Here are the most promising coronavirus vaccine candidates out there

Editor's Note: This story was updated on Nov. 25.

Using materials from weakened cold viruses to snippets of genetic code, scientists around the world are creating dozens of unique vaccine candidates to fight the novel coronavirus — and they're doing it at unprecedented speeds.

It's not known exactly when the virus hopped from animals to humans and when it started spreading across borders. But in less than a year since the World Health Organization (WHO) first alerted the world to a mysterious cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China, researchers across the globe have already developed more than 200 different candidate vaccines to fight the coronavirus.

Most are in preclinical stages, meaning they are still being tested on animals or in the lab, but 48 of them are being tested on humans. A handful of those 48 have reached late-stage clinical trials and three have already revealed promising results in late-stage trials and have applied for emergency use among high-risk populations. The first doses of a COVID-19 vaccine could be given to people in the U.S. starting in December.

Related: Coronavirus live updates

Clinical trials are broken up into three to four stages, with earlier stages (phase 1/phase 2) examining the safety, dosage, and possible side effects and efficacy (how well it works at fighting the pathogen) of the candidate vaccine in a small group of people, according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The key to getting a candidate vaccine approved, however, is showing promising results in the more advanced phase 3 trial. In phase 3 trials, researchers test the efficacy of the vaccine, while also monitoring for adverse reactions in thousands of volunteers.

Here are the most promising of those candidates:

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

University of Oxford/AstraZeneca

The vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, popularly known as the Oxford vaccine, was developed by researchers at the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca. The vaccine candidate is 70% effective in preventing COVID-19 and can be 90% effective when given in the right dose, the University of Oxford announced on Nov. 23. The vaccine is given in two doses, 28 days apart and is still being tested in phase 3 clinical trials across the globe, including in the U.S., U.K. and Brazil. The first analysis from these late-stage trials was based on 131 participants who developed COVID-19 after receiving either the vaccine or the placebo. In those who received two full doses, the vaccine was around 62% effective in preventing COVID-19, but in those who first received a half dose and then a full dose (this dosing wasn't deliberate, but the result of dosing mistake in early trials), the vaccine was 90% effective, Live Science reported. However, the data is not yet released or peer-reviewed and so it's not clear how many people received the placebo and how many received the vaccine.No serious safety concerns were found, and none of the participants who developed an infection after receiving the vaccine were hospitalized or had serious disease, according to the statement. The trials were paused twice before (this is common in clinical trials) after two different participants developed neurological symptoms, but they were resumed again when investigators didn't find a link between the vaccine and the symptoms, according to Vox. Another participant in the trial, a 28-year-old doctor in Brazil, died from COVID-19 complications, but the University of Oxford didn't cite any safety concerns nor was the trial stopped, so it's likely he was given a placebo and not the vaccine itself, according to the BBC.

The vaccine is made from a weakened version of a common cold virus, called an adenovirus, that infects chimpanzees. Researchers genetically altered the virus so that it couldn't replicate in humans and added genes to code for the so-called spike proteins that the coronavirus uses to infect human cells. In theory, the vaccine will teach the body to recognize these spikes, so that when a person is exposed, the immune system can destroy it, according to a previous Live Science report.

Researchers previously tested this vaccine in rhesus macaque monkeys and found that it did not prevent the monkeys from becoming infected when deliberately exposed to the coronavirus, but did prevent them from developing pneumonia, suggesting that it was partially protective, according to a study published May 13 to the preprint database BioRxiv.

In April, researchers began testing the vaccine on people and published early results from their phase 1 and still-ongoing phase 2 trials on July 20 in the journal The Lancet. The vaccine didn't cause any serious adverse effects in participants but did prompt some mild side effects, such as muscle ache and chills. The vaccine spurred the immune system to produce SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cells — a group of white blood cells important in the fight against pathogens — and neutralizing antibodies, or molecules that can latch onto the virus and block it from infecting cells, according to the report.

The Oxford vaccine showed similar immune responses in those over the age of 56 and those between the ages of 18 and 55, and it was "better tolerated" in older adults than younger adults, according to phase 2 results published on Nov. 18 in the journal The Lancet. This analysis was based on 560 participants, 240 of them 70 years of age and older.

The team at Oxford has also expressed interest in conducting challenge studies on humans, meaning they would deliberately infect low-risk volunteers with the virus, either alongside phase 3 trials or after they are complete, according to The Guardian.

