Mary, Queen of Scots' rosary beads stolen in English castle heist

The ill-fated royal carried the beads to her execution.

The prayer beads of infamous 16th-century ruler Mary, Queen of Scots have been stolen in a daring heist from Arundel Castle in England. The beads and other stolen items are worth around $1.4 million (1 million British pounds), but their historical importance is "priceless," according to a castle spokesperson.

Thieves broke into the castle, in West Sussex, on May 20, less than a week after the site reopened to the public after being closed during most of the COVID-19 pandemic. Police think the burglars entered through a castle window, smashed the glass cabinet displaying the artifacts and made off with the contents before security could respond to the alarm. The thieves likely used a 4x4 as the getaway vehicle and then set it on fire and abandoned it nearby, according to the BBC.

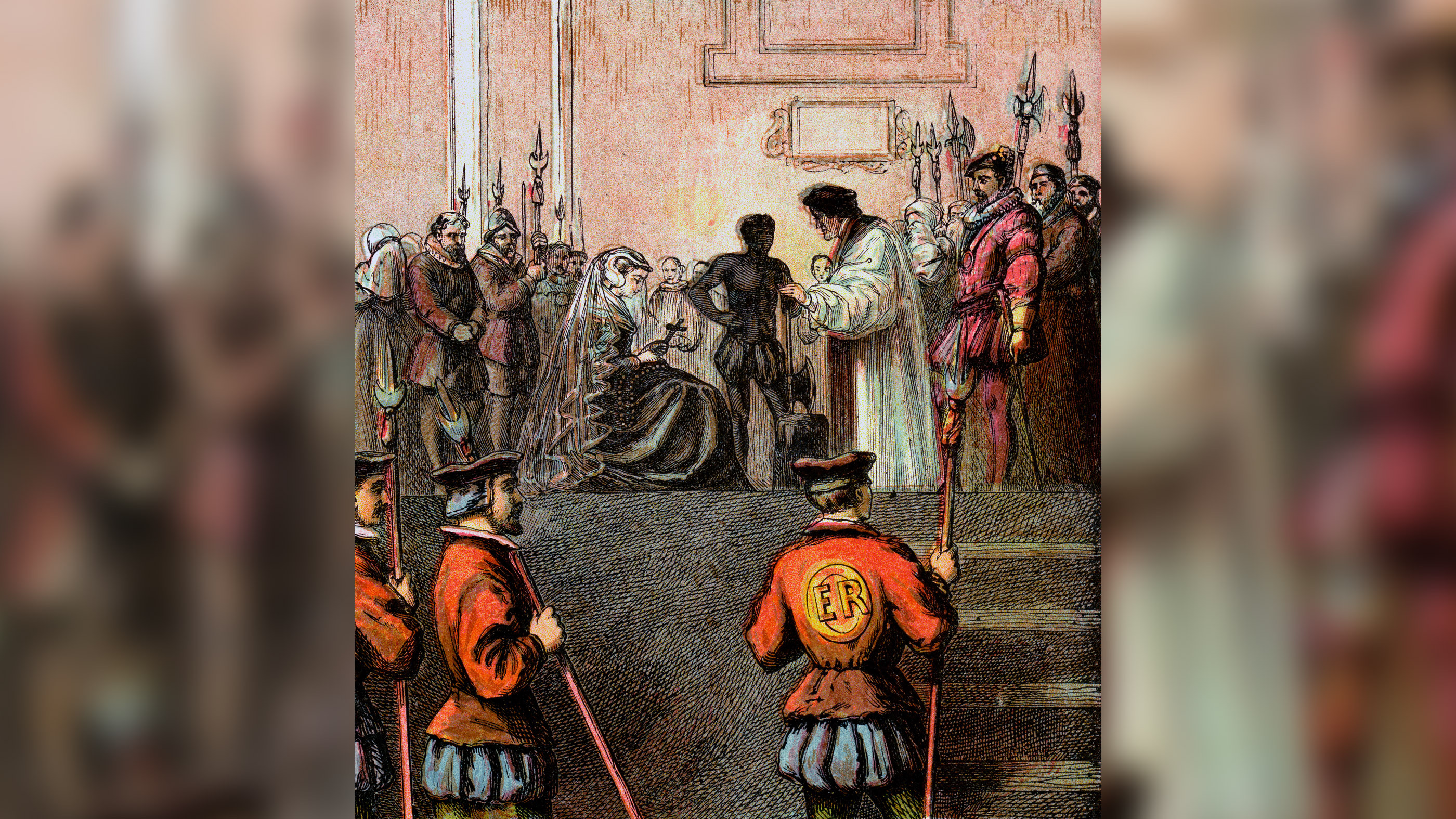

Mary, Queen of Scots, who briefly ruled Scotland and was considered by some to be the rightful heir to the English throne, reportedly carried the ornate set of gold rosary beads during her 18-year imprisonment at the hands of her paranoid cousin Elizabeth I, queen of England, and even held them during her execution in 1587, according to the BBC.

Related: 30 of the world's most valuable treasures that are still missing

"The rosary is of little intrinsic value as metal," an Arundel Castle spokesperson told the BBC, "but as a piece of the nation's heritage, it is irreplaceable."

The thieves also stole a set of coronation cups that Mary gave to the Earl Marshal, a royal title currently held by the owner of all the stolen artifacts, Duke of Norfolk Edward William Fitzalan-Howard.

Police are asking anyone with information regarding the robbery to come forward.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Who was Mary, Queen of Scots?

Mary was born in 1542 and was the only child of King James V of Scotland, who died just six days after she was born, leaving the country to be governed by regents. At age 5, Mary was sent to France, the homeland of her mother, where she grew up in the court of King Henry II and eventually married his son Francis, who ascended the French throne in 1559. That made Mary the queen consort of France. However, Francis died prematurely just a year later, leaving Mary a widow at the age of 18, according to Britannica.

Mary returned to Scotland in 1561 to take her crown as queen of Scotland but was unpopular among the Scottish nobility. During her absence, Scotland had transitioned from Roman Catholic to Protestant, and many saw the openly Catholic and France-raised queen as a foreigner. After six years and two poorly chosen marriages by Mary, the first of which led to the birth of her son James, the Scottish nobility revolted and she was forced to flee to England to take refuge with her cousin Elizabeth I, the queen of England, according to Britannica.

Elizabeth resented Mary because she was next in line for the English throne, as well as being queen of Scotland, with some nobles even considering her to be the rightful queen. Elizabeth, therefore, had Mary tried and convicted of murdering her second husband, Henry Stewart, a crime that has never been proved by historians despite tensions between the couple at the time. Mary spent the next 18 years imprisoned at various English castles before being executed in 1587 at the age of 44. Her son James I later ascended the English throne after Elizabeth died without an heir, according to Britannica.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.