Hiker finds bombs dropped into Mauna Loa volcano in 1935

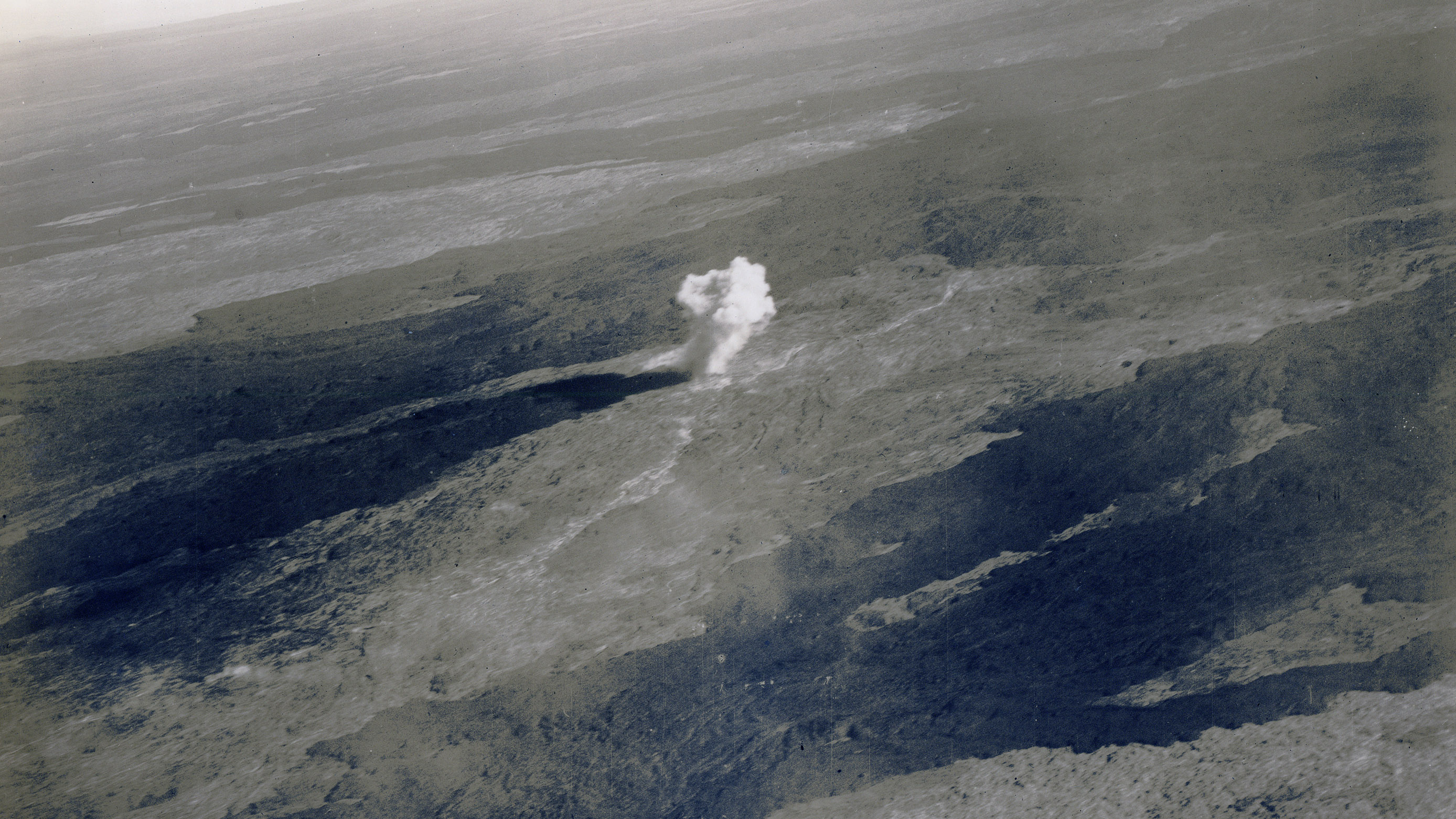

The Army Corps tried to blast the source of a huge lava flow at the time.

In late February, a hiker on Hawaii's Big Island stumbled across two unexploded bombs on the flank of the Mauna Loa volcano. Those bombs, it turns out, were the remnants of a 1935 attempt to divert a lava flow.

Whether the "bomb the volcano" strategy worked is a matter of some debate, according to a new blog post by the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO). The lava flow did begin to slow the next day, and the man whose idea the bombing was claimed victory. Scientists at the time and today, though, believe the slowing flow was almost certainly a coincidence.

The two rusty bombs were found by adventurer Kawika Singson, who was hiking on Mauna Loa's lava fields on Feb. 16 and stumbled across the bombs inside a lava tube, according to West Hawaii Today. Hawaii has a history of trying to bomb lava flows, according to the newspaper: The strategy was tried in 1935 and 1942.

Related: The 10 greatest explosions ever

The bombs Singson found, though, were from the 1935 attempt, according to HVO. They are small "pointer bombs," which contain only a small charge and were used for aiming and targeting a set of 20 MK I demolition bombs, each of which contained 355 pounds (161 kilograms) of TNT.

The idea to drop bombs on Mauna Loa came from the founder of HVO, volcanologist Thomas A. Jaggar, Jr. In November 1935, Mauna Loa began erupting, and a vent on the volcano's north flank belched lava into a growing pond. That December, the pond breached, sending a flow of lava toward the city of Hilo at a rate of 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) per day. Soon, the lava threatened to spill into the Wailuku River, which could cut off Hilo's water supply.

Alarmed, Jaggar called in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He hoped that dropping bombs near the source of the flow would open up new flows at the lava vents, diverting the river of molten rock away from Wailuku.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our purpose was not to stop the lava flow, but to start it all over again at the source so that it will take a new course," he said in a radio broadcast at the time, according to HVO.

That didn't happen. The bombs fell on Dec. 27, but did not create any new eruptive activity on the vents. However, the lava flow did slow, and the vent's eruption halted by Jan. 2. Jagger called it a success, saying that the lava flow would not have stopped so quickly had the bombs not been dropped. In 1939, after the eruption had ended, he visited the bombing sites and claimed that the bombs had smashed into lava tunnels, exposing eruptive lava to air and cooling it. This, he said, created a dam of cooling lava that plugged the vent.

Notably, this wasn't what Jagger had expected to happen; he thought the bombs would trigger new lava flows in different directions, not plug the vent altogether. And a 1970s investigation suggested that his interpretation of how well the bombing had worked was wishful thinking.

"Ground examination of the bombing site showed no evidence that the bombing had increased viscosity, and … the cessation of the 1935 flow soon after the bombing must be considered a coincidence," the investigators concluded.

Today, HVO scientists think Jagger's bombing happened as the lava flow was already waning. There may be times when diversion could work, they wrote in 2014, but the effort involved is Herculean and may only delay the inevitable, should nature decide to take its course.

- The 10 Most Hazardous Countries for Volcanoes (Photos)

- Photos: Hawaii's New Underwater Volcano

- In Photos: Aftermath of Iceland Volcano Floods

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.