Should everyone get a monkeypox vaccine?

The supply of vaccines is already limited.

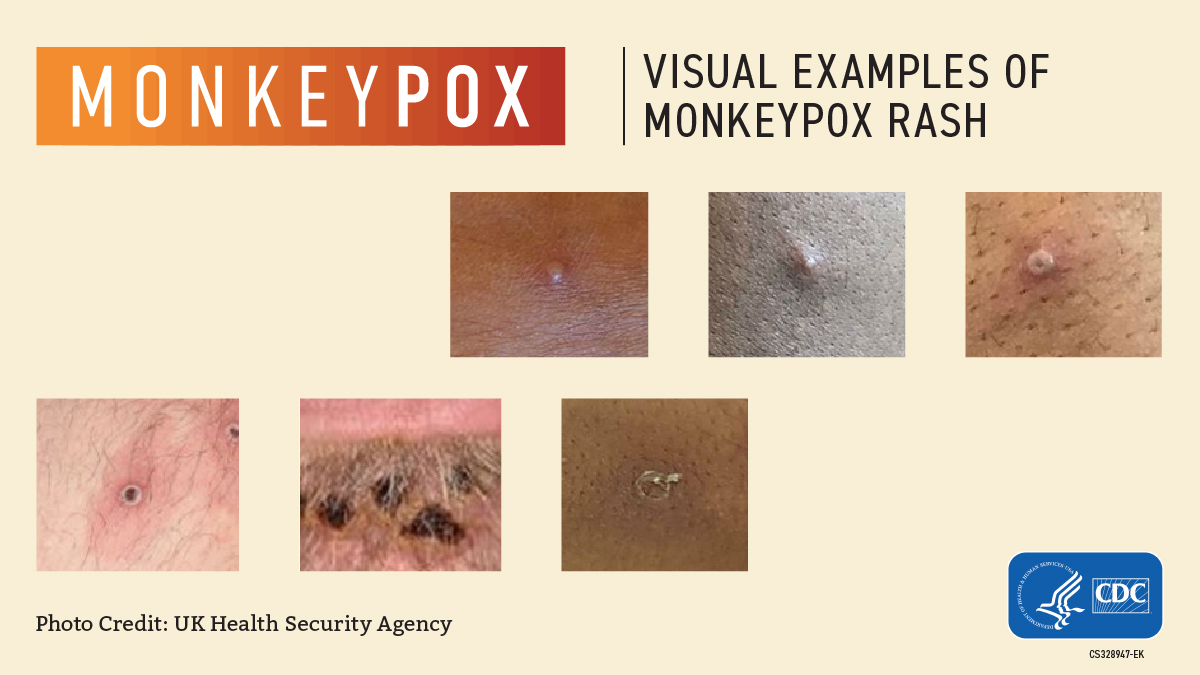

Since May, about 54,400 cases of monkeypox have been reported in 93 countries where the virus does not typically spread. In the U.S. alone, more than 20,700 cases have been identified so far. Many of these cases have turned up in men who have sex with men, but anyone, regardless of their sexual orientiation or behavior, can catch and spread monkeypox, which is transmitted mostly through close physical contact, including both sexual and nonsexual contact.

In recent weeks, there have been hints that the rate of transmission within households and via other nonsexual routes of spread — for instance, in the workplace — may be increasing, according to a Sept. 1 technical report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Officials remain concerned that the virus may start to spread widely in additional social networks, beyond men who have sex with men, and in congregate settings, such as daycares, schools, colleges and prisons.

So, given that there's some chance of monkeypox spreading more widely in other settings, will everyone eventually be advised to get a monkeypox vaccine? And if officials do expand the vaccine eligibility criteria, would there even be enough vaccines to go around?

Experts told Live Science that it's unlikely everyone will be asked to get a monkeypox vaccine anytime soon, especially considering the short vaccine supply. That won't change unless the virus starts spreading widely in places such as daycares, schools or college campuses.

Related: 1st suspected case of human-to-dog monkeypox transmission reported in France

"It's definitely 'wait and see' at this point," Rachel Roper, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, told Live Science. Depending on how the virus spreads in the coming weeks, Roper said that officials may attempt to stretch the vaccine supply to additional populations, but it's unclear what level of spread would prompt such a move.

