Megalodon shark mamas had human-size cannibal babies

Its young were the largest live babies in the shark family.

Megalodon was the biggest predatory shark that ever lived, and its young were also gargantuan; at birth, they were as big as the average basketball player.

How did bouncing baby megalodons fuel their impressive embryonic growth? They may have gobbled up their smaller siblings while still in the mother's womb, a survival strategy shared by some modern sharks.

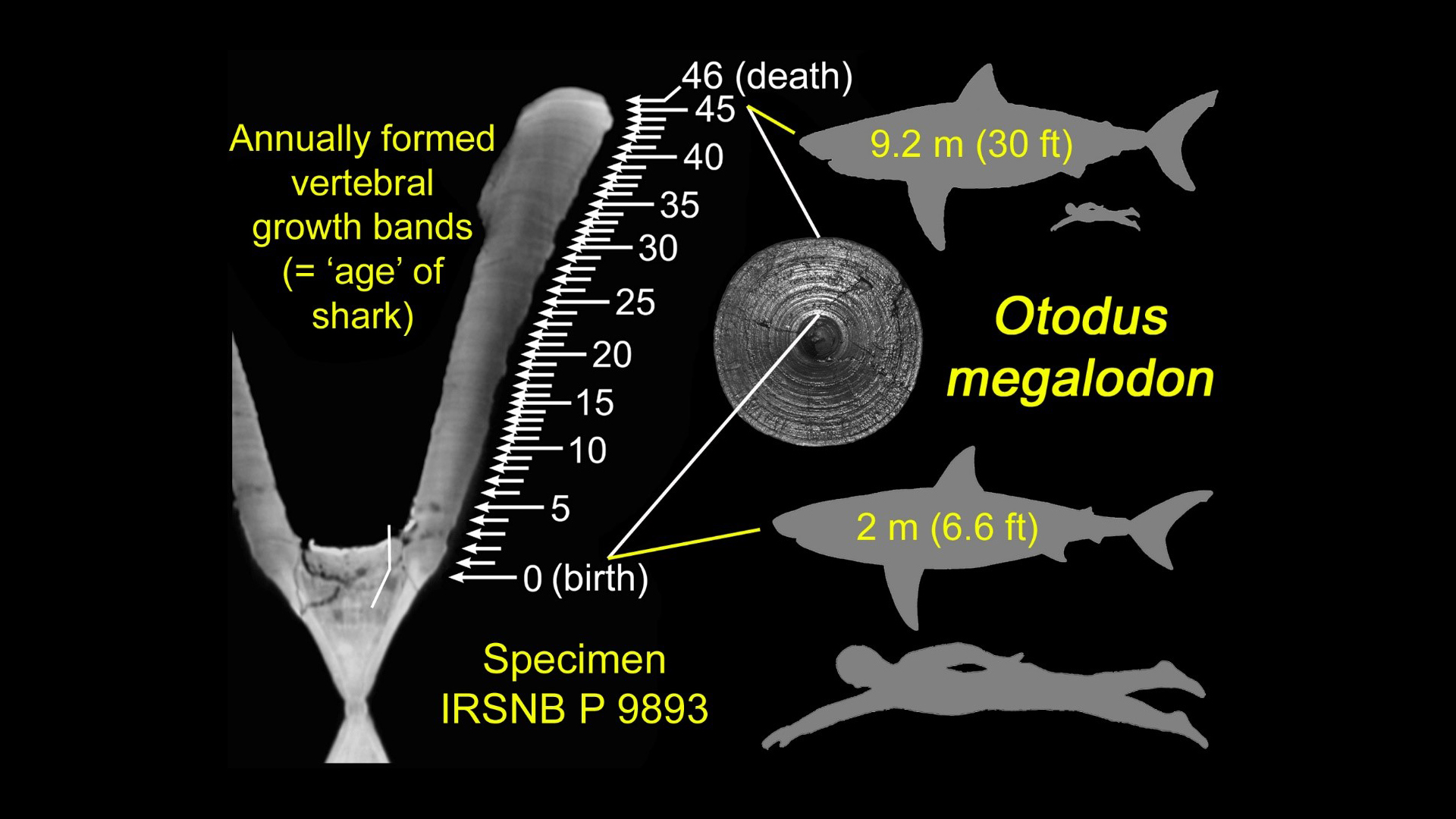

Researchers recently calculated the size of megalodon babies by analyzing skeletal fossils of an adult Otodus megalodon that measured about 30 feet (9 meters) long when it died (these monster sharks could likely reach about 66 feet, or 20 m). The scientists then looked at "growth rings" in pieces of the shark's preserved skeleton, similar to the rings in tree trunks used to determine a tree's age.

Related: 7 unanswered questions about sharks

Megalodon — and all sharks, skates and rays — belong to a class of fishes called Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons made of cartilage rather than hard bone. Extinct cartilaginous fish like megalodon and other megatooth sharks are therefore known mostly from their teeth, which were made of calcium and therefore survive in the fossil record longer than these fishes' delicate cartilaginous skeletons.

But for the new study, published online Jan. 11 in the journal Historical Biology, the authors examined a rare collection of 150 megalodon vertebrae whose cartilage had mineralized, "the only reasonably preserved vertebral column of the species in the entire world," they wrote.

Using computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans, the scientists counted 46 regularly-spaced growth rings in three of the megalodon's vertebrae. They then applied a mathematical growth curve equation that's commonly used to calculate growth patterns in modern sharks, based on growth bands in their spinal cartilage, said lead author Kenshu Shimada, a professor of paleobiology at DePaul University in Chicago and research associate at the Sternberg Museum in Kansas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each ring represented a year of growth, so the shark would have been about 46 years old when it died. By working backwards to the earliest growth ring — the "band at birth" — the scientists calculated the shark's length as a newborn, estimating it to be around 6.6 feet (2 meters) long — bigger than any known newborn sharks. While prior studies had noted the presence of these rings in megalodon fossils, "no detailed analyses had been conducted prior to this new study," Shimada told Live Science in an email.

Such large babies would likely have been born live, the study authors reported. Nourishing such enormous young would have carried high energy costs for the mother, suggesting that her babies supplemented in-utero nutrients with a side helping of unborn sibling cannibalism, Shimada said.

"Oophagy — egg-eating — is a way for a mother to nourish its embryos for an extended period of time," he explained. "The consequence is that, while only a few embryos per mother will survive and develop, each embryo can become quite large at its birth."

Examination of the vertebrae's rings also revealed the shark probably grew slowly, with a slightly higher growth rate during its first seven years of life. Based on the space between rings, the megalodon didn't experience a rapid growth spurt in its youth as some animals do. Perhaps that's because it was already big enough at birth to compete for food and discourage predator attacks, the study authors reported.

By combining the growth trajectory findings with data about body size in the largest known individuals, the researchers estimated that megalodon sharks may have lived to be at least 88 to 100 years old. However, this inferred life expectancy "remains rather theoretical and needs further investigation," Shimada said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.