Sinovac Biotech

A Chinese company, Sinovac Biotech, developed and is testing a candidate vaccine called CoronaVac, which is made up of an inactivated version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Inactivated vaccines use killed versions of a pathogen (as opposed to weakened viruses, which are called live vaccines), according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Inactivated viruses such as the flu vaccine or the hepatitis A vaccine, are typically not as protective as live vaccines and might require booster shots over time, according to the HHS. In contrast, the Oxford vaccine is a weakened form of a live virus, which can create long-lasting immune responses. Weakened virus vaccines tend to be riskier for people with weakened immune systems or other health problems, according to the HHS. Sinovac previously used the same technology to develop approved vaccines for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, swine flu, avian flu and the virus that causes hand, foot and mouth disease, according to STAT News.

Sinovac's vaccine, given in two doses 14 days apart, was well-tolerated and induced an immune response in participants, according to results from their phase 1/phase 2 trials published in November in The Lancet Infectious Diseases. But the number of antibodies produced in response to the vaccine was lower than the level found in patients who have recovered from COVID-19. The vaccine is being tested in phase 3 trials in Brazil, Indonesia and Turkey; the company has not yet announced results from these trials. But enough participants in the Brazil trial have now been infected with the virus to conduct the first analysis of it, Reuters reported. Results could come in early December, according to the trial organizers.

In September, Sinovac announced that their vaccine was well-tolerated among older adults and didn't cause serious adverse reactions. The phase 1/phase 2 trial involved 421 healthy volunteers between the ages of 60 and 89; these participants developed antibody levels comparable to the adult group ages 18 to 59, according to the statement. The vaccine protected rhesus macaque monkeys from infection with the novel coronavirus, according to a study published July 3 in the journal Science.

China has approved this vaccine for emergency use (along with two other vaccines developed by Sinopharm). About 90% of Sinovac's employees and their families have taken the experimental vaccine under China's emergency use program, Reuters reported on Sept. 6.

Moderna/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

This candidate vaccine (mRNA-1273), developed by U.S. biotech company Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), was the first to be tested on humans in the U.S., according to a previous Live Science report. It's also one of the first to release early results from its phase 3 trial.

An analysis of the early data suggested that Moderna's vaccine is 94.5% effective in protecting against COVID-19, the company announced on Nov. 16. The analysis was based on 95 participants in Moderna's phase 3 trial who developed COVID-19; 90 of them received a placebo and five received the vaccine. What's more, 15 of those who developed COVID-19 were people who were at least 65 years old and 20 were from diverse communities. Among the participants, 11 had severe cases of COVID-19, but none of these severe cases were among those given the actual vaccine, Live Science reported.