"If we get a number of outbreaks in daycare centers, that might begin to tip it," she suggested.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For now, the CDC recommends monkeypox vaccinations for close contacts and recent sexual partners of people with confirmed monkeypox infections. That's because, if someone's been exposed to the virus and receives a vaccine within the next few days, the shot can reduce the severity of their symptoms or to prevent the illness altogether. It's thought that this can also reduce their chances of spreading the virus further, although this idea is mostly based on studies of smallpox, a related poxvirus, STAT reported.

The CDC also recommends that men, transgender people and gender-diverse people who have sex with men consider a vaccine, especially if they've recently had group sex or sex with multiple partners, or had sex at an event or venue, or in an area where monkeypox transmission is occurring.

Based on the currently available data — although that data is likely incomplete — these populations still seem to be at highest risk of infection, Dr. Ellen Carlin, an assistant research professor at Georgetown University's Center for Global Health Science and Security, told Live Science.

So for now, the focus should be on getting these groups fully vaccinated against monkeypox, while also collecting data to see whether booster doses might be necessary, said Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist and the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota. "That will have a tremendous impact on how much spillover occurs," he told Live Science.

That said, at the moment, "there's not even enough vaccine to go around for that population," Carlin said.

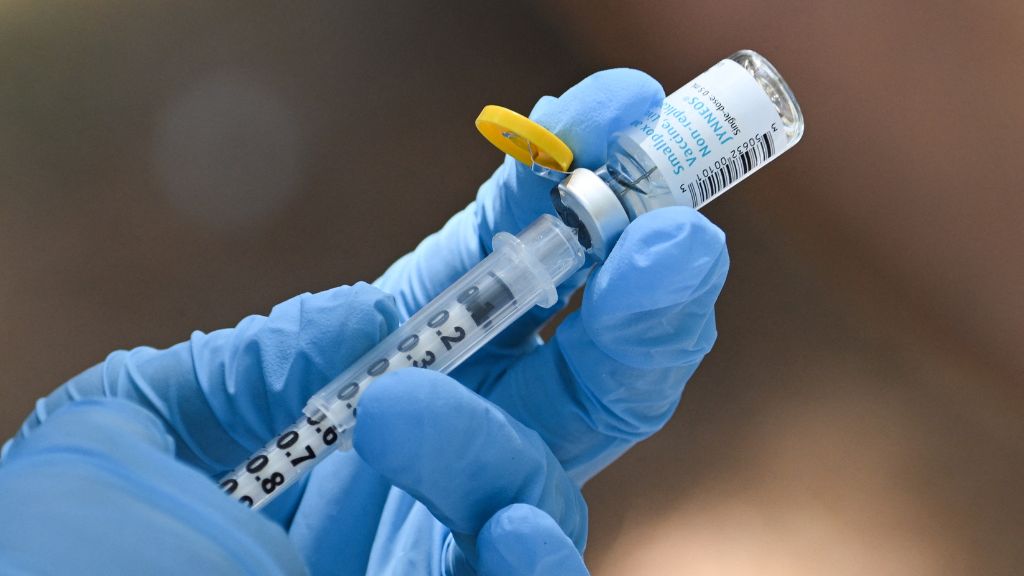

Within the U.S., two vaccines, called JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, are used to prevent monkeypox, but ACAM2000 is not recommended for widespread use. That's because the single-dose vaccine, originally developed to prevent smallpox, carries a risk of serious side effects for certain groups, including pregnant people and those with weakened immune systems, heart disease or skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis or dermatitis, among others, according to the CDC. These side effects include inflammation and swelling of the heart (myocarditis) and surrounding tissues (pericarditis), and the risk is high enough that the CDC states that ACAM2000 should not be given to the aforementioned groups.

ACAM2000 can also pose risks to close contacts of a vaccinated person if those contacts fall into one of the high-risk groups listed above. The vaccine contains live vaccinia virus — a relative of the viruses that cause smallpox and monkeypox — and is given via skin pricks in the upper arm, which creates an open sore, or "take," at the vaccination site.

