There's trouble brewing at the edge of the Milky Way: New measurements suggest that a peculiar distortion of the galactic disk is hardly moving, contradicting earlier reports.

As yet, nobody knows which finding will end up being correct. At stake are some key details in the structure and formation of spiral galaxies throughout the universe.

Astronomers describe the Milky Way as a flat disk-shaped, double-armed spiral galaxy twirling and twinkling with stars. Yet since the mid-20th century, astronomers have known that this picture is partially wrong.

Related: 11 fascinating facts about our Milky Way galaxy

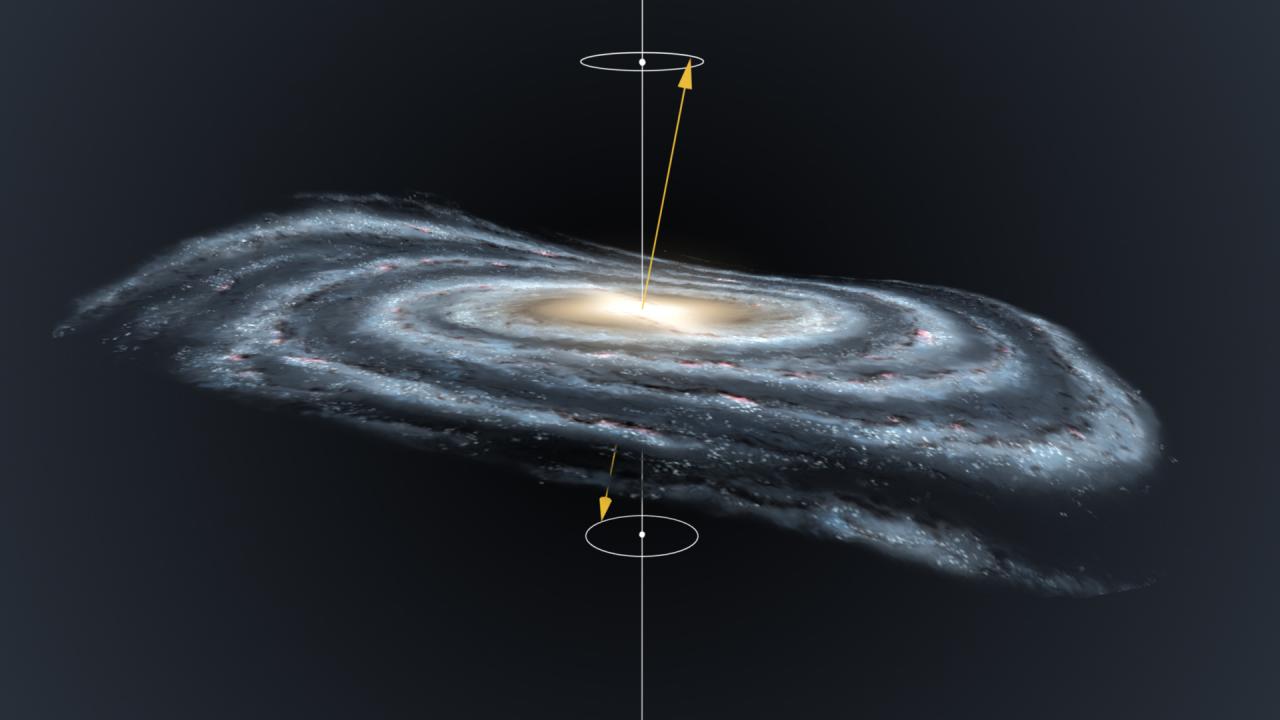

Observations in the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum first revealed that our galaxy's farthest borders are warped, with some parts drooping down and other parts bending upward, like a vinyl record left on a hot plate.

Subsequent data have shown that this feature, known as a galactic warp, is common for spiral galaxies, Žofia Chrobáková, an astrophysics doctoral candidate at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC) in Spain, told Live Science.

Different explanations have been offered for the warp's formation, such as the possibility that it arises from surrounding material falling onto the galactic disk, Chrobáková said. In that case, the distortion would likely be static or moving extremely slowly.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But other theories have posited that warps are fashioned through more dynamic mechanisms, such as interactions with dark matter at the edge of a galaxy, or smaller galaxies orbiting their larger brethren, tugging on them gravitationally and generating ripples. These ideas would lead to an active warp that might be spinning around like a top, a movement known as precession.

"If we know how fast or if the warp rotates, it could be like a piece of a puzzle," Chrobáková said. "It tells us a lot of information about how the warp was created."

Last year, a team writing in the journal Nature Astronomy used information from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite — which provides ultraprecise measurements of the location of the Milky Way's stars — to deduce that our galaxy's warp was spinning. A second paper, published in December in The Astrophysical Journal, corroborated these results, suggesting that the warp was zipping along rather quickly, orbiting with a period of around 600 million to 700 million years.

If that were the case, the procession would be nearly 10 times faster than previous models had predicted, Chrobáková said.

But in a new study, she and her co-author Martín López-Corredoira, also of IAC, put the brakes on the prior measurements. By looking at the same Gaia data but modeling the details differently, Chrobáková and López-Corredoira found that the warp is moving about 3.4 times more slowly than the results announced last year suggested. Their findings appeared May 13 in the The Astrophysical Journal.

"My research puts down this new breakthrough and says we are back to where we started," Chrobáková said. "We call it an anti-discovery."

Yet the error bars on Chrobáková's measurements are large enough to leave the matter unsettled, said Ronald Drimmel, an astronomer at the University of Turin in Italy who was part of the team that first measured a precessing warp.

"It might be indicating that there's no motion, or that it has a large motion," he told Live Science. "There's quite a bit of uncertainty."

Much of the disagreement comes down to the precise shape of the warp itself, which neither team has a perfect handle on, Drimmel said. "Making such measurements is hard. We're right in the disk of the galaxy, and dust clouds limit how far we can see."

Chrobáková agreed that additional data will be necessary to solve this conundrum. Next year, Gaia is expected to release a new catalog that could provide additional information for this dust-up.

That's good, because other galaxies are likely too far away to be able to settle the debate. "The Milky Way is the galaxy we have the best chance of exploring in such detail," Chrobáková said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.