Giant pyramid built by the Maya was made from rock spewed by a volcano

The enormous structure may have been intended to honor the eruption.

About 1,500 years ago, Maya builders crafted a massive pyramid out of rock that had been ejected by a volcano, in an eruption that was so powerful it chilled the planet, scientists recently discovered.

Around A.D. 539, in what is now San Andrés, El Salvador, the Ilopango caldera erupted in what was the biggest volcanic event in Central America in the last 10,000 years. Known as the Tierra Blanca Joven (TBJ) eruption, the volcano produced lava flows that extended for dozens of miles, and it belched so much ash into the atmosphere over Central America that the climate cooled across the Northern Hemisphere, researchers previously reported.

Because of the volcano's destructive power, scientists thought that many of the region's Mayan settlements were abandoned, possibly for centuries. But in a recent analysis of a Mayan pyramid known as the Campana structure, Akira Ichikawa, a Mesoamerican archaeologist and postdoctoral associate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder (UCB), found that people returned to the region much sooner, building the monument just decades after the eruption.

Related: In photos: Hidden Maya civilization

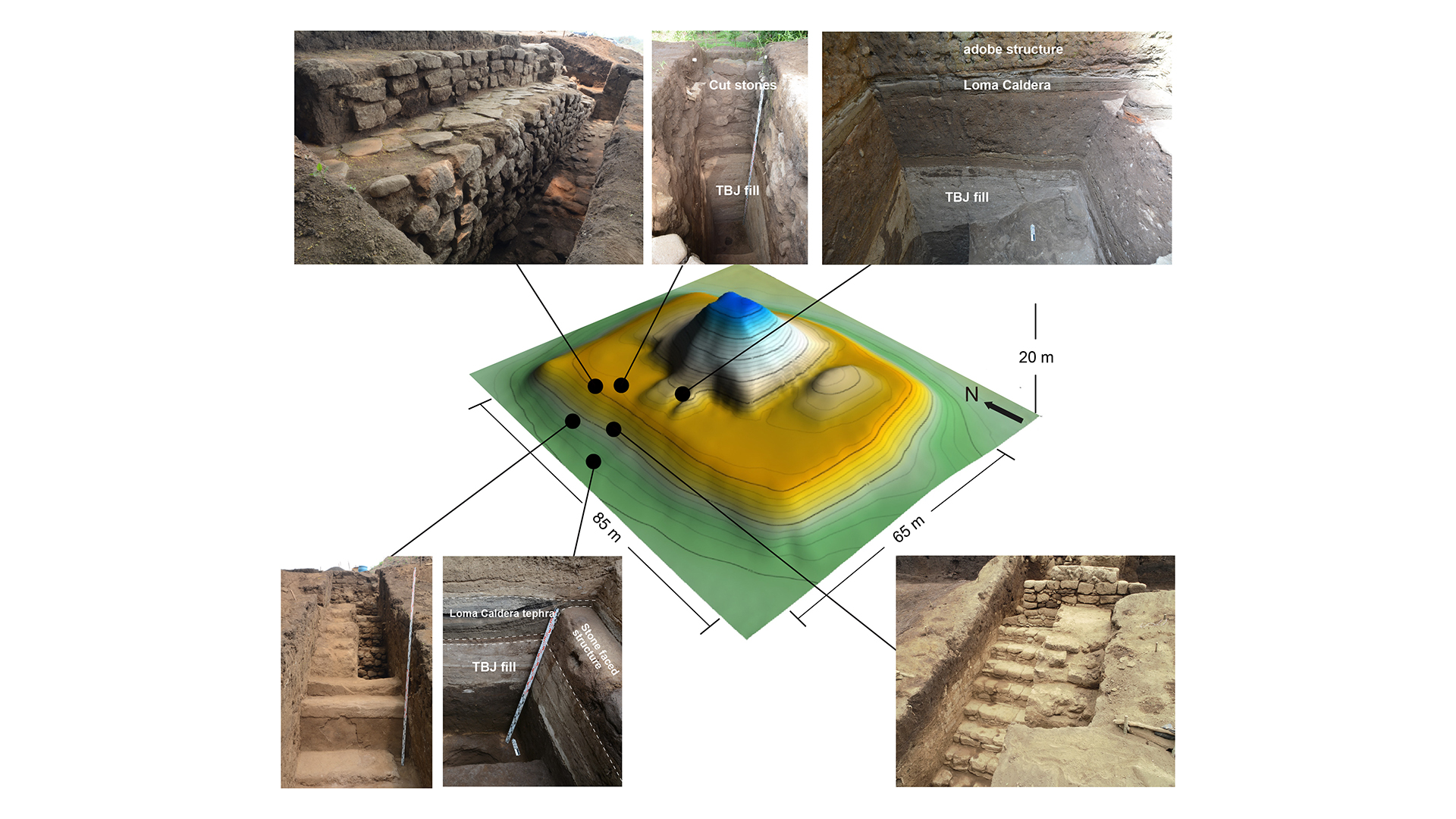

New analysis of the pyramid, located about 25 miles (40 kilometers) from the volcano in the Zapotitán Valley, also revealed that Maya builders mixed cut stone blocks and earth with blocks carved from tephra — rock ejected by a volcano. This is the first evidence that volcanic ejecta was used in the construction of a Mayan pyramid, and it could reflect the spiritual significance of volcanoes in Mayan culture, Ichikawa said.

Scholars have debated the date of the TBJ eruption for decades, with some arguing that the volcano erupted much earlier, between A.D. 270 and A.D. 400, Ichikawa wrote in the new study, published Sept. 21 in the journal Antiquity. However, recent radiocarbon dating (comparing ratios of radioactive carbon isotopes) in tree trunks from El Salvador had hinted that A.D. 539 was a more accurate estimate, Ichikawa said.

