Photos: The beginnings of Maya civilization

San Lorenzo

These lidar images show San Lorenzo (left), an Olmec site that peaked between 1400 B.C. and 1150 B.C.), and Aguada Fénix (right), a Maya site primarily occupied between 1000 B.C. and 800 B.C. Both show a similar pattern of 20 rectangular platforms lining the plaza. In later Maya calendars, 20 was the base unit for counting days, suggesting that this timekeeping system was already in development before 1000 B.C.

Digging up Aguada Fenix

Archaeologist Melina García excavates in the central part of Aguada Fénix. The similarities of this site with the Olmec center of San Lorenzo hints that the Maya and Olmec were interacting intensively 3,000 years ago. They were certainly developing sophisticated building techniques; the site not only includes a large human-made plateau, it's surrounded by human-made reservoirs and a series of causeways and ramps.

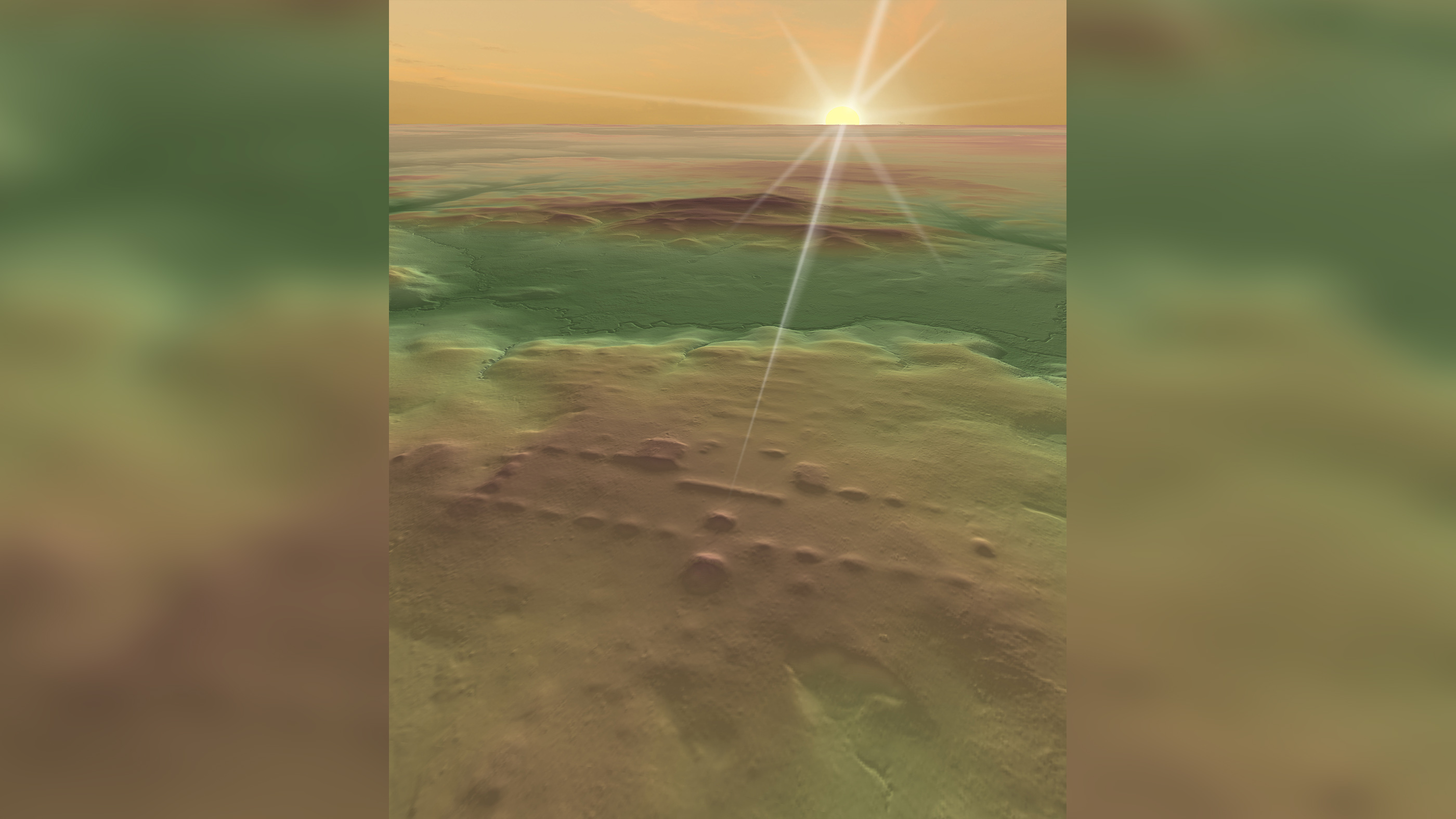

Aligning with the sunrise

Using a remote-sensing technique called lidar to strip away vegetation and visualize topography, University of Arizona archaeologist Takeshi Inomata and his colleagues discovered hundreds of new ancient Olmec and Maya sites in southern Mexico and western Guatemala. This aerial view of Buenavista, a Maya site dating back to about A.D. 300 that had previously been discovered, shows the alignment common to many of these sites: They are laid out to catch the sunrise on certain important days.

El Tiradero

The site of El Tiradero on the San Pedro river. The layout of this site is similar to the famous Classical period Maya site of Ceibal.

