Leprosy identified in wild chimpanzees for the first time

The disease was previously unknown in wild non-human primates.

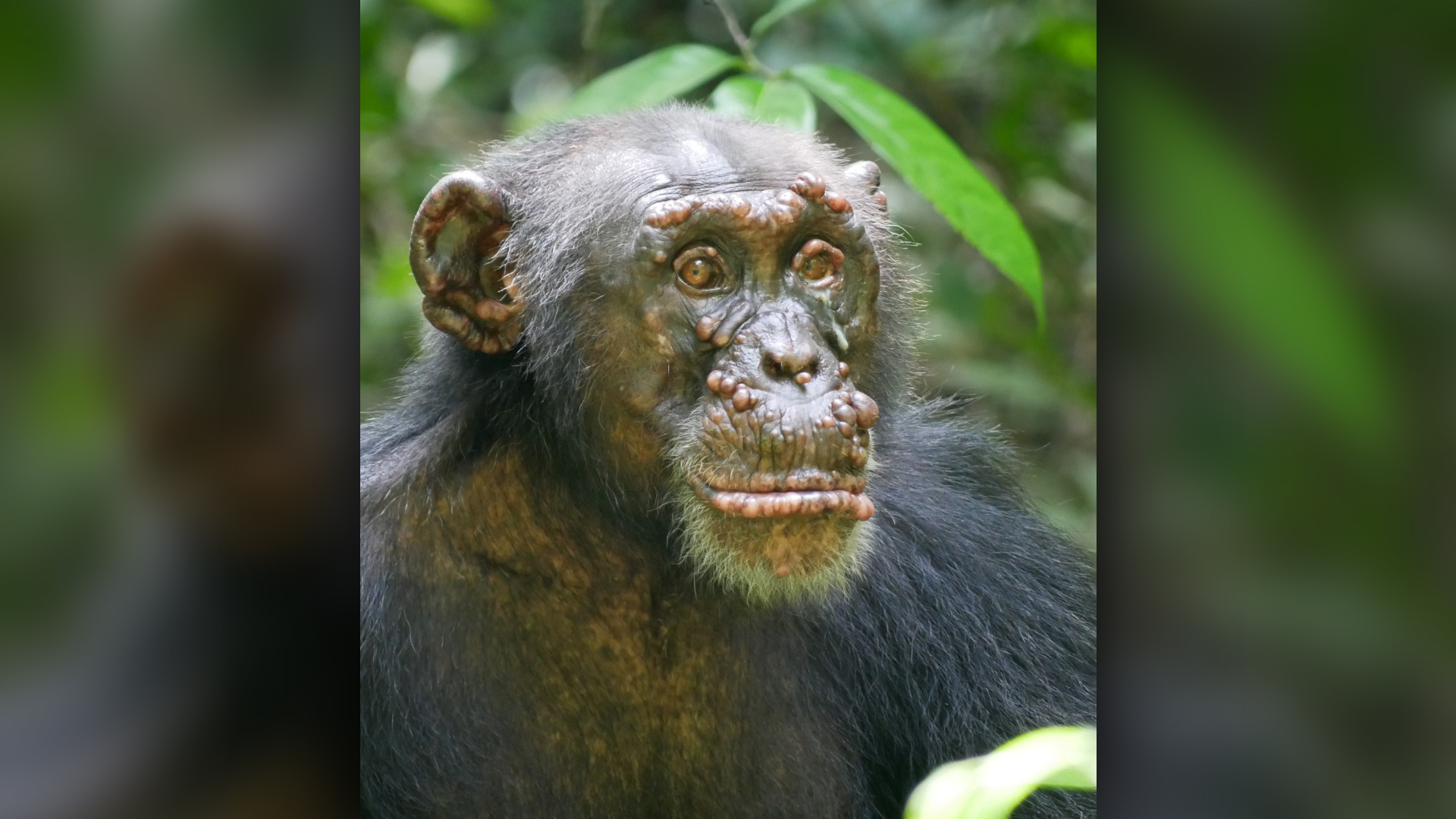

Scientists have detected leprosy in wild chimpanzees for the first time, and the symptoms resemble those in infected people.

