Medium-size dinos are missing from the fossil record. Here's why.

It's hard to compete against teenage tyrannosaurs.

Medium-size meat-eating dinosaurs are missing from the fossil record, and paleontologists think they've figured out why.

Paleontologists have discovered gargantuan dinosaurs and wee dinosaurs, but a new study finds that there's a conspicuous lack of medium-size carnivorous dinosaur species, especially from the Cretacous period (145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago).

Donning their detective hats, the researchers soon found a suspect; megatheropods — the largest of the meat-eating dinosaurs, like Tyrannosaurus rex and Gorgosaurus, which weighed over 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms) as adults. It's possible that juvenile megatheropods edged out the middlings, the researchers said.

"Juvenile megatheropods may have outcompeted other medium-sized dinosaurs, resulting in deflated global dinosaur diversity," study lead researcher Katlin Schroeder, a doctoral student in the Department of Biology at the University of New Mexico, told Live Science in an email.

However, not everyone is convinced that there is a case of missing medium-size dinosaurs; it's possible, for instance, that there are fossils of medium-size beasts that have yet to be found, said Michael D'Emic, an associate professor in the Department of Biology at Adelphi University in New York, who wasn't involved in the study.

Related: Gory guts: Photos of a T. rex autopsy

Small, medium, large

As egg-laying animals, all dinosaurs started out small, weighing no more than 33 pounds (15 kg) as hatchlings. As dinosaurs grew, some likely occupied different niches and ate different foods than adults of the same species did — for instance, a young T. rex likely couldn't take on a Triceratops, and probably went after smaller prey.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

