Never-before-seen volcanic magma chamber discovered deep under Mediterranean, near Santorini

Using a technique to study seismic waves, researchers revealed a previously unknown magma chamber underneath a the Kolumbo submarine volcano.

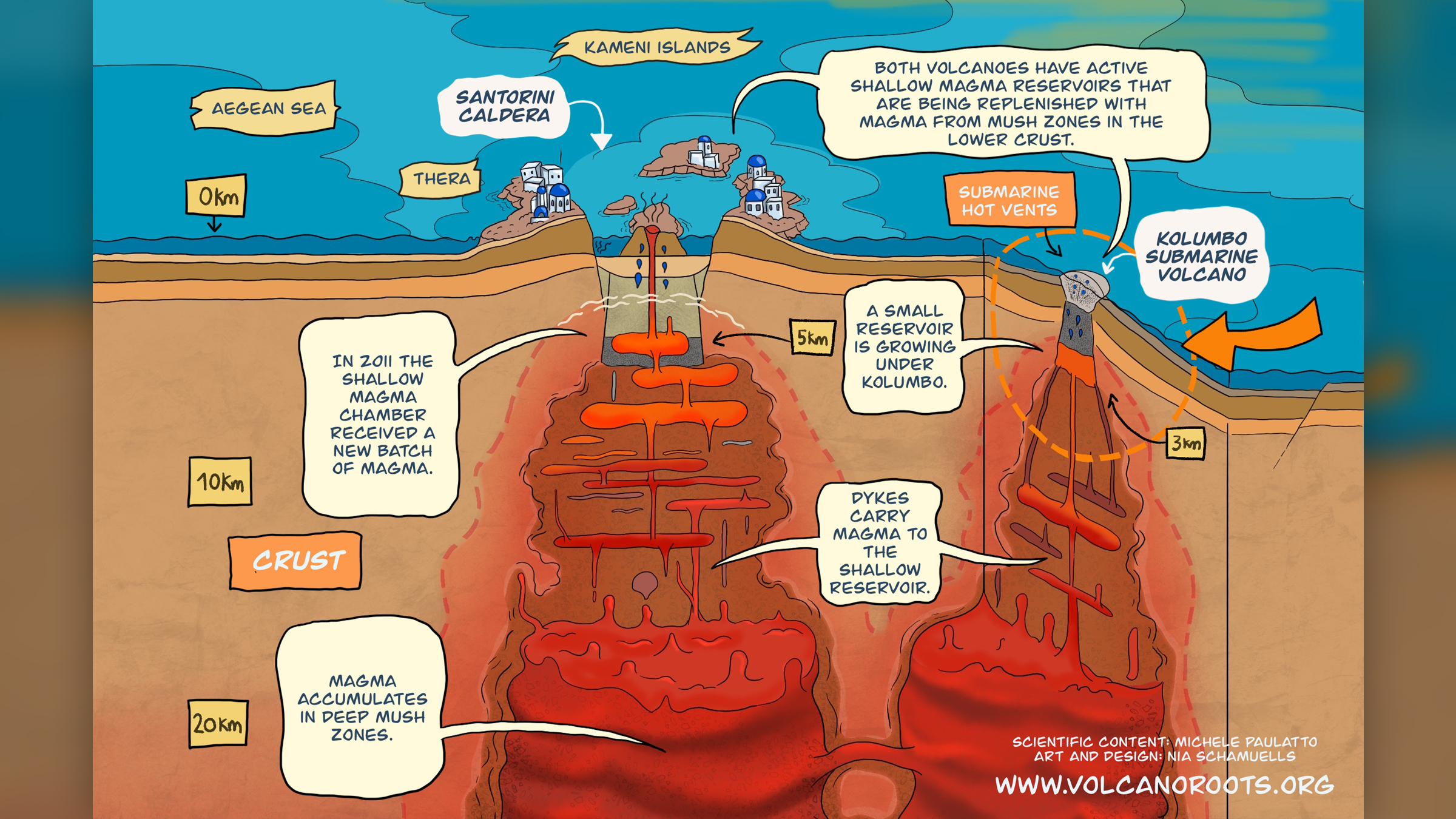

A submarine volcano whose deadly eruption shattered the picturesque Greek island of Santorini nearly 400 years ago has a growing, never-before-seen magma chamber that could fuel another massive eruption within the next 150 years, a new study finds.