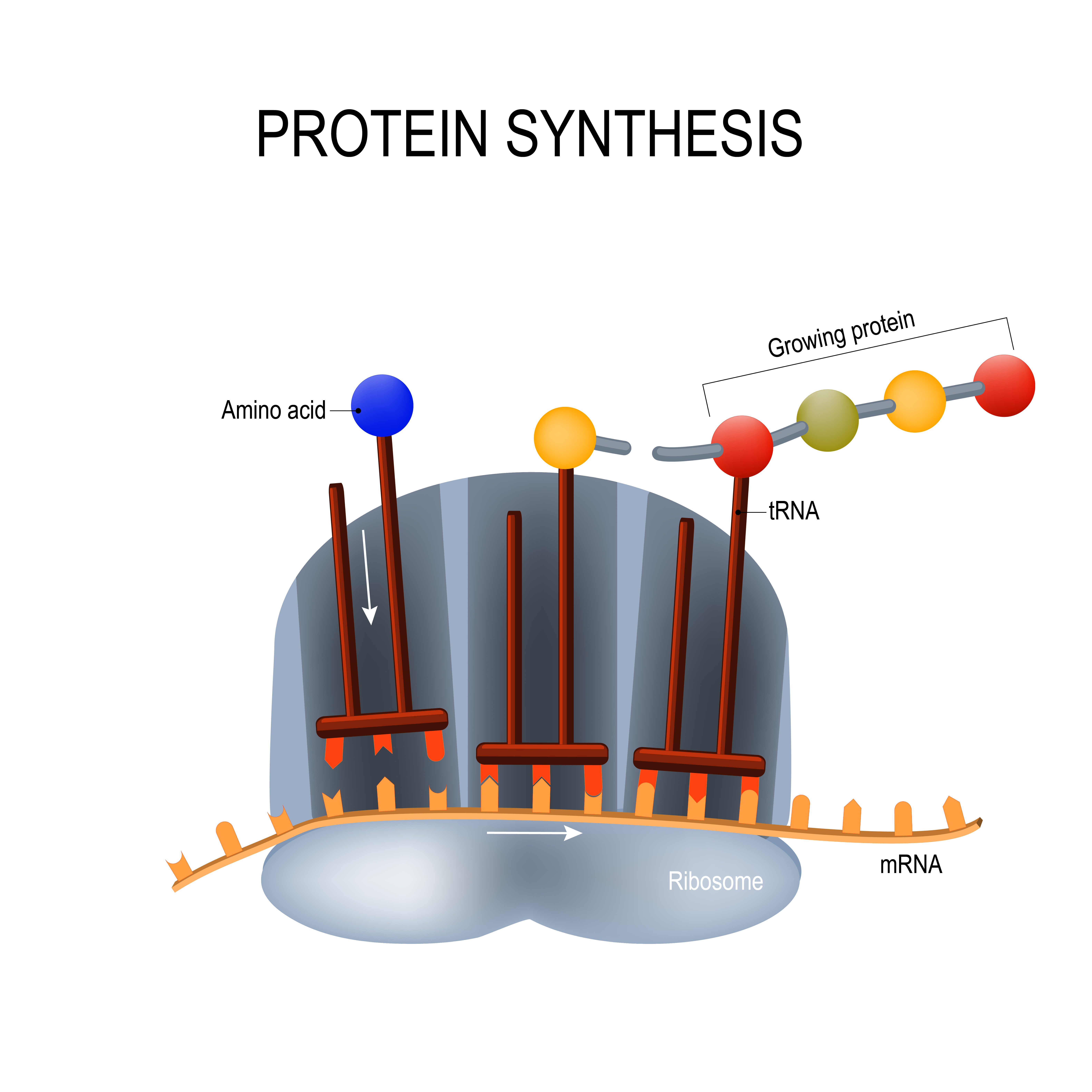

Moderna's vaccine relies on a technology that hasn't been used in any approved vaccines to date: a piece of genetic material called messenger RNA (mRNA). Traditional vaccines are made up of weakened or inactive viruses, or proteins of those viruses, to trigger an immune response; mRNA vaccines, on the other hand, are made up of genetic material that teaches cells to build these viral proteins themselves (in this case, the coronavirus' spike protein). Both traditional and mRNA vaccines trigger an immune response in the body such that if a person is naturally exposed to the virus, the body can quickly recognize and fight it.

These mRNA vaccines have several advantages, including being quicker and easier to manufacture than traditional vaccines, which can take time to develop because scientists have to grow and inactivate entire pathogens or their proteins, according to National Geographic. mRNA vaccines might also be more durable against pathogens that tend to mutate, such as coronaviruses and flu viruses. However, mRNA vaccines can cause adverse reactions in the body; these types of vaccines also have problems with stability, breaking down quite quickly, which might limit the strength of immunity, according to National Geographic.

mRNA vaccines have shown to be "a promising alternative" to traditional vaccines, but "their application has until recently been restricted by the instability and inefficient" delivery into the body, a group of researchers reported in a 2018 review published in the journal Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. "Recent technological advances have now largely overcome these issues, and multiple mRNA vaccine platforms against infectious diseases and several types of cancer have demonstrated encouraging results in both animal models and humans."

On July 14, Moderna published promising early results from a phase 1 trial consisting of 45 participants in The New England Journal of Medicine. Participants were divided into three groups and given a low, medium or high dose of the vaccine. After receiving two doses of the vaccine, all participants developed neutralizing antibodies at levels above the average of those found in recovered COVID-19 patients, Live Science reported.

The vaccine appeared safe and generally well-tolerated, but more than half of the participants had some side effects (similar to side effects that can happen from the annual flu shot) including fatigue, chills, headache, muscle aches and pain at the injection site. Some participants in the middle- and high-dose groups experienced a fever after the second injection. One person who received the highest dose experienced a "severe" fever, nausea, lightheadedness and an episode of fainting, according to the report. But this participant felt better after a day and a half. Such high doses won't be given to participants in upcoming trials.

On July 28, scientists published a new study in The New England Journal of Medicine detailing how Moderna's vaccine induced a strong immune response in rhesus macaque monkeys. After being given a 10 or 100 μg dose of the vaccine and then a second dose two weeks later (some were not given a vaccine and served as a comparison point), the monkeys were "challenged" or exposed to the coronavirus at week 8. The researchers found that the monkeys developed a strong immune response to the virus, as their immune systems produced both neutralizing antibodies and T cells. Two days after the monkeys were exposed to the coronavirus, the researchers could not detect any viral replication in the nose or lungs, suggesting that the vaccine protected against early infection. (This is in contrast to the University of Oxford study conducted in monkeys, which seemed to prevent the monkeys from developing pneumonia, but didn't prevent them from getting infected with the novel coronavirus.)

