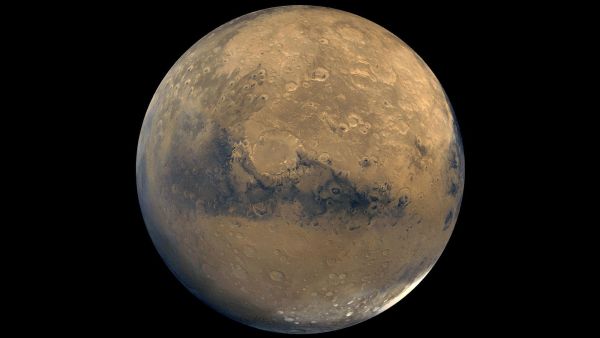

Mars may hide oceans of water beneath its crust, study finds

The might not have been lost to space after all.

Oceans' worth of water may remain buried in the crust of Mars, and not lost to space as previously long thought, a new study finds.

Prior work found Mars was once wet enough to cover its entire surface with an ocean of water about 330 to 4,920 feet (100 to 1,500 meters) deep, containing about half as much water as Earth's Atlantic Ocean, NASA said in a statement. Since there is life virtually everywhere on Earth where there is water, this history of water on Mars raises the possibility that Mars was once home to life — and might host it still.

However, Mars is now cold and dry. Previously, scientists thought that after the Red Planet lost its protective magnetic field, solar radiation and the solar wind stripped it of much of its air and water. The amount of water Mars still possesses in its atmosphere and ice would only cover it with a global layer of water about 65 to 130 feet (20 to 40 m) thick.

Related: Mars may be wetter than we thought (but still not that habitable)

But recent findings suggest Mars could not have lost all of its water to space. Data from NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN) mission and the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter revealed that at the rate water disappears from the Red Planet's atmosphere, Mars would have lost a global ocean of water only about 10 to 82 feet (3 to 25 m) deep over the course of 4.5 billion years.

Now scientists find that much of the water Mars once had may remain hidden in the crust of the Red Planet, locked away in the crystal structures of rocks beneath the Martian surface. They detailed their findings online March 16 in the journal Science and at the Lunar Planetary Science Conference.

Using data from rovers on and spacecraft orbiting Mars, as well as meteorites from Mars, the researchers developed a model of the Red Planet estimating how much water it started with and how much it might have lost over time. Potential mechanisms behind this loss included water escaping into space, as well as getting incorporated chemically into minerals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One way scientists estimate how much water Mars lost to space involves analyzing hydrogen levels within its atmosphere and rocks. Every hydrogen atom contains one proton within its nucleus, but some possess an extra neutron, forming an isotope known as deuterium. Regular hydrogen escapes from a planet's gravity more easily than heavier deuterium.

By comparing levels of lighter hydrogen and heavier deuterium atoms in Martian samples, researchers can estimate how much regular hydrogen the Red Planet might have lost over time. Since each water molecule is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, these estimates of Martian hydrogen loss therefore reflect how much Martian water has disappeared, as solar radiation broke water on Mars apart into hydrogen and oxygen molecules.

In the new study, the scientists found chemical reactions may have led between 30% to 99% of the water that Mars initially had to get locked into minerals and buried in the planet's crust. Any remaining water was then lost to space, explaining the hydrogen-to-deuterium ratios seen on Mars.

All in all, the researchers suggested Mars lost 40% to 95% of its water during its Noachian period about 4.1 billion to 3.7 billion years ago. Their model suggested the amount of water on the Red Planet reached its current levels by about 3 billion years ago.

"Mars basically became the dry, arid planet we know today 3 billion years ago," study lead author Eva Scheller, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com.

The new estimates of the amount of water buried in the Martian crust range widely because of the uncertainty over the rate at which Mars lost water to space in the distant past, Scheller noted. She explained that NASA's Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in February, can help refine these estimates, "as it is going to one of the most ancient parts of the Martian crust, and so can help us nail down the past process of water loss to the crust much better."

Although much of the water that Mars had may still be locked away within its crust, that does not mean any future astronauts to the Red Planet will find it easy to extract that water to help them live there, Scheller cautioned.

"All in all, there still isn't a lot of water in the Martian crust, so you would have to heat a lot of rocks to get an appreciable amount of water," Scheller said.

Originally published on Space.com.