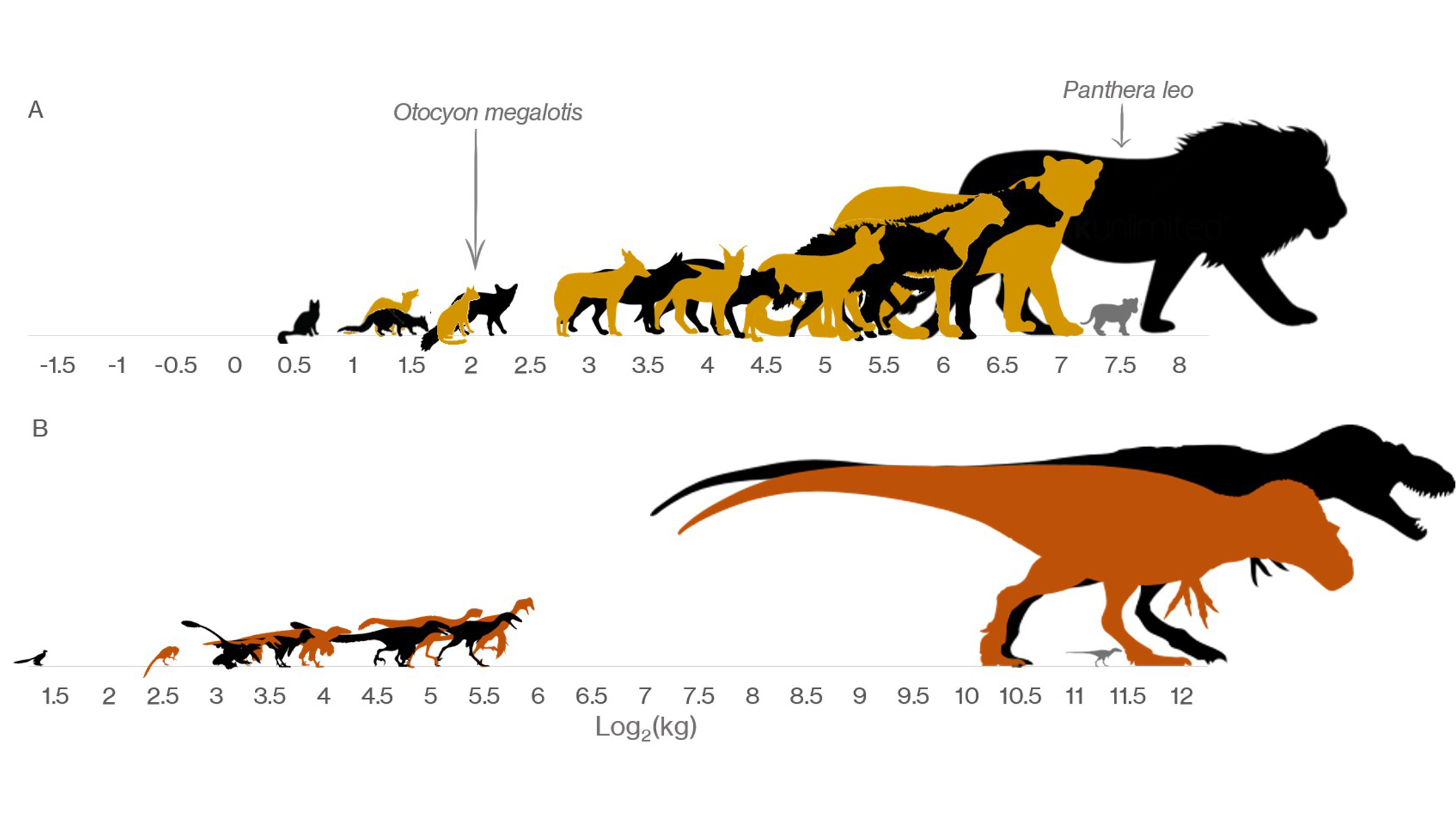

To investigate the medium-size mystery, Schroeder and her colleagues logged onto the Paleobiology Database, a nonprofit resource for paleontological data, and they categorized more than 550 dinosaur species as small (22 to 220 pounds, or 10 to 100 kg), medium (220 to 2,200 pounds, or 100 to 1,000 kg) or large (over 2,200 pounds, or 1,000 kg). These dinosaurs lived within 43 communities (groups that lived in the same time and place) across seven continents during the Jurassic period (201 million to 145.5 million years ago) and the Cretaceous period.

The researchers found that while communities often had herbivorous dinosaurs in each size category, it was rare to spot a medium-size carnivorous dinosaur in communities with megatheropods.

"It's possible that the 'gap' was being caused by juveniles of those large megatheropods, which may have been eating different things than their parents, and therefore competing with medium-sized carnivores," Schroeder said.

The team found the medium-size dinosaur gap was more pronounced in the Cretaceous than in the Jurassic period. During the Cretaceous period, the tyrannosaurs and the abelisaurs were king, and they also looked "very different as juveniles than they do as adults," unlike the megatheropods of the Jurassic, she said.

In other words, during the Jurassic period, the megatheropods, such as Allosaurus, didn't change much as they grew, "and may have actually been sharing food resources, such as giant sauropods [long-neck herbivorous dinosaurs] with their parents," Schroeder said. "This may have allowed more carnivores to coexist in the same communities, resulting in a smaller [medium-size] gap in carnivores."

But at the end of the Jurassic, a lot of the sauropods went extinct, and so did dinosaurs like Allosaurus. "They may have been replaced by dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus that used a wider variety of different resources as they grew," Schroeder said.

Next, Schroeder's team wondered whether the juvenile megatheropods had a bigger effect on the composition of their communities than the adults did. To find out, the researchers calculated how many juveniles and adults each species had in a community. Then, the team figured out the biomass — the number of individuals in a species multiplied by their mass at a certain age.

Related: In Photos: Bizarre 'bat dinosaur' discovered in China

The researchers found that in some megatheropod species, such as Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, the juveniles represented a larger portion of mass than the adults, likely because it was a dinosaur-eat-dinosaur world back then, and megatheropods didn't always make it to adulthood. This indicates "that the juveniles had just as much (if not more) effect on their community than the adults did," Schroeder said in the email. In fact, there were so many medium-size megatheropod juveniles, they could even be viewed as their own species, in a manner of speaking.

"When we added the juveniles to the communities as their own [species], the gap largely disappeared," Schroeder said.

However, it's possible that something else could explain this medium-size mystery, D'Emic said. Twelve out of 43 of the paleo-communities examined in the study don't seem to follow the pattern inferred in the study — that medium-size carnivorous dinosaurs were rare in communities with megatheropods. In these 12 communities, "they have both large and medium-sized theropods," D'Emic said. The study explains these exceptions in various ways, but maybe medium-size carnivorous dinosaurs were out there, it's just that paleontologists haven't found their fossils in every community yet, D'Emic said. "Even in relatively well-explored places around the globe, new dinosaur species are discovered each year, so this is not implausible," D'Emic told Live Science in an email.

I's also possible that some dinosaur species in the study were misidentified. Only recently have paleontologists begun to assess bone microstructure, which can reveal a dinosaur's age at death. "This can show that some small dinosaur individuals belonging to one species were simply juveniles of other species, or conversely, that some small dinosaur individuals thought to be juveniles of one species are instead adults of new dwarf species," D'Emic said.

The study was published online Feb. 25 in the journal Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.