Secret words exchanged between Marie Antoinette and rumored lover uncovered in redacted letters

"Beloved," "madly" and "tender friend" are among the censored words scientists recently uncovered in the series of secret letters.

"Beloved," "madly" and "tender friend" are among the censored words scientists recently uncovered in a series of secret letters Marie Antoinette exchanged with her close friend — and rumored lover — Swedish count Axel von Fersen.

Von Fersen and Antoinette, queen of France and wife of King Louis XVI, exchanged a handful of secretive letters over the span of a year in the late 18th century, during the French Revolution. By the time historians got their hands on some of the letters that von Fersen had saved, which were purchased from the Fersen family archive and are now kept in the French Archives, someone had marked out certain words and phrases.

Now, a group of French researchers has uncovered passionate language in the censored phrases in eight of 15 letters exchanged between the two. An analysis of the ink suggests that von Fersen himself censored Antoinette's letters and drafts of his own, according to the findings, published Oct. 1 in the journal Science Advances

Related: Did Marie Antoinette really say 'Let them eat cake'?

The authors were careful not to make drastic conclusions about Antoinette and von Fersen's rumored romantic relationship, though a relationship is "quite obvious," said lead author Anne Michelin, a researcher at the Conservation Research Center in France.

But "the letters are only one aspect of this relationship," and the feelings that they express in their writings may have been intensified by the crisis around them, Michelin told Live Science in an email.

