This Australian bird's cry sounds just like a human baby

His name is Echo.

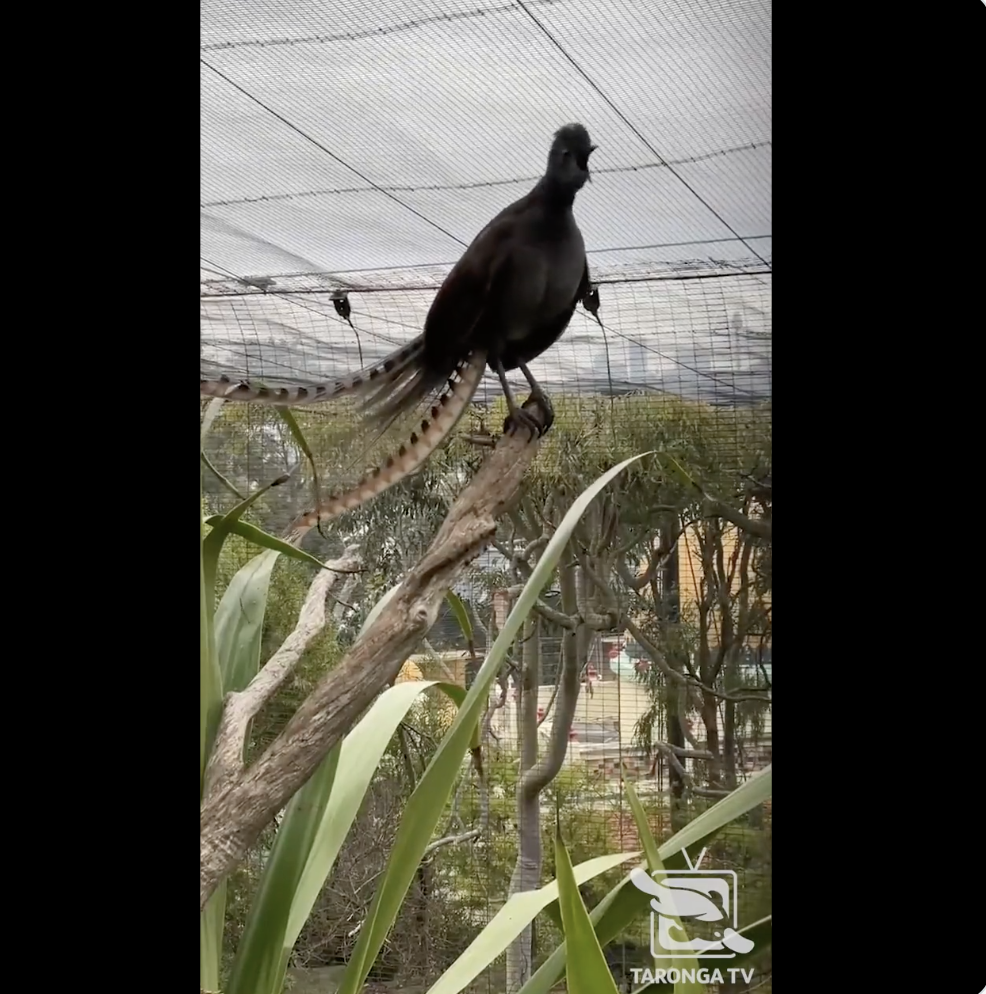

The wails coming from an enclosure at Taronga Zoo Sydney in Australia may sound like the cries of a human baby. But don't be alarmed. It's just a trickster resident: A brown, long-tailed bird named Echo has learned how to mimic the shrieks and shrills of human babies.

Taronga Zoo Sydney posted a video of the impressive bird on Twitter on Aug. 30. "Bet you weren't expecting this wake-up call," the zoo tweeted. "You're not hearing things, our resident lyrebird Echo has the AMAZING ability to replicate a variety of calls - including a baby's cry."

Echo is a superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), an Australian bird named for the shape of its tail during courting, according to Britannica. The tail looks like an instrument known as a lyre — a U-shaped stringed instrument that was popular in ancient Greece.

Related: 10 amazing things you didn't know about animals

Lyrebirds are experts at mimicry; they can copy just about any sound in their immediate surroundings, including those from chainsaws and car engines, as well as animal sounds, such as dog barks and bird calls, according to the Australian Museum.

Bet you weren't expecting this wake-up call! You're not hearing things, our resident lyrebird Echo has the AMAZING ability to replicate a variety of calls - including a baby's cry! 📽️ via keeper Sam #forthewild #tarongatv #animalantics pic.twitter.com/RyU4XpABosAugust 30, 2021

Seven-year-old Echo holds true to his name; he can mimic the sound of a power drill, a fire alarm and the "evacuate now" announcement at the zoo, Leanne Golebiowski, the unit supervisor of birds at Taronga Zoo Sydney, told The Guardian.

About a year ago, Echo started practicing snippets of baby cries, she said. But it's not clear how he perfected the calls, as the zoo is closed to visitors because of COVID-19 lockdowns in Sydney. "I can only assume that he picked it up from our guests," Glebiowski said. "Obviously he has been working on his craft during lockdown. But this concerns me, as I thought the zoo was a happy place for families to visit!"

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Male lyrebirds use their mimicking talents mainly for courtship, according to the National Audubon Society. During their breeding season, from June to August, male lyrebirds can be heard singing for up to 4 hours a day. Their songs consist of a conglomeration of different bird calls that they have picked up from their surroundings. But sometimes, their mating songs incorporate other, nonbird sounds.

Famed naturalist David Attenborough, in his 1998 series "The Life of Birds," presented a lyrebird that was mimicking the sounds of a camera, a car alarm and foresters using chain saws. (You can watch the snippet here.)

Lyrebirds' impressive talents make them talented con artists. Recently, Cornell University researchers found that superb lyrebirds can mimic the sounds of not only other birds but also groups of birds that have flocked together as if in danger from a nearby predator, according to a Cornell statement about the findings of a study published Feb. 25 in the journal Current Biology.

"The male superb lyrebird creates a remarkable acoustic illusion," lead author Anastasia Dalziell, now at the University of Wollongong in Australia, said in the statement. The male lyrebirds only do this during mating or when the female breaks off the courtship, according to the study. The point is likely to create the illusion that there's danger elsewhere and that the female should stay with him, according to the statement.

Female lyrebirds also have the ability to mimic sounds, but they likely do it for other reasons, such as defense, according to The Guardian.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.