Male lemurs 'stink flirt' using fruity, floral love potion

Scented chemicals lure lemur ladies

Fruity and floral scents help lemur lads lure the ladies, scientists recently learned.

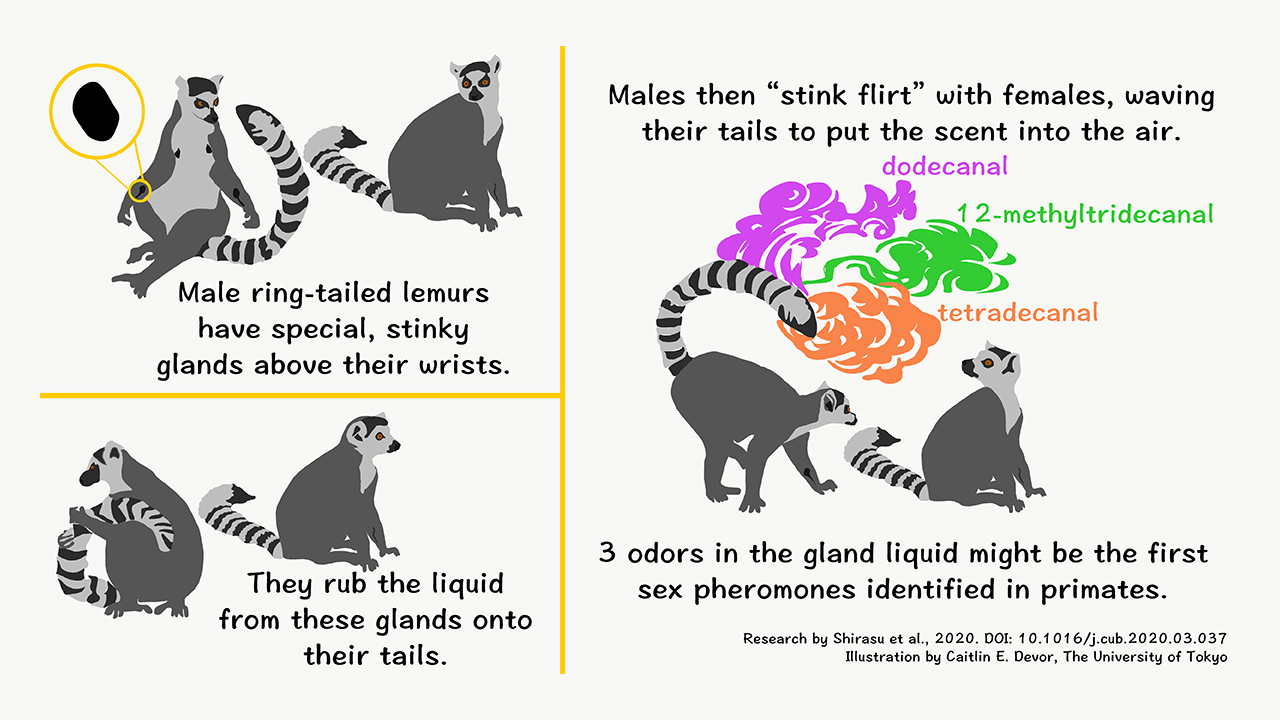

Males produce this smelly secret ingredient in their wrist glands, which they then rub on their tails and waft as a scent cloud toward a likely mate. Secretions from these and other glands are commonly used by male lemurs to communicate with other males — to mark territory, demonstrate their social rank or broadcast their readiness for breeding — but scientists recently discovered that lemurs produce additional chemicals that are used to "stink flirt" with females during their yearly mating season.

This could represent the first evidence of sex pheromones in primates, the group that includes lemurs, great apes and humans, the researchers reported in a new study.

Related: Wild Madagascar: Photos reveal island's amazing lemurs

Female ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) seemed especially interested in the males' wrist secretions during breeding season. This hinted that there might be a chemical component that was present only at this time of year, and that was specifically attractive to females, said co-lead study author Kazushige Touhara, a professor in the Department of Applied Biological Chemistry at the University of Tokyo.

"Most studies of animal communication are done by ecologists," Touhara said in a statement. "What made our study different is that we have expertise in chemistry."

"Fruity, floral and sweet"

The scientists collected samples of wrist secretions from three male lemurs during breeding and nonbreeding seasons. For most of the year, this liquid smelled "bitter," "leathery" and "green" to the human nose, the researchers wrote in the study. But during the breeding season, it smelled "more fruity, floral and sweet." As ring-tailed lemurs are sensitive to olfactory cues, this scent change could signal to females that males are ready to mate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Female lemurs were even attracted to the floral and fruity scent when it was presented to them on a cotton pad, sniffing the breeding season secretions for longer and more avidly than they did with pads that held secretions from other months, the scientists reported.

Chemical analysis revealed three types of odor molecules known as aldehydes that were significantly more abundant in the male lemurs' cologne when breeding season rolled around. The researchers suspected that fluctuations in testosterone might drive these changes; when they boosted testosterone levels in a young male lemur during the nonbreeding season, scent-changing compounds in the animal's wrist glands spiked to levels typically found when males were ready to mate.

"This increase really supports the connection between testosterone and these odor compounds," co-lead study author Mika Shirasu, an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, said in the statement.

While female lemurs were interested in the males' fruity, floral flirtations, it's unclear if this stink flirting makes males more desirable as partners, Touhara said.

"Curiosity does not necessarily mean sexual attraction. We cannot say for certain yet if a female spending a longer time interested in the scent means that a male will be more successful at mating," he explained.

The findings were published online April 16 in the journal Current Biology.

- Double trouble: Lemur twin photos

- Photos of the northern giant mouse lemur

- Secrets of a strange lemur: An aye-aye gallery

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.