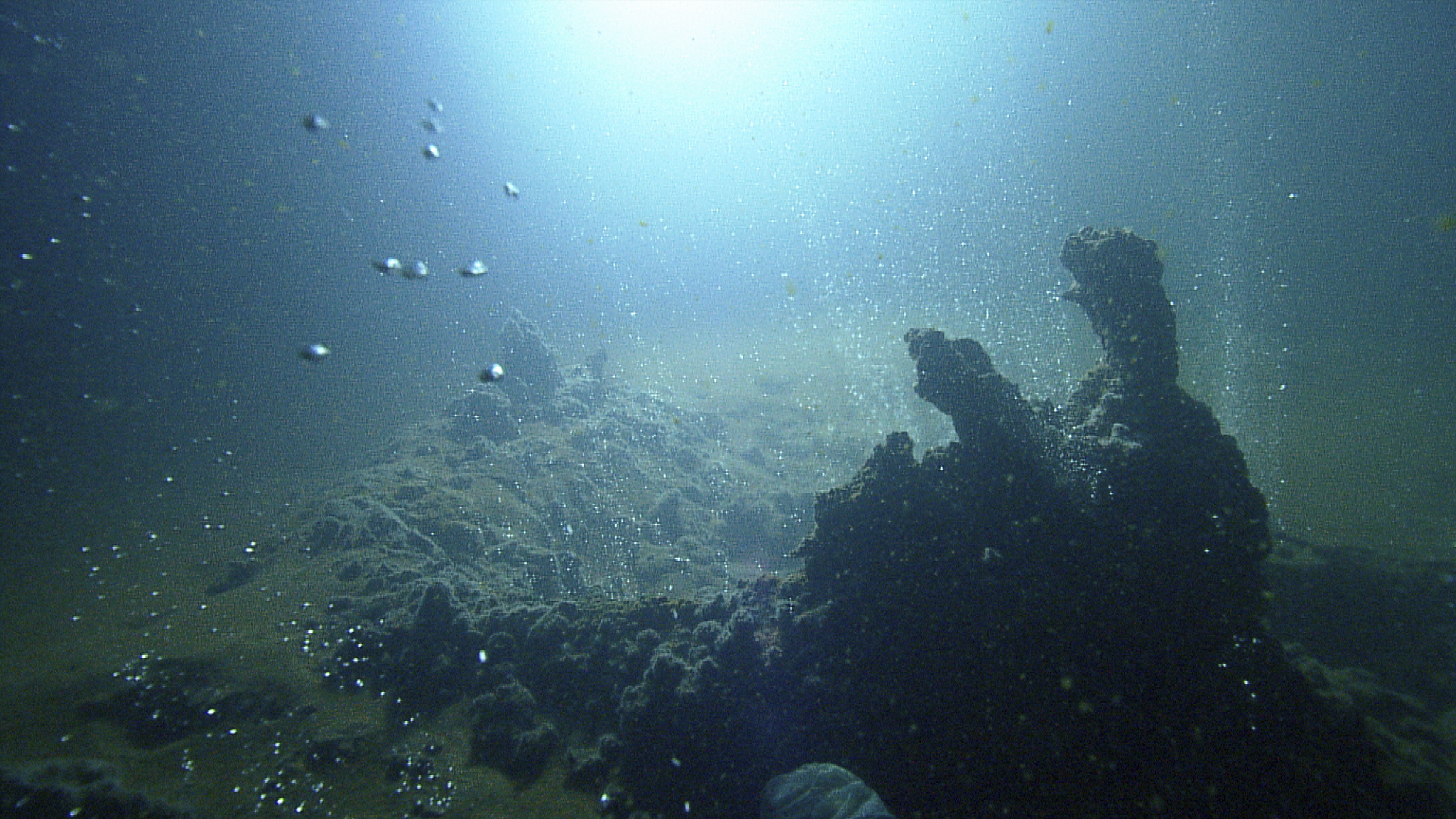

About 4 miles (7 kilometers) from Santorini, 1,640 feet (500 meters) under the ocean's surface, lies the Kolumbo volcano. Kolumbo is one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the world, and according to historical accounts, its last eruption in A.D. 1650 killed at least 70 people. A study published Oct. 22, 2022, in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems revealed that the previously undetected magma chamber growing beneath the Kolumbo volcano could lead to another eruption, thus endangering residents and tourists on Santorini.

Undersea volcanoes are monitored just like their on-land counterparts, but because undersea seismometers are challenging to install, there are fewer of them, which means scientists have less data on undersea volcanoes. In an attempt to overcome this problem, researchers decided to try a different technique to study the inner mechanics of Kolumbo.

Specifically, they used a method called full-waveform inversion, which employs artificially produced seismic waves to create a high-resolution image showing how rigid or soft the underground rock is.

"Full-waveform inversion is similar to a medical ultrasound," co-author Michele Paulatto, a volcanologist at Imperial College London, said in a statement. "It uses sound waves to construct an image of the underground structure of a volcano."

Related: Tonga eruption’s towering plume was the tallest in recorded history

Seismic waves travel at different speeds through Earth depending on the rigidity of the rock they're passing through. For example, a type of seismic wave called a P-wave travels more slowly if the rock is more like a liquid, like magma, than it does through hardened rock. By gathering data about the velocity of seismic waves traveling through the ground, researchers can get a sense of where magma is forming.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While on board a research cruise sailing near the volcano, the researchers fired an air gun, which produced seismic waves in the ground below. Those seismic waves were measured by monitors on the seafloor.