The Campana pyramid rests atop a platform that measures nearly 20 feet (6 meters) high, 262 feet (80 m) long and 180 feet (55 m) wide, and the pyramid itself stands about 43 feet (13 m) tall. The platform also includes four terraces and a broad central staircase. It was the first public building erected in the valley's San Andrés site after the TBJ eruption, which would have buried much of the valley under nearly 2 feet (0.5 m) of ash, according to the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ichikawa calculated the age of the structure using carbon samples taken from different building materials in the pyramid, dating them to between A.D. 545 and A.D. 570. This suggested that people returned to the site and began construction on the pyramid far sooner than expected, possibly within five years of the TBJ eruption, Ichikawa said.

The quantity of tephra in the pyramid was also surprising, he told Live Science in an email. About a decade ago, UCB archaeologist and professor Payson Sheets detected tephra in a Mayan "sacbe" or "white road" — an elevated thoroughfare — at the site Joya de Cerén. Also located in El Salvador, Cerén's pre-Hispanic farming community was buried in a volcanic eruption around A.D. 600 and is known as the "Pompeii of the Americas," Ichikawa explained.

However, Campana is the first known Mayan monument to include tephra as a construction material. In Cerén's sacbe, white-ash tephra "may have been perceived to have powerful religious or cosmological significance" because of its volcanic origin, and tephra may have held similar importance in the Campana pyramid, according to the study.

Climate and environmental disasters, such as volcanic eruptions, are often linked to the collapse or decline of ancient civilizations; in Ptolemaic Egypt (305 B.C. to 30 B.C.), a volcano may have doomed an ancient dynasty, and when an Alaskan volcano erupted in 43 B.C., it may have spelled the end of the Roman Republic, Live Science previously reported. But the Campana structure tells a different story, demonstrating that ancient people were capable of rebuilding from the ashes of destruction, and that they were more resilient, flexible and innovative than previously suspected, Ichikawa said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.