Megalodon's mortal attack on sperm whale revealed in ancient tooth

The megatoothed shark's serrated teeth left gouge marks.

Millions of years ago, an ancient sperm whale had a very, very bad day when a megatoothed shark — possibly the fearsome Otodus megalodon or its ancestor Otodus chubutensis, the largest predatory sharks that ever lived — viciously attacked it in what is now North Carolina, a new study suggests.

Marks from the attack, preserved as gouges out of the sperm whale's tooth, are the first evidence in the fossil record that megatoothed sharks tussled with sperm whales, the researchers said.

"It would seem that these giant sharks were preying on whatever they wanted to, and no marine animal was safe from attacks from these giant sharks," study lead researcher Stephen Godfrey, curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, Maryland, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: These animals used to be giants

The single tooth is all that's left of the ancient sperm whale. Study co-researcher Norman Riker, an amateur fossil collector from Dowell, Maryland, found the tooth in what is now called the Nutrien Aurora Phosphate mine, a large phosphate mine in Aurora, North Carolina, in the 1970s or 1980s, when the mine was open to fossil collectors. (Riker, who donated the tooth to the Calvert Marine Museum, died at age 80 in January 2021, the museum newsletter reported.)

The researchers aren't sure when this shark-whale brawl occurred. To reach the older phosphate-rich beds, mine workers removed bucketloads of overlying sedimentary rock and dumped them nearby, where fossil collectors could scour them, Godfrey said. The different rock layers — which get laid down over time and so are used to date objects in the layers — got mixed up; because of the mixing, the scientists don't know if the tooth comes from the older sedimentary beds, which would date it to the Miocene epoch, 14 million years ago, or the younger fossils beds, which would date it to the Pliocene epoch, about 5 million years ago.

Either way, the tooth falls into the Neogene period (23 million to 2.5 million years ago), he noted. During the Neogene, the Earth's climate was warmer than it is today and, as a result, the North and South Poles had less ice, so sea levels were higher. That's why "coastal North Carolina was covered by a vast shallow arm of the Atlantic Ocean," Godfrey said. "These marine waters teemed with abundant sea life."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shark versus whale

The size and shape of the curved 4.5-inch-long (11.6 centimeters) tooth clearly indicates that it belongs to an extinct sperm whale species, Godfrey said. By using an equation that compares extinct sperm whale tooth size with body size, the researchers estimate this particular whale was small, only about 13 feet (4 meters) long. Today's sperm whales can reach lengths of over 50 feet (15 m), Godfrey noted.