Behind the ink

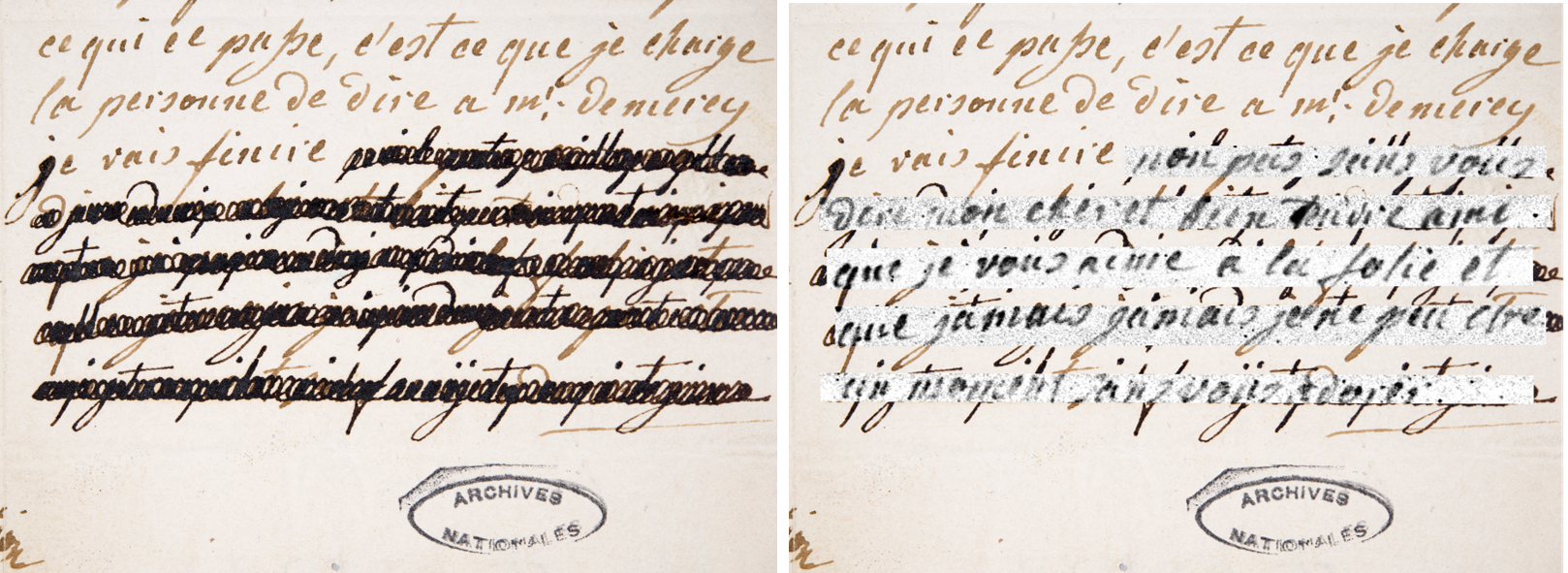

To uncover the writing behind the redactions — tight swirls of dark scribbles complicated by the addition of extra letters to throw off the reader — the researchers used a method called X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The XRF scanner directs X-rays onto the image, exciting the atoms that are present in the ink, which then emit unique wavelengths that allow researchers to identify which atoms are present in each pixel. They can then create a series of images in which the pixels are only filled in if a certain wavelength — corresponding with a specific element — is present.

Imagine that you wrote the word "love" in an ink that's made up solely of copper and then you scribbled over it with an ink that's made up solely of iron. If you scanned this piece of redacted writing for iron, the program would output a bunch of scribbles; but if you scanned it for copper, the word "love" would appear.

Of course, that's a highly simplified example and the ink used in the letters and the redactions are made up of a combination of elements. In the letters, the researchers looked for differences in the ratios of copper to iron and zinc to iron.

They found that some of the redactions were just words such as "amour" or "love," and some of them were phrases such as "ma tendre amie," or "my tender friend." Some were even longer, such as "pour le bonheur de tous trois" which translates to "for the happiness of all three" and "non pas sans vous," which translates to "not without you."

Their method did not work in recovering the censored writing in seven of the documents because both inks had very similar composition, making it "impossible" to read the underlying words, the authors wrote. Curators and historians are now supervising the transcription of the full paragraphs that were revealed.

"A fantastic job...I think the images speak for themselves," said Joris Dik, a professor and head of the Materials Science and Engineering department at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. Dik and his colleagues at Antwerp University were the first to develop the XRF spectroscopy technique about 10 years ago, to scan for hidden images in large surfaces such as paintings.

Who did it?

Next, the researchers tried to identify the scribbler. The main hypothesis in the field was that the censor was likely someone in von Ferson's family — perhaps to preserve their reputation — such as his great-nephew.

But when the researchers further analyzed the ink of the redactions, they came upon a different story.

With handwriting analysis, they first discovered that many of the letters that were supposedly written by Antoinette were actually copies of her letters written by von Fersen. Copying letters was common practice at the time for record-keeping, but he could have also copied them for political reasons. If Antoinette's letters had been encrypted, von Fersen may have copied them as he decoded them. "In times of crisis, for their security, it is sometimes necessary that the authors of the letters cannot be identified," Michelin said.

They compared the composition of those inks used by von Fersen with the redaction inks and found that the composition of the redaction ink was the same as the writing ink in another letter.

Related: How many French revolutions were there?

"The coincidence was too big," Michelin said. What's more, in one letter, von Fersen added a few words — a specialist confirmed it was his handwriting — above a redacted passage in the same ink as the redaction. The redacted text read "the letter of the 28th reached me," whereas the initial text was "the letter of the 28th made my happiness."

It's not clear why von Fersen would have chosen to redact and keep these letters rather than get rid of them. "Perhaps this correspondence was important to him for sentimental reasons or for political strategies," Michelin said. We can imagine that he wanted to keep the correspondence about the political situation — numerous passages in the letters are about this — perhaps to be able to show it to people from foreign royal courts to defend Marrie Antoinette's position, she added.

If von Fersen is indeed the censor, and used the same ink, "this would explain why the last letters could not be read," the authors wrote. The composition of the redaction ink and the composition of the ink in the letters written by von Fersen seem to be the same from December 1791 to May 1792, which is why those redactions were unreadable. Their method works, both Michelin and Dik noted, only if the compositions of the two inks are different.

So while "it is not a robust solution that solves all cases," this study makes massive progress in the field of analyzing redacted texts, said Matthias Alfeld, an assistant professor for X-rays in Art and Archaeology also in the materials science and engineering department at the Delft University of Technology, who was not part of the study. The authors employed a reasonable approach, got trustworthy results and overall, it's very good work, he told Live Science in an email.

Now, Michelin and her team hope to use artificial intelligence to help them decipher some of the poorer quality texts that they uncovered underneath the redactions.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.