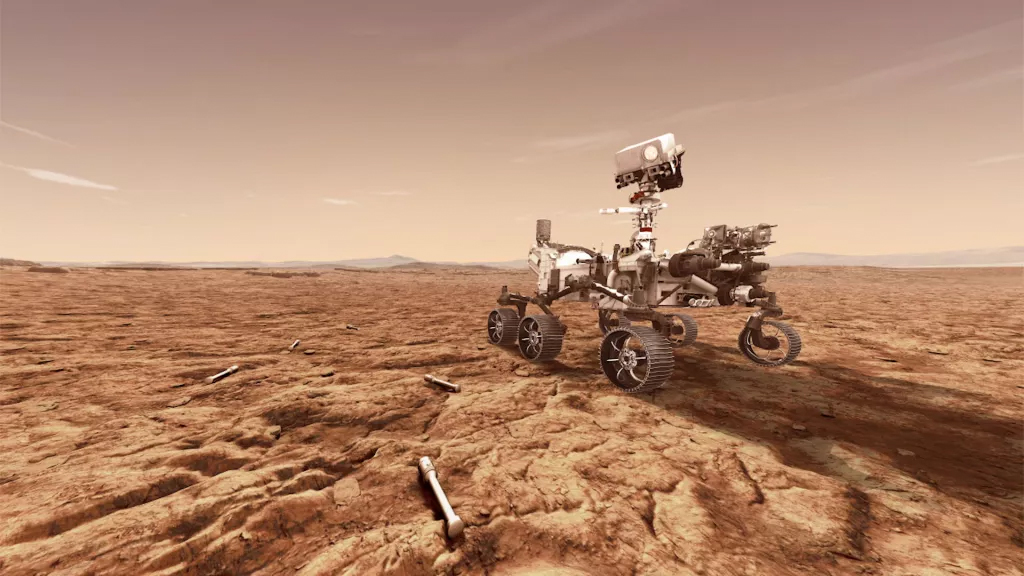

Having safely landed on Mars on Feb. 18, NASA's newest rover, Perseverance, is just beginning its scientific exploration of the Red Planet. But sometime in the next few weeks, the car-size robot will also help pave the way for future humans to travel to our neighboring world with a small instrument known as the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE).

MOXIE, which will soon be pulling precious oxygen out of Mars' poisonous atmosphere, is gold-colored and about the size of a bread box. It sits tucked away inside Perseverance's chassis, where it will conduct the first demonstration on another planet of what's known as in-situ resource utilization (ISRU), meaning using local resources for exploration rather than bringing all the necessary materials from Earth.

NASA has long been interested in ISRU and put out a call for an oxygen-producing experiment when Perseverance was first being conceived, Eric Daniel Hinterman, an aerospace engineering doctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and member of the MOXIE team, told Live Science.

Related: New Way to Make Oxygen Doesn't Need Plants

While oxygen is useful for astronauts to breathe, Hinterman said that it's even more important as rocket propellant. When combined with hydrogen, oxygen combusts in a powerful explosion that is used to lift many modern rockets from their launch pads.

In addition to the propellant needed to get off Earth and fly to Mars, a spacecraft bringing humans to the Red Planet would need between 66,000 and 100,000 pounds (30,000 and 45,000 kilograms) of oxygen to return home, according to NASA. "We can send that oxygen from Earth to Mars, but if we can make it on the surface that potentially saves us a lot of money," Hinterman said.

Any additional oxygen produced through ISRU technology could go into life-support systems for astronauts while on the surface of Mars, Hinterman said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In order to reach the ground, Perseverance had to go through a complicated sky crane maneuver and the famous "seven minutes of terror" that subjected all of its components to some fairly extreme forces. A few days after landing, the MOXIE team put the instrument through a series of what are known as "aliveness" tests to make sure it was in working order.

"We had it turn on and send some data [to confirm] that it survived," Hinterman said. "When we got the data, we popped some champagne and celebrated."

Though MOXIE's first oxygen-producing run hasn't been scheduled yet, it is expected to happen sometime in the rover's first months on the Red Planet. The instrument uses a technology called solid oxygen electrolysis, Hinterman said.

This process involves taking in a small sample of the Martian atmosphere, which is almost entirely carbon dioxide, a molecule containing one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms. MOXIE will heat the air up to nearly 1500 degrees Fahrenheit (800 degrees Celsius) and apply a voltage across it. That should split the carbon dioxide apart, producing carbon monoxide and a single oxygen atom.

MOXIE won't be storing any of the oxygen it produces, simply verifying that the element was successfully made and then releasing it back to the atmosphere, said Hinterman. It's only a small prototype about 200 times smaller than a similar machine that would be used on a future human mission, he added.

The experiment will run many times over the course of a Martian year — "on a hot summer's day, on a cold winter's night, and during a global or local dust storm," Hinterman said — to ensure that it can work under a wide variety of conditions.

That's because a scaled-up version of MOXIE would be critical infrastructure on an eventual human mission. Though the technology works on Earth, "to really be confident in something that humans will rely on for survival, it's important to test that technology on Mars," said Hinterman.

He is excited to be part of a project that is helping to demonstrate something important for human Mars exploration and is confident that such a mission will happen in the coming decades. "I'm dedicating my career to getting humans to Mars," he said. "If we don't have humans on Mars within my lifetime, I'll take it personally."

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.