"The problem is live virus can actually transmit from that wound to other people," Carlin said, so vaccinated people must isolate themselves from vulnerable individuals as they heal. This is not a concern with the JYNNEOS vaccine, the primary vaccine being used in the current outbreak.

One problem with JYNNEOS, however, is that there's not a lot to go around.

The U.S. held a small number of JYNNEOS doses in its Strategic National Stockpile at the start of the outbreak, but officials soon had to order more, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). And until recently, the vaccine could be produced and packaged only by the Denmark-based company Bavarian Nordic, which can reportedly produce 30 million to 40 million doses a year, a spokesperson told NPR. Using the standard two-dose regimen, administered 28 days apart, this supply could cover about 15 to 20 million people. But it takes time to make and deliver all those doses, and it's uncertain if the outbreak will spill to additional social networks in the lag time.

Related: Monkeypox may present with unusual symptoms, CDC warns

On that front, "I think it's still possible to contain it — that's my guess," Roper told Live Science. However, "I'm concerned there might be a lot more cases that we might not know about," she noted.

Carlin agreed that the true number of monkeypox cases in the U.S. is likely higher than reported, but she's less confident that the outbreak can be stopped before it reaches additional social networks. "I'm not optimistic that we can snuff it out," she said. "I'd be glad to be proven wrong."

In an attempt to stop the spread, the HHS recently struck a deal to bottle and package JYNNEOS in the U.S. — a move that could help boost the nation's vaccine supply more quickly. In addition, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently expanded its guidance on how the vaccine can be administered in order to cover more people with the available supply. Normally, a full dose of the vaccine would be injected into the layer of fat under the skin (subcutaneously). Now, with the right needles and training, health care providers can instead inject the vaccine into the outer layers of the skin (intradermally) and at one-fifth the standard dose.

In the U.S., most vaccines are injected into the muscle (intramuscularly), while only a few are recommended as subcutaneous injections, according to the CDC. Globally, only the rabies vaccine and Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine for tuberculosis, which is not widely in the U.S., are regularly given intradermally, according to the World Health Organization. But scientists have run promising trials with additional vaccines, including those against influenza and hepatitis B, that suggest these shots could also be given intradermally. The appeal of intradermal delivery is that the skin is rich in immune cells that are "really effective" at responding to vaccines, so this route of vaccination can often elicit strong immune responses at lower doses than subcutaneous shots, Carlin said.

A small 2015 study published in the journal Vaccine hinted that this also may be the case for JYNNEOS, but there's still uncertainty as to whether the adjusted dosing strategy will pan out in the current outbreak, STAT reported.

Should the need arise, Carlin said she wonders if federal health officials would clear ACAM2000 for widespread use, despite the potential health risks. According to the HHS, there were more than 100 million ACAM2000 doses in the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile as of July 1. (Although smallpox has been eradicated, the nation has maintained a supply of the vaccine in case the virus was ever used as a bioterrorist weapon.)

While many groups are advised against taking the vaccine, others would be just fine, Carlin said. But even so, she said remains "skeptical" about rolling out the vaccine in the current outbreak.

"I would urge not doing that," Osterholm said of using ACAM2000 widely. When the shot was used to prevent smallpox, the potential risks of the disease outweighed the risks of receiving ACAM2000, but this isn't necessarily the case for monkeypox, which is typically a mild illness, he said.

It's key to note that, while JYNNEOS is approved for use in adults ages 18 and older, the vaccine can be offered to children through a special expanded use protocol, according to the CDC. The vaccine was given to a few children, including infants, during a previous outbreak in the U.K., and it's been given to some children in the U.S. during the current outbreak "without any adverse events to date." ACAM2000 can also be used in children as young as 1 year old under a similar expanded use protocol.

Children younger than 8 face a greater risk of developing severe monkeypox infections than the general public, so it would be particularly concerning if the virus began spreading in this age group, Roper said. For now, though, the data don't suggest that's happening, and "right now, I just don't think that we have enough signals from the data to justify a particular expansion" of the vaccine eligibility criteria, Carlin said.

As Roper surmised, we'll just have to wait and see what happens.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Sept. 12 to clarify that most vaccines given in the U.S. are injected intramuscularly. The story was first published on Sept. 8.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents