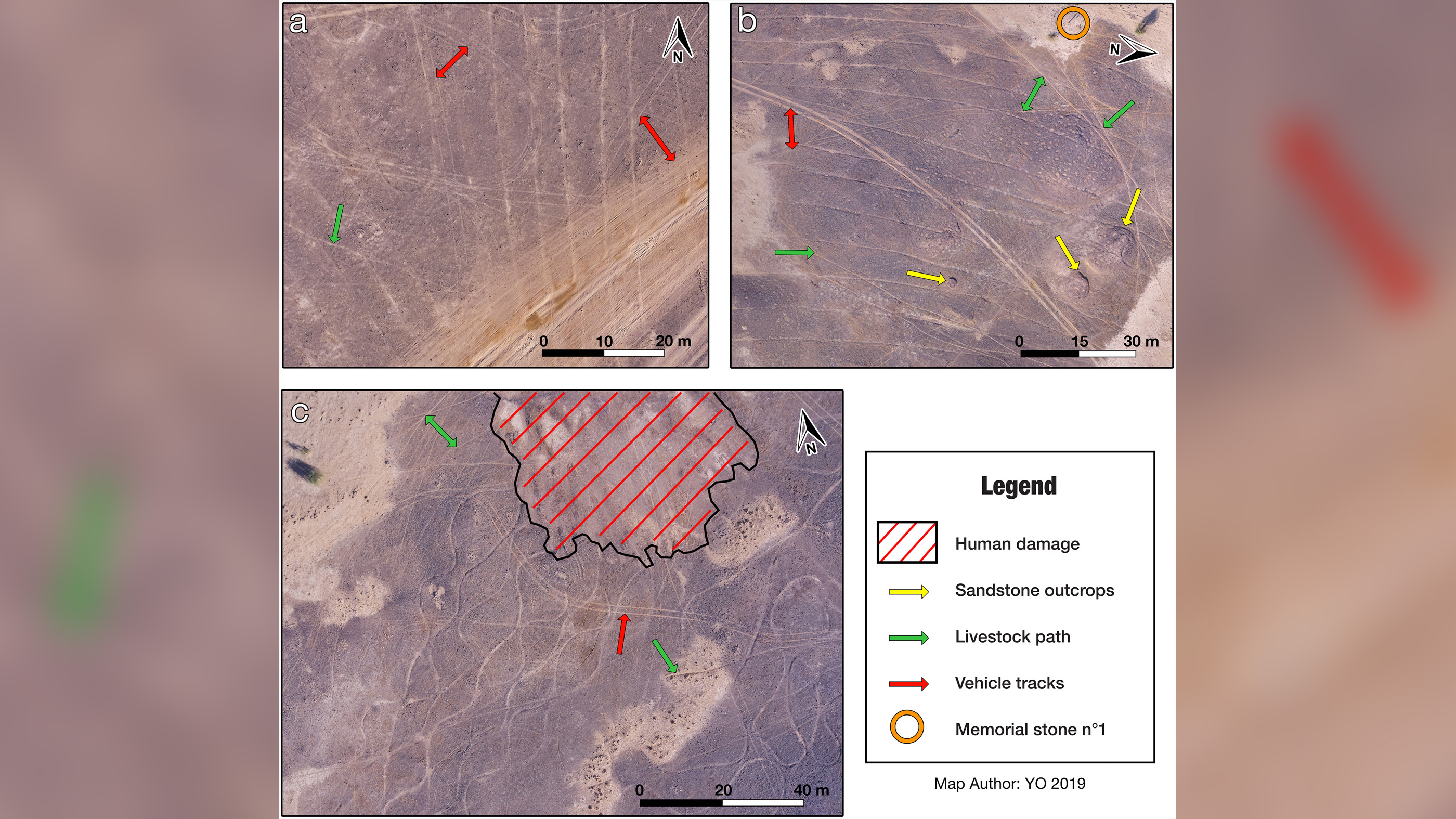

For all their size, the lines are fairly subtle on the ground. They are dug into the desert soil about 4 inches (10 centimeters) deep and are just 8 to 20 inches (20 to 50 cm) wide. Though the researchers aren't sure how the lines were made, they could have been formed with a plow pulled by a draft animal, like a camel.

A desert mystery

Based on weathering and the sparse vegetation growth in and around the lines, the researchers estimate that the designs are around 150 years old, or perhaps as old as 200 years. That older age would put them in line with the age of the memorial stones found nearby. The area is uncultivated, the Oetheimers told Live Science, with no available water for irrigation nearby; the land is currently used to graze goats and sheep.

"[T]he shape of the lines are not fields," the Oethemiers wrote to Live Science. "They are definitely designs."

The largest of the geoglyphs is a giant spiral covering 0.05 square miles (0.13 square kilometers), which would measure 7.5 miles (12 km) if stretched out into a straight line. Nearby is a serpent-shaped line that's 6.8 miles (11 km) long and the boustrophedon-style pattern, which consists of 23 nearly parallel lines. Those lines total 5.7 miles (9.2 km). There is also another small spiral and a number of faint lines nearby, suggesting that the geoglyphs were once much larger.

There are a total of nine stone structures in and around the lines; the largest is a pillar just over 5 feet (1.6 m) tall. Three of the structures are rock cairns, four are carved memorial stones with inscriptions that are still being studied and three others are simple rectangular stones used for memorials or landmarks. The final stone is a sati stone, which was erected to memorialize a widow who threw herself on her husband's funeral pyre after his death in battle.

But old carvings and memorials are common in the Thar Desert, the researchers wrote, so the stones may have had little to do with the geoglyphs around them. For now, the researchers added, the lines need to be protected; they have already been damaged by vehicles cutting across them since the 2014 satellite images were taken.

The purposes of other geoglyphs around the world remain unexplained, as well. The famed Nazca Lines in Peru depict birds, cats and other animals, and have been studied by modern archaeologists since the 1920s. Nevertheless, no one knows why the lines were made. Circular and hexagonal geoglyphs in the Amazon show no signs of habitation inside, and archaeologists' best guess is that the designs had some sort of ceremonial function. And sometime between the third and fourth millennia B.C. in Russia, geoglyph makers sculpted a giant elk out of rocks. Why? It's yet another earthen mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.