Massive, 1.2 million-year-old tool workshop in Ethiopia made by 'clever' group of unknown human relatives

An unknown group of hominins crafted more than 500 obsidian hand axes more than 1.2 million years ago in what is now Ethiopia.

More than 1.2 million years ago, an unknown group of human relatives may have created sharp hand axes from volcanic glass in a "stone-tool workshop" in what is now Ethiopia, a new study finds.

This discovery suggests that ancient human relatives may have regularly manufactured stone artifacts in a methodical way more than a half-million years earlier than the previous record, which dates to about 500,000 years ago in France and England.

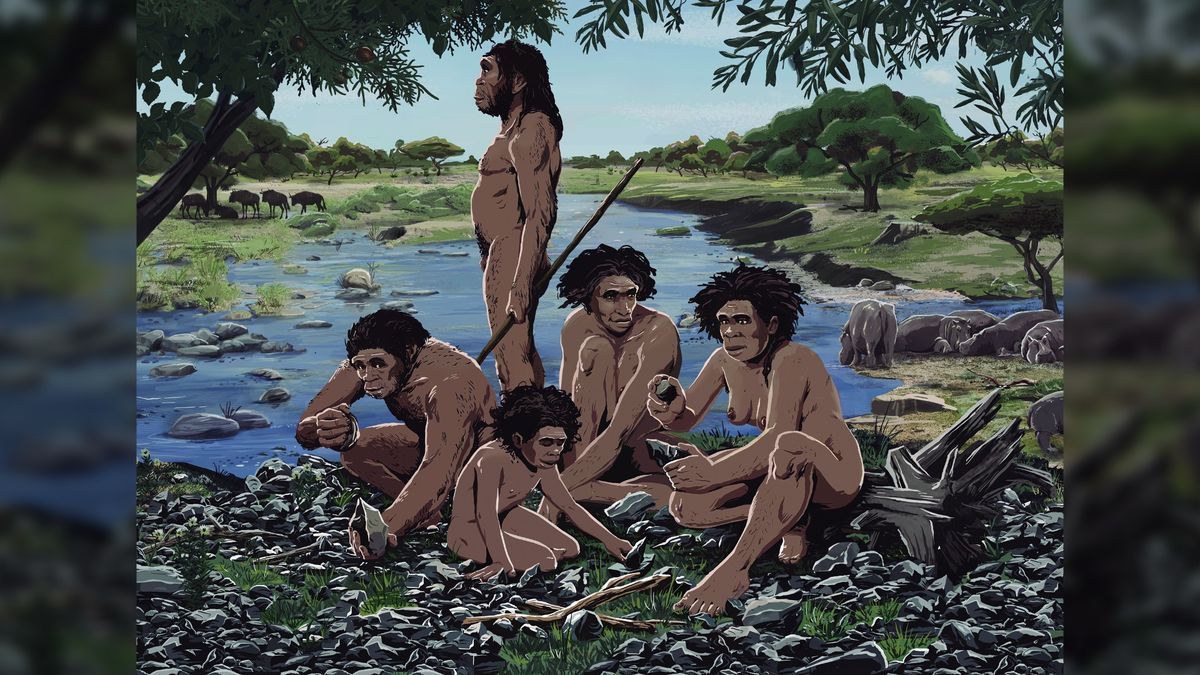

Because it requires skill and knowledge, stone tool use among early hominins, the group that includes humans and the extinct species more closely related to humans than any other animal, can offer a window into the evolution of the human mind. A key advance in stone tool creation was the emergence of so-called workshops. At these sites, archaeologists can see evidence of hominins methodically and repeatedly crafting stone artifacts.

The newly analyzed trove of obsidian tools may be the oldest stone-tool workshop run by hominins on record. "This is very new in human evolution," study first author Margherita Mussi, an archaeologist at the Sapienza University of Rome and director of the Italo-Spanish archeological mission at Melka Kunture and Balchit, a World Heritage site in Ethiopia, told Live Science.

Oldest known hominin workshop

In the new study, the researchers investigated a cluster of sites known as Melka Kunture, located along the upper Awash River valley of Ethiopia. The Awash valley has yielded some of the best known examples of early hominin fossils, such as the famous ancient relative of humanity dubbed "Lucy."

The scientists focused on 575 artifacts made of obsidian at a site known as Simbiro III in Melka Kunture. These ancient tools came from a layer of sand dubbed Level C, which fossil and geological data suggest is more than 1.2 million years old.

These obsidian artifacts included more than 30 hand axes, or teardrop-shaped stone tools, averaging about 4.5 inches (11.5 centimeters) long and 0.7 pounds (0.3 kilograms). Ancient humans and other hominins may have used them for chopping, scraping, butchering and digging.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Obsidian proved far more rare at Simbiro III before and after Level C, and scarce in other Melka Kunture sites. The new excavations also revealed that Level C experienced seasonal flooding, with a meandering river likely depositing obsidian rocks at the site during this time of Level C. Obsidian axes from this level were far more regular in shape and size, which suggests mastery of the manufacturing technique.

Ancient hominins "are very often depicted as barely surviving, struggling with a hostile and changing environment," Mussi said in an email from the field in Melka Kunture. "Here we prove instead that they were clever individuals, who did not miss the opportunity of testing any resource they discovered."

This nearly exclusive use of obsidian at Level C of Simbiro III is unusual during the Early Stone Age, which ranged from about 3.3 million to 300,000 years ago, the researchers said. Obsidian tools can possess extraordinarily sharp cutting edges, but the volcanic glass is brittle and difficult to craft without smashing. As such, obsidian generally only found extensive use in stone tool manufacture beginning from the Middle Stone Age, which ranged from about 300,000 to 50,000 years ago, they said.

"The idea that ancient hominins of this era valued and made special use of obsidian as a material makes a lot of sense," John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who did not take part in this research, told Live Science. "Obsidian is widely recognized as uniquely valuable among natural materials for flaking sharp-edged tools; it is also highly special in appearance. Some historic cultures have used obsidian and traded it across distances of hundreds of miles."

That trading may have gone on farther back than widely acknowledged.

"There has been evidence since the 1970s that obsidian may have been transported across long distances as early as 1.4 million years ago," Hawks said. "That evidence has not been replicated by more recent excavation work, but the new report by Mussi and coworkers may be a step in that direction."

It remains uncertain which hominin may have created these artifacts. Previously, at other Melka Kunture sites, researchers have discovered hominin remains about 1.66 million years old that may have been Homo erectus, and fossils about 1 million years old that may have been Homo heidelbergensis, Mussi said. H. erectus is the oldest known early human to possess body proportions similar to modern humans, whereas H. heidelbergensis may have been a common ancestor of both modern humans and Neanderthals, according to the Smithsonian. Since the age of Level C at Simbiro III is more than 1.2 million years old, the hominins that made the obsidian hand axes there may have been closer in nature to H. erectus, Mussi said.

The scientists detailed their findings Jan. 19 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.