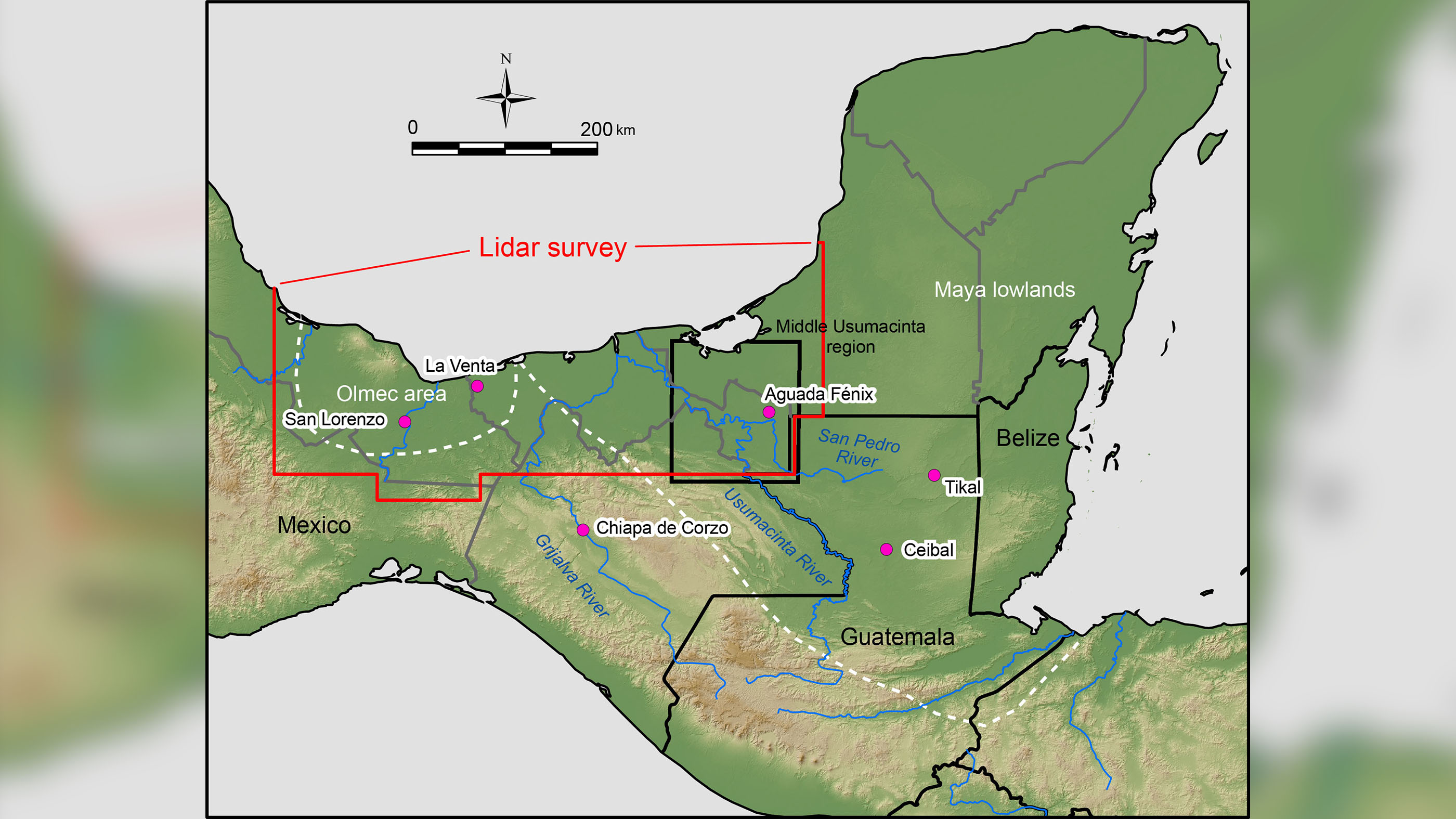

The Olmec and the Maya

A map of the area surveyed by lidar, covering 32,632 square miles (84,516 square kilometers) and showing the position of San Lorenzo in Veracruz and Aguada Fénix in Tabasco.

Aguada Fenix from above

Aguada Fénix is about 0.9 miles (1.4 kilometers) long. It was likely a ceremonial gathering site from the Maya, who are thought to have lived in non-hierarchical, mobile societies at the time they built Aguada Fénix. This is in contrast with the nearby Olmec people, who had a strong social hierarchy and were probably ruled by kings. Nevertheless, both groups seem to have constructed similar population centers around 1000 B.C.

Excavations at Aguada Fenix

Anthropologists Daniela Triadan (left) and Verónica Vázquez (right) excavate at Aguada Fénix. Researchers discovered the site on a cattle ranch in the Mexican state of Tabasco in 2017. An airplane-based lidar survey revealed a platform between 33 and 50 feet (10 to 15 meters) high stretching nearly a mile from north to south.

A hidden past

Researchers hope that excavations at Aguada Fénix and the other newly discovered sites around southern Mexico and western Guatemala will answer questions about the development of civilization in Central America: Did ancient people build complex ceremonial centers without kings or other rulers? Did the Olmec influence the development of Maya culture, or did the Maya largely go it alone?

Hidden architecture

Researchers excavate at La Carmelita, a site in the Middle Usumacinta region of southern Mexico. This site has a similar layout to Aguada Fénix.

Uncovering a city

Archaeologists excavate a trench in Aguada Fénix, a large Maya site in southern Mexico. The site consists of a huge plaza with a long platform to the east, a building to the west and a series of low horizontal mounds.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.