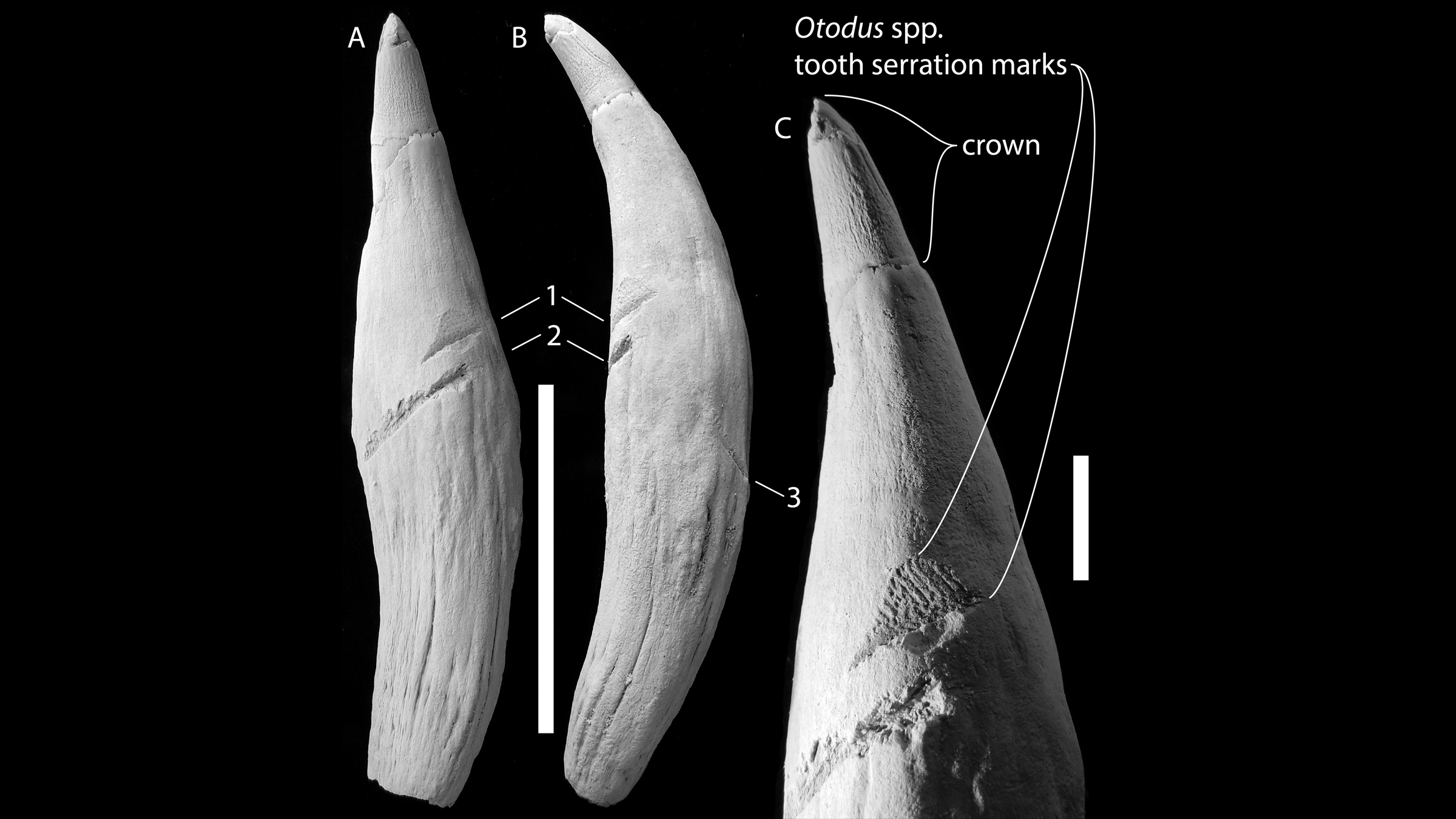

Three gouge marks on the tooth show that whatever took a bite out of it had evenly spaced, serrated teeth. Based on the size and spacing of the bite marks and serrations, the only possible culprits are the megatoothed shark O. chubutensis (which lived 28 million to 13 million years ago) and its descendant O. megalodon (which existed 20 million to 3.5 million years ago), the researchers found.

"None of the other fossil sharks known from the phosphate mine have teeth large enough and serrations even enough to have left these bite traces on the sperm whale tooth," Godfrey wrote in the email. "Up until now, bite traces by these giant sharks (with a body length of megalodon over 60 feet [18 m] long) have been found on other bones of extinct whales and dolphins, but never on the head or other bones of a sperm whale."

Related: Image gallery: Russia's beautiful killer whales

The team added that while it's possible the megatoothed shark was scavenging an already-dead sperm whale, it's more likely that that gouge marks were made during a predatory attack. That's because the cut marks were made on the root of the tooth, or the part that was embedded in the whale's jaw. "So before the megatoothed shark tooth could cut into the sperm whale tooth, it first had to cut through the jaw bone of the sperm whale holding the tooth," Godfrey said.

"It would seem unlikely that a large shark would target the jaws of a floating or seafloor carcass of a sperm whale. There would be little flesh in return for the effort," he continued. Instead the bite marks "hint at an attack to the head with the goal of inflicting a mortal wound. In other words, if a giant shark is biting your head, it's trying to kill you."

The findings shed light on the ancient ecology of North Carolina, said paleontologist Alberto Collareta, of the University of Pisa in Italy who was not involved in the study. Moreover, it's not too surprising that the megatoothed shark bit the sperm whale's tooth, he said. Killer whales, apex predators in today's oceans, are known to eat the meaty tongues and blubbery throats of other whales. "Maybe the sperm whales had some reserve of fat or there was the tongue," that attracted the megatoothed shark, Collareta told Live Science.

The study was published online Aug. 9 in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.