Lost Version of '50 Shades' of Medieval Erotica Is Rediscovered

An early version of a raunchy medieval manuscript was being used as a book binding.

Researchers have discovered a long-lost version of a medieval romance "novel" containing a sex scene too steamy for even modern publishers.

The French poem, "Le Roman de la Rose" (The Romance of the Rose), tells the story of a courtier wooing a woman — the poems titular "rose." It was the "Twilight" of its day, a crowd-pleasing romance that was reproduced again and again.

"'Le Roman de la Rose' really was the blockbuster of its day," Marianne Ailes, a medievalist at the University of Bristol in the U.K. who identified the new fragments of the manuscript, said in a statement. "We know how popular it was from the number of surviving manuscripts and fragments, a picture our fragment adds to, and from the number of allusions to the text in other medieval writings."

Related: Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts

Too hot for publication

Every version of the 22,000-line romance is slightly different, Ailes said, and the version portrayed in these fragments is no exception. They contain a scene left out of modern printings of the poem, one that is more "Fifty Shades of Grey" than "Twilight." In the scene, the narrator uses an extended metaphor of a pilgrim presenting himself before a religious reliquary to insinuate a sexual encounter. He describes his walking stick, or staff, as "stiff and strong," and speaks of "sticking it into those ditches." If the point wasn't clear, he also describes himself as kneeling in front of the relic "full of agility and vigour, between the two fair pillars...consumed with desire to worship."

The innuendo has been raising eyebrows for centuries. In 1900, medievalist F.S. Ellis left the raunchy section in its original French, refusing to translate it to English. Explaining this choice, he wrote that he "believes that those who will read them will allow that he is justified in leaving them in the obscurity of the original."

Related: The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in History

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The standard modern edition of the poem produced by French publisher Livre de Poche also leaves out some of these lines, Ailes said in the statement.

Hot-and-heavy history

"Le Roman de la Rose" was written by two authors and completed in 1280. The new fragments were found in the archives of the Diocese of Worcester, discovered in the Worcester Record Office by Nicholas Vincent from the University of East Anglia.