Data from the seismic recordings showed a significant decrease in velocity underneath the volcano, indicating the presence of a magma chamber, rather than just solid rock. Further calculations revealed that the magma chamber has been growing at a rate of 141 million cubic feet (4 million cubic meters) per year ever since its eruption in 1650.

The chamber now holds roughly a third of a cubic mile (1.4 cubic km) of magma, the team found.

According to study first author Kajetan Chrapkiewicz, a geophysicist at Imperial College London, the volume of magma could reach roughly half a cubic mile (2 cubic km) within the next 150 years. That was the estimated amount of magma Kolumbo ejected nearly 400 years ago.

The new study illustrates how important it is to closely monitor undersea volcanoes. Unlike earthquakes, volcanic eruptions can be predicted to some extent — but only if experts have enough data about the movement of magma beneath the volcano.

"We need better data on what's actually beneath these volcanoes," Chrapkiewicz said in the statement. "Continuous monitoring systems would allow us to have a better estimation of when an eruption might occur. With these systems, we would likely know about an eruption a few days before it happens, and people would be able to evacuate and stay safe."

For Kolumbo, an international team of scientists has been working on establishing a seafloor observatory called Santorini's Seafloor Volcanic Observatory, or SANTORY. Once the observatory is up and running, scientists and hazard experts will be better equipped to monitor for possible eruptions.

JoAnna Wendel is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon. She mainly covers Earth and planetary science but also loves the ocean, invertebrates, lichen and moss. JoAnna's work has appeared in Eos, Smithsonian Magazine, Knowable Magazine, Popular Science and more. JoAnna is also a science cartoonist and has published comics with Gizmodo, NASA, Science News for Students and more. She graduated from the University of Oregon with a degree in general sciences because she couldn't decide on her favorite area of science. In her spare time, JoAnna likes to hike, read, paint, do crossword puzzles and hang out with her cat, Pancake.