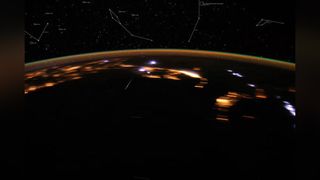

The Lyrids are about to peak. Here's how to watch.

Meteor season 2022 is kicking off.

The Lyrid meteor shower peaks this week, offering a possible opportunity to see a dozen or so meteors an hour streaking across the night sky.

The Lyrids occur each year when Earth's orbit takes it through the long trail of debris left in the orbit of Comet Thatcher. The shower will reach its maximum at 4 a.m. Coordinated Universal Time (12 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time) on Friday, April 22, according to the American Meteor Society (AMS). The best viewing may come a night or two after the peak, though, as the moon will be on the wane. It's the first chance to see a significant number of meteors since the Quadrantid shower ended in January.

"People talk about this as being like the first robin of spring, the first meteor shower of the year," Ka Chun Yu, the curator of space science at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, told Live Science.

How to see the Lyrids

This year's Lyrid peak is happening when the moon is 67% full, making a good view of the meteors a bit challenging. In ideal viewing conditions, the Lyrids typically produce a maximum of about 18 meteors an hour, but the actual rate depends on the amount of light pollution and the viewer's position relative to the radiant, or the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to emanate. The Lyrids are best observed from the Northern Hemisphere, where the radiant point near the bright star Vega is well above the horizon. Meteors can be visible from the Southern Hemisphere as well, though.

The best time to look for Lyrids this year, according to EarthSky, is about an hour before midnight local time, when Vega will be above the horizon toward the northeast and the moon will not yet be too high in the sky. It's not crucial to look at the radiant; in fact, longer-tailed meteors are often most visible farther from the radiant, Yu said. Meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. The rules of thumb for best viewing? Get away from light pollution as much as possible, give your eyes 30 minutes to adjust, and lay flat on your back looking upward to take in as much sky as possible.

Given the moonlit nature of the night on April 22, it might also help to get into the shadow of a tree or dark building, according to EarthSky.

What causes the Lyrids?

The reason for the Lyrids, Comet Thatcher, was discovered in 1861. The comet takes 415.5 years to orbit the sun and has been at it awhile: The first recorded sighting of the Lyrids dates back to 687 B.C. in China, according to NASA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The comet itself is currently on a long sojourn in the far reaches of the solar system. According to EarthSky, it's currently 107 times as far away as the distance between Earth and the sun, still headed outbound in its long orbit. It will return to the interior of the solar system in 2278.

The bits of dust and debris that burn up to create the Lyrid light show are only about the size of grains of sand, Yu said, but they're traveling at up to 31 miles per second (50 kilometers per second) relative to Earth, explaining the massive friction that causes them to burst into flame in the atmosphere.

Every 60 years, the Lyrids produce outbursts, or meteors showering through Earth's atmosphere at a rate of up to 100 per hour. An outburst that dramatic is unlikely this year, as the next outburst year is predicted to be 2042, according to EarthSky. These outbursts are predictable because they're caused by the gravitational impact of the planets on the comet's debris trail, Yu said.

"When they all tend to be roughly aligned, it can cause the orbit of this debris to shift so Earth will basically intersect it right in the center of the trail as opposed to right toward the edges," Yu said.

The Lyrids end on April 29. The next promising meteor shower for the Northern Hemisphere will be the alpha Capricornids, which peak on the night of July 30. The alpha Capricornids rarely produce more than about five meteors an hour, but do tend to produce bright fireballs, according to the AMS. Casual skywatchers may want to hold out for the Perseids, however, which are active from July 14 to Sept. 1 this year and can produce 50 to 75 visible meteors an hour.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.