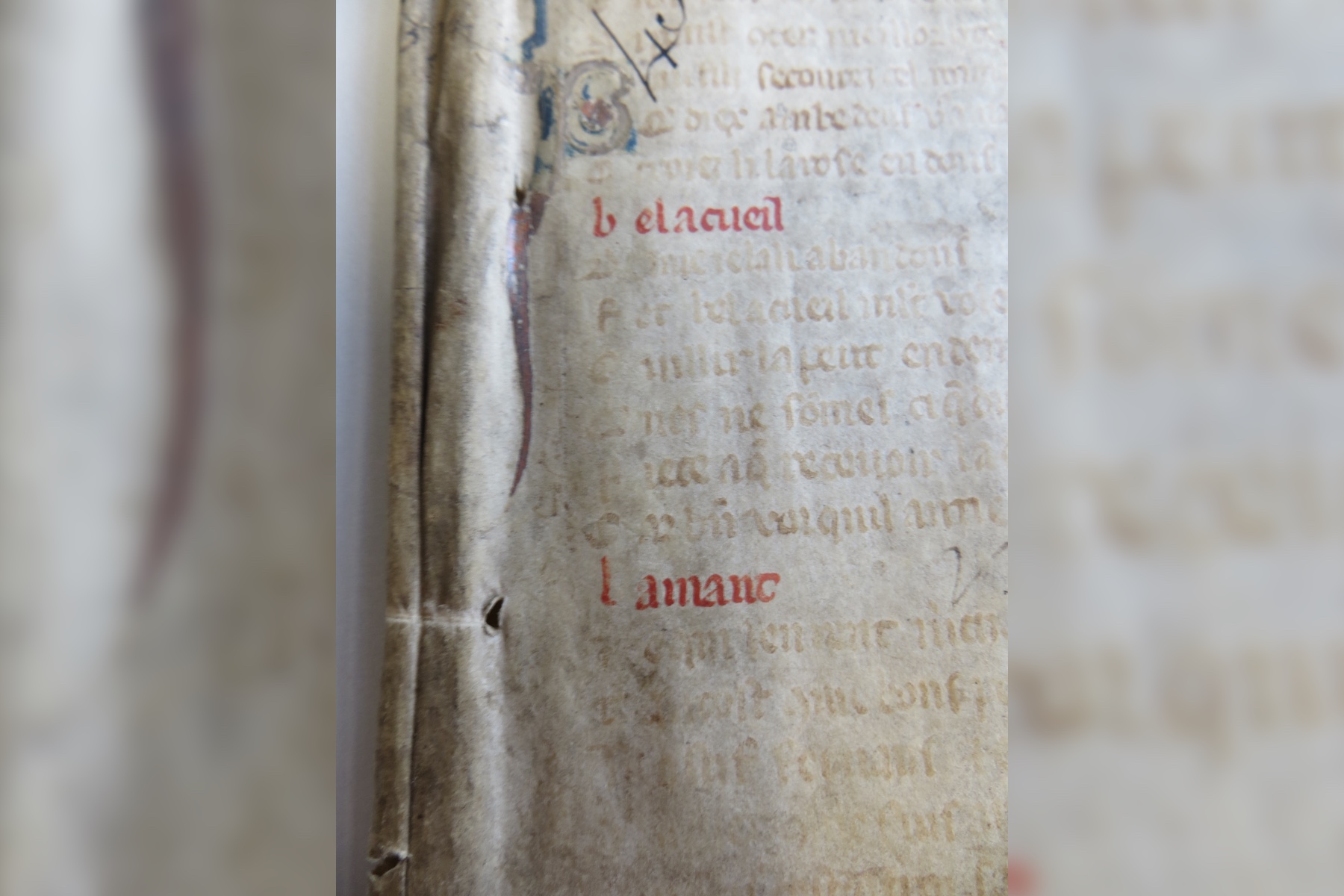

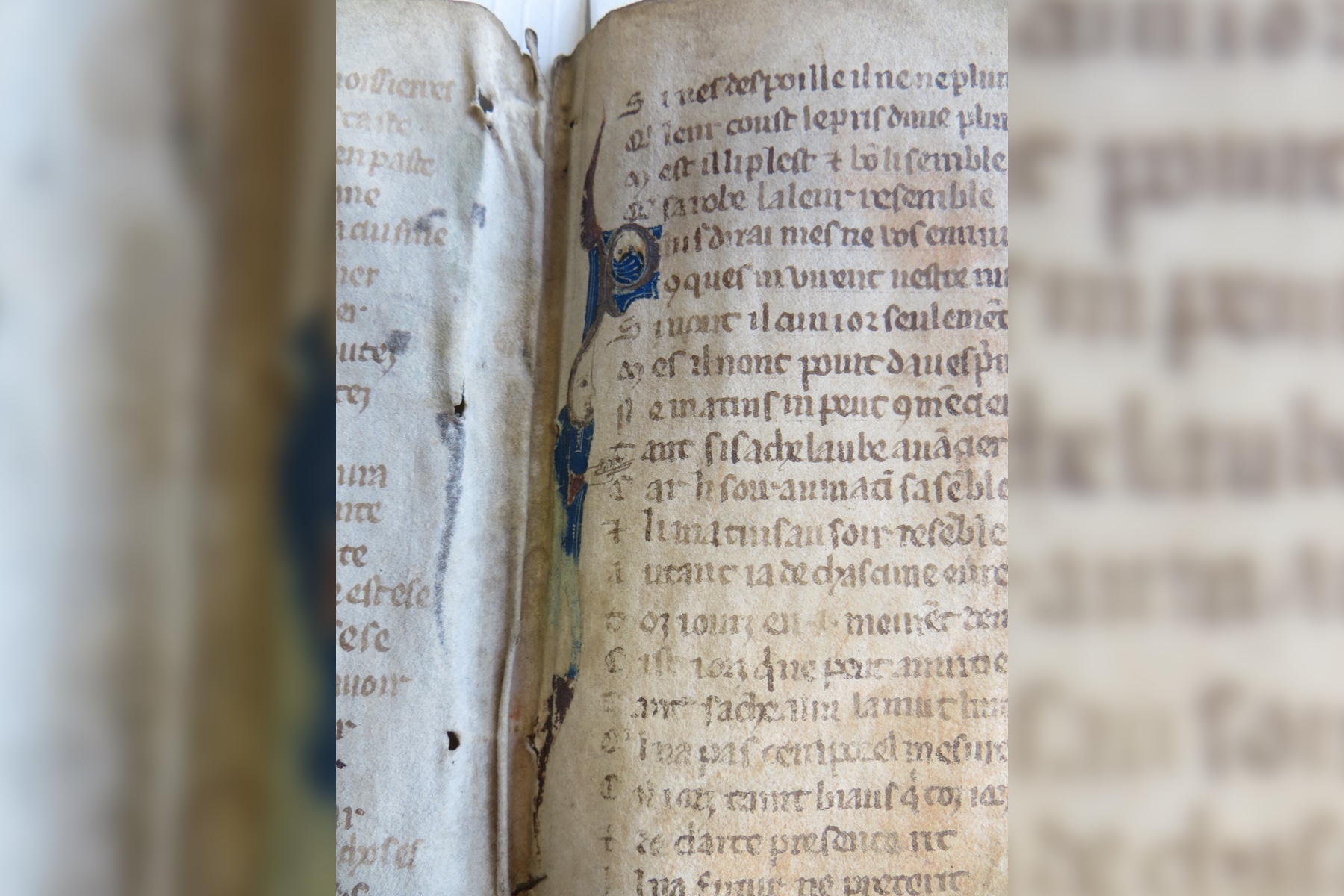

The handwritten parchment papers were being used as a book binding for some other papers, Ailes said, and it was immediately clear that they were something special. First, the handwriting on the recycled binding looked much older than the papers within. Second, Ailes noticed a famous phrase from "La Roman de la Rose" — "bel accueil." This translates to "fair welcome."

"'The Roman de la Rose' was at the center of a late medieval row between intellectuals about the status of women, so we have the possibility that these specific pages were taken out of their original bindings and recycled by someone who was offended by these scenes," Ailes said.

Geoffrey Chaucer, the bawdy English poet best known for "The Canterbury Tales," completed a partial translation of "The Romance of the Rose" about a century after the poem was first written.

"No two copies of a text in [a] manuscript are ever identical so each new find adds another piece to a jigsaw, which helps us understand how these texts were read and re-interpreted in the Middle Ages," Ailes said.

- 12 Bizarre Medieval Trends

- What Was It Like to Be an Executioner in the Middle Ages?

- Photos: 33 Stunning Locations Where 'Game of Thrones' Was Filmed

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality