Lost islands beneath the North Sea survived a mega-tsunami 8,000 years ago

Some ancient islands now submerged beneath the North Sea survived a devastating tsunami about 8,000 years ago and may have played a key part in Britain's human prehistory, according to a new study.

The research suggests some parts of the ancient plain known as Doggerland — which connected Great Britain with the Netherlands — withstood the massive Storegga tsunami that submerged most of the region in about 6200 B.C.

The so-called Storegga tsunami was caused by the underwater collapse of part of Norway's continental shelf, about 500 miles (800 kilometers) to the north. Scientists had long thought the towering wave entirely submerged the Doggerland region between the east coast of England and the European continent.

Photos: Ancient human remains found beneath the North Sea

But the new research, based on submerged sediment cores sampled during ship expeditions in the North Sea, suggests some parts of Doggerland survived the ancient tsunami and may have remained inhabited by Stone Age humans for thousands of years.

And if they did, the surviving islands of Doggerland might have played a part in the later development of Britain, such as the introduction of agriculture about a thousand years later said study co-author Vincent Gaffney, an archeologist at the University of Bradford.

"If you were standing on some of that coastline on the day it happened, it would be a bad day for you," Gaffney told Live Science. "However, that did not mean it was the end for Doggerland."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sunken lands

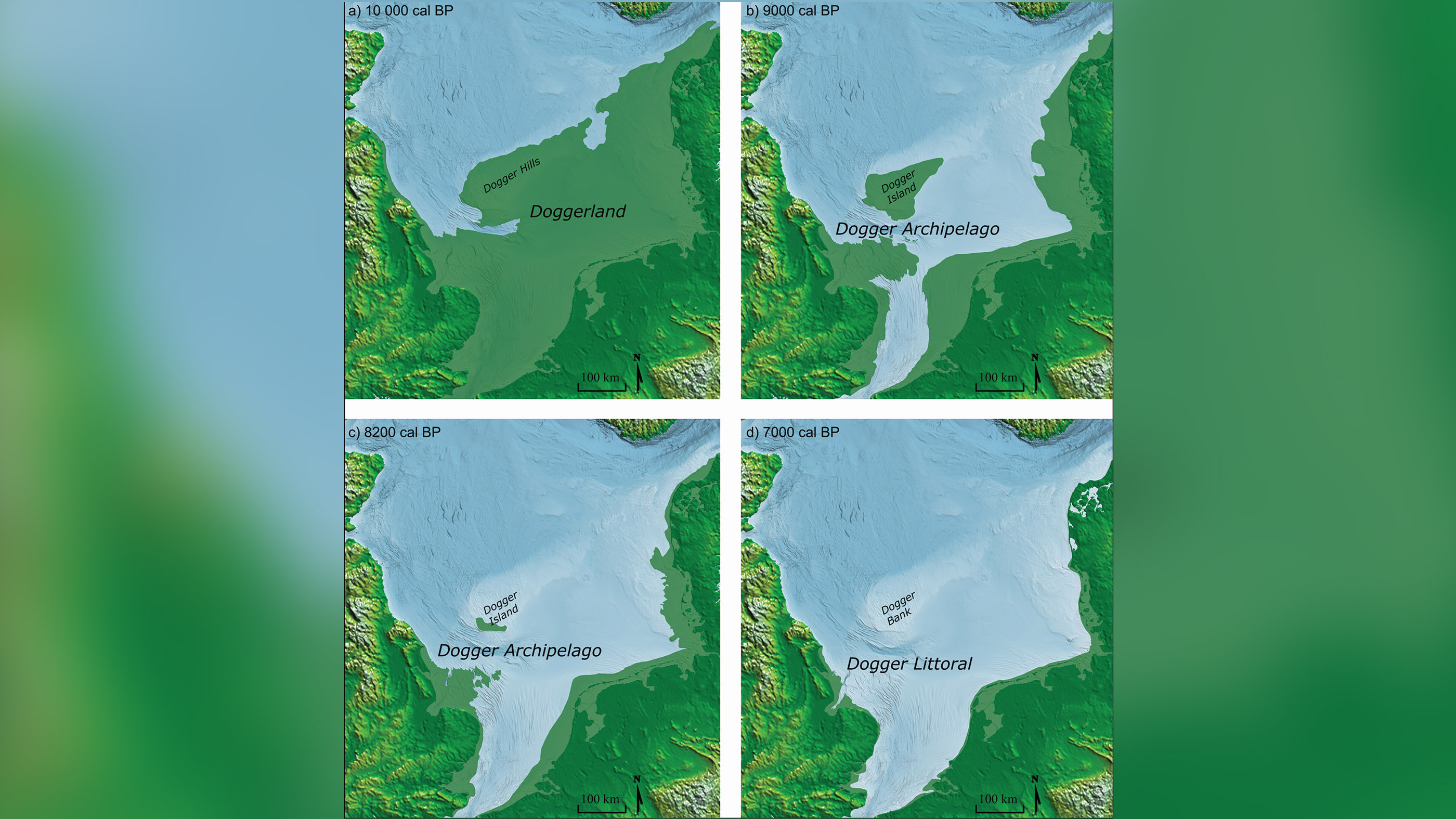

Scientists think the now-submerged region of Doggerland was exposed by the retreating northern ice cap at the end of the last ice age about 12,000 years ago. By about 10,000 years ago, Doggerland was a landscape of lagoons, marshes, rivers, lakes and forests; it may have been one of the richest hunting and fishing grounds in Europe in the Mesolithic period.

The Europe's Lost Frontiers project is leading the effort to investigate Doggerland's archaeology and to reconstruct the ancient landscape as it appeared before it sank beneath the waves.

They found that by the time of the Storegga tsunami, much of Doggerland would have been already underwater due to slowly rising sea levels, Gaffney said.

But a remarkable sediment core from the seafloor near the eastern English estuary of the River Ouse, known as the Wash, shows land there remained above water many years after the tsunami — and computer modeling suggests other regions nearby survived as isolated islands too, he said.

The researchers have now dubbed these islands the "Dogger Archipelago," and it's thought the highest parts of a central region now known as the "DoggerHills" also survived the Storegga tsunami, becoming "Dogger Island."

Although they initially stayed dry land, the islands would all sink a bit more than 1000 years later as the sea level rose, caused by the warming climate.

Surviving islands

Some parts of Doggerland may even have been better suited to humans after the devastation of the tsunami and the retreat of its waters, Gaffney said.

"People will have gone back and lived where they were previously, and it may have perhaps been a bit more open, and that may even have been quite useful in some of these areas," he said.

The surviving islands may contain early evidence of the introduction of agricultural technologies into Britain, which presumably spread there from the European continent, he said. "It is these coastal areas which are where contact with farming and farmers are likely to occur."

For now, the researchers on the Europe's Lost Frontiers project are working to reconstruct the ancient geography of the Doggerland region.

One day, they hope to locate a Stone Age settlement, and the now-submerged islands of the Dogger Archipelago are emerging as some of their best bets.

"The last 20 years has revolutionized how we understand Doggerland," Gaffney said. "We have been going down [submerged] river valleys to get environmental data, where we can get information on the plants and animals that lived there."

[But] we do not have yet a single archaeological settlement site," he said. "It's still essentially an unexplored landscape."

The research was published Monday (Nov. 30) in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.