Monster bird fossils unearthed in Antarctica

The birds' wingspans were as wide as a U-Haul truck is long.

Not long after the dinosaurs went extinct, a new breed of giants rose: Monster birds with wingspans that stretched up to 21 feet (6.4 meters) long, about the length of a U-Haul truck.

These enormous birds darkened the skies above Antarctica as early as 50 million years ago, a new examination of fossils from the continent finds. The new research reveals that very large species of these birds, called pelagornithids, arose less than 15 million years after an asteroid wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs.

The new study was published Oct. 27 in the journal Scientific Reports. It focused on a bone from a bird's foot, collected on Seymour Island near the Antarctic Peninsula in the 1980s. In 2015, Peter Kloess, a University of California, Berkeley, paleontology graduate student found the bone in the collections of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. As he looked over the notes accompanying the bone, he realized that the bones were from older rock than had originally been recognized. Instead of being 40 million years old, as it said on the label, the bone was 50 million years old, and far larger than other pelagornithid bones found of that age.

Related: 25 amazing ancient beasts

"I love going to collections and just finding treasures there," Kloess said in a statement. "Somebody has called me a museum rat, and I take that as a badge of honor. I love scurrying around, finding things that people overlook."

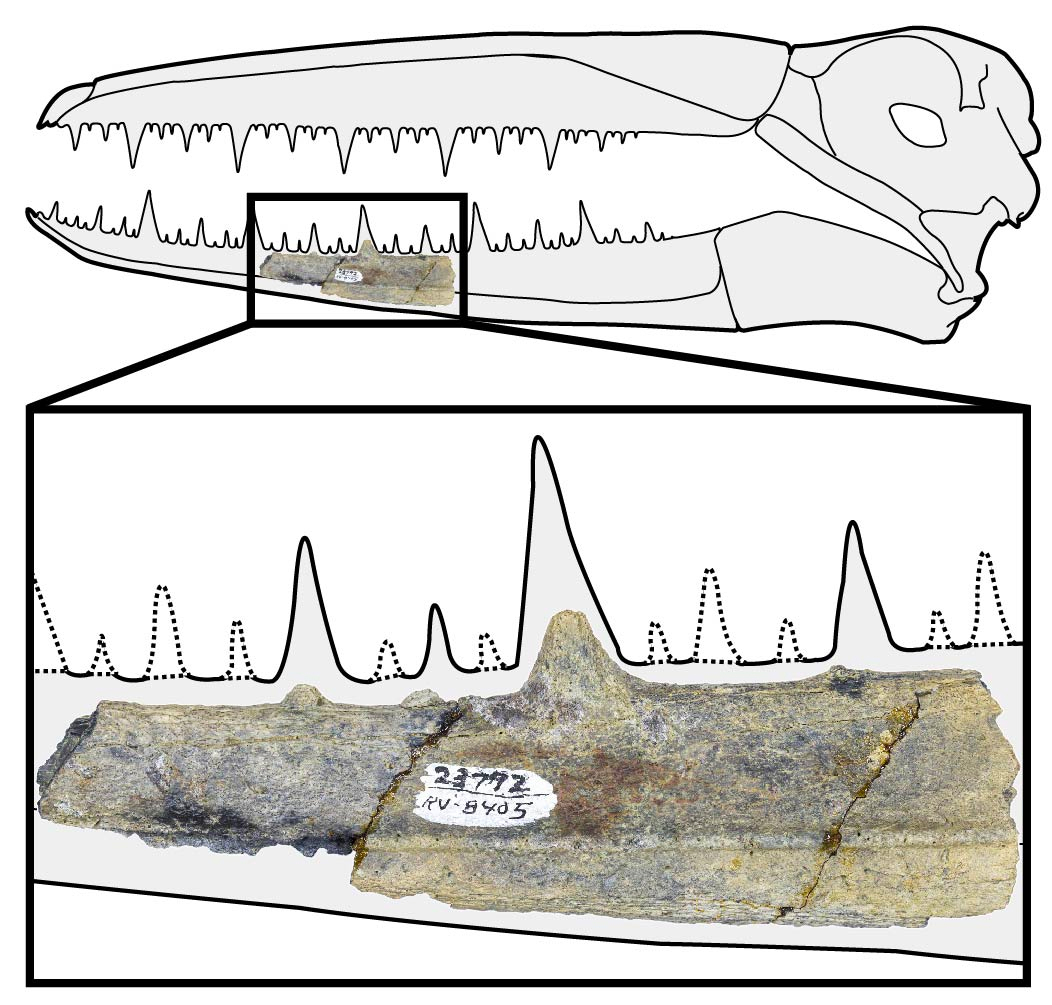

The bone was overlooked no longer. Kloess and his colleagues discovered another pelagornithid bone from the same island and era — a partial lower jaw. Analyzing them both, the researchers concluded that the bird's skull would have been 2 feet (60 centimeters) long. The animal would have been among the biggest, if not the biggest, pelagornithid ever found.

Pelagornithids were known to be a very old group of birds. The oldest fossil from these birds dates back 62 million years. However, that fossil was from a species much smaller than the one discovered by Kloess and colleagues.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newly discovered birds were more similar to the modern-day albatrosses, with huge wingspans that would have allowed them to soar for days or even weeks at a time over the open ocean. Modern-day albatross, however, top out with wingspans of 11.5 feet (3.5 m). The 50-million-year-old pelagornithid would have had a wingspan nearly double that.

The beaks of these ancient sky monsters also had bony projections covered in keratin. These toothlike structures, about 1 inch (3 cm) tall, would have helped the birds hang on to fish and squid scooped from the seas.

Fifty million years ago, Antarctica was warmer than it is today. It was a haven for birds, including early penguins, as well as now-extinct mammals, such as the hoofed sparnotheriodontids, according to a 2014 study in the journal Paleontology. Large pelagornithids likely dominated the skies.

"[T]hese bony-toothed birds would have been formidable predators that evolved to be at the top of their ecosystem," study co-author Thomas Stidman of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in the statement.

Pelagornithids likely boasted the largest wingspan of any bird, followed by a group of scavenging birds called teratorns, which evolved 40 million years later. (Some pterosaurs had them both beat: Questzalcoatlus northropi, for example, could extend its giant wings up to 43 feet, or 13 m.) The last pelagornithids went extinct 2.5 million years ago.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.