A team of researchers recently found leprosy-infected chimps in unconnected populations in two West African countries: Guinea-Bissau and the Ivory Coast. Facial lesions in several of the animals looked like those in humans with advanced leprosy; genetic analysis of the chimps' stool samples confirmed that animals in both groups were carrying Mycobacterium leprae, bacteria that causes the disfiguring disease, according to a new study.

Not only are these cases the first to be detected in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) — leprosy in captive chimps has been reported previously — they are the first known non-human cases of leprosy in Africa.

Related: 6 strange facts about leprosy

Prior to this study, "nothing was known at all about leprosy in wild primates," said lead study author Kimberley Hockings, a senior lecturer in conservation science at the University of Exeter's Centre for Ecology and Conservation in the United Kingdom.

"There were published reports of captive primates, including chimpanzees, with leprosy," Hockings told Live Science in an email. "But the source of infection was unclear, as it is possible that they contracted leprosy whilst in captivity."

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, is an infectious disease that primarily affects people and is caused by the bacteria M. leprae, which scientists identified in the late 19th century, and M. lepromatosis, which was discovered in 2008, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bacteria pass between people in droplets from the nose and mouth during close and frequent contact, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Leprosy symptoms that affect the skin include discolored patches, lesions, ulcers and swelling; other symptoms target the nervous system, resulting in numbness, vision problems and muscle weakness or temporary paralysis, the CDC says. Severe, untreated cases in humans can lead to blindness, permanent paralysis, facial disfigurement and shortening of fingers and toes, but the disease is curable and treatment during the early stages can prevent disability.

Leprosy-causing bacteria multiply slowly and incubate in an infected person for about five years on average, though symptoms can occur within one year or may take 20 years or longer to appear, according to WHO.

Humans are the bacteria's main host, but nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) in the Americas and red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in the U.K. are known reservoirs for leprosy-causing bacteria. While it's unknown how the chimps encountered M. leprae, the new findings suggest that strains of this bacteria may be circulating more widely among wildlife than previously thought, researchers reported Oct. 13 in the journal Nature.

Severe lesions, growths and "claw hand"

The scientists looked at two wild populations of chimpanzees: one in Cantanhez National Park (CNP) in Guinea-Bissau, and one in Taï National Park (TNP) in the Ivory Coast. Camera-trap footage of the CNP chimps recorded from 2015 to 2019 captured 241 images of chimps showing "severe leprosy-like lesions" and growths on their faces, trunks and genitals. Affected chimps also displayed hair loss, facial disfigurement, excessive nail growth and deformed digits, called "claw hand" — another hallmark of leprosy — according to the study. When the scientists analyzed fresh fecal samples, they found DNA evidence suggesting that the chimps were infected with M. leprae.

"We were amazingly able to confirm Mycobacterium leprae in several samples from two female chimpanzees — that are likely mother and daughter — and one of those samples was good enough to run full genome sequencing," Hockings said.

The Ivory Coast chimps, unlike the chimps in Guinea-Bissau, were acclimated to researchers following and observing them in the wild, and biologists noticed in 2018 that one of the animals, an adult male named Woodstock, had leprosy-like lesions on his face that grew bigger and more numerous over the next two years. Fecal sampling and DNA analysis again revealed the presence of M. leprae, as did a necropsy of a female chimp named Zora, who was killed by a leopard in 2009 but began developing lesions approximately two years before her death.

Genetic data showed that the strains of M. leprae affecting the two chimp populations were different. Both were rare strains, not just rare in humans but also in other animal reservoirs, according to the study.

Leprosy is one of the oldest known diseases to be associated with humans — the earliest known case was found in a human skeleton dating to about 4,000 years ago, Live Science previously reported. Consequently, its impacts on infected people have been studied and recorded for centuries. By comparison, next to nothing is known about how chimpanzees have been exposed to the bacteria, how the disease is transmitted between individuals, and how long infected chimps may survive, Hockings said.

"We are only just scratching the surface of leprosy presence and transmission in wildlife," Hockings told Live Science. "I suspect it is much more prevalent than we ever thought."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.