The government's Operation Warp Speed gave Moderna $955 million for research and development of its vaccine. Moderna's phase 3 trial is still ongoing, and the company expects to produce 500 million to 1 billion doses globally in 2021. The company expects to submit for an emergency use authorization (EUA) soon.

Pfizer/BioNTech

Pfizer and German biotechnology company BioNTech have, like Moderna, developed a vaccine that uses messenger RNA to prompt the immune system to recognize the coronavirus. A final analysis of their phase 3 data suggested that their vaccine is 95% effective at preventing COVID-19, the companies announced on Nov. 18. The companies became the first to submit a request for emergency use authorization on Nov. 20. The first doses of this vaccine will likely be given in December.

Pfizer and BioNTech plan to produce up to 50 million doses of its vaccine globally in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses of its vaccine by the end of 2021, according to the statement. The phase 3 trial, that began in late July, will continue for another two years and safety and efficacy data will continue to be collected, Live Science reported.

Moderna's and Pfizer's vaccines are made using the same technology, are both given in two doses and have shown to be similar in efficacy and safety. The U.S. government has promised to buy millions of doses of both vaccines if they are approved. But Pfizer's vaccine has an added difficulty: it must be stored in ultra-cold temperatures of minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 70 degrees Celsius), whereas Moderna's needs to be stored at minus 4 F (minus 20 C). Pfizer didn't take any money from the government for research and development for its vaccine, whereas Moderna did. The Pfizer vaccine didn't cause any serious adverse events and led to an immune response, according to phase 1/phase 2 data published in the journal Nature in August.. The study involved 45 patients who were given one of three doses of either the candidate vaccine or a placebo. None of the patients had serious side effects, but some developed side effects such as fevers (75% in the highest dose group), fatigue, headaches, chills, muscle pains and joint pain.

The researchers found that the vaccine prompted the immune system to make neutralizing antibodies at levels 1.8 to 2.8 times higher than those found in recovered patients, according to the study. This vaccine also prompted the body to produce T cells and other molecules to help fight the virus, according to results from another phase 1/phase 2 trial that were published in the journal Nature at the end of September. In October, Pfizer and BioNTech received FDA approval to start enrolling children 12 years old and older in its trials, according to NPR.

CanSino Biologics/Beijing Institute of Biotechnology

CanSino Biologics, in collaboration with the Beijing Institute of Biotechnology, developed a candidate vaccine (Ad5-nCoV or Convidecia) using a weakened adenovirus. Unlike the Oxford vaccine, which relies on an adenovirus that infects chimpanzees, CanSino Biologics is using an adenovirus that infects humans.

Along with Moderna, this group also published results from their phase 2 trial on July 20 in the journal The Lancet. The trial, which was conducted in Wuhan (where the first coronavirus cases emerged), involved 508 participants who were randomly assigned to receive either one of two different doses of the vaccine or a placebo. This study also didn't find serious adverse events, though some reported mild or moderate reactions including fever, fatigue and injection site pain. Around 90% of the participants developed T-cell responses and about 85% developed neutralizing antibodies, according to the study.

"The results of both studies augur well for phase 3 trials, where the vaccines must be tested on much larger populations of participants to assess their efficacy and safety," Naor Bar-Zeev and William J Moss, both part of John Hopkins' International Vaccine Access Center, wrote in an accompanying commentary in The Lancet referring to this study and the Oxford vaccine study published in the same journal. "Overall, the results of both trials are broadly similar and promising."

In June, CanSino's coronavirus vaccine was given approval to be used in China's military, according to Reuters. CanSino announced on Nov. 21 that they will start phase 3 trials of its vaccine in Argentina and Chile, Reuters reported. They are already conducting phase 3 trials in Pakistan, Russia and Mexico.

Gamaleya Research Center (Sputnik V)

The Russia Ministry of Health's Gamaleya Research Institute has developed a coronavirus vaccine candidate, now known as "Sputnik V," based on two different adenoviruses, or common cold viruses that infect humans. These viruses are genetically altered to not replicate in humans and to code for the coronavirus's spike protein.

Russia announced on Nov. 24 that its vaccine was more than 91.4% effective in preventing COVID-19, according to results from a second analysis of its phase 3 trial. The analysis was based on 39 participants who either received a placebo or the Sputnik V vaccine and later went on to develop COVID-19 (Their results agreed with their first analysis of their phase 3 data based on 20 participants). But the vaccine makers also said that an early analysis of an unspecified, smaller subset of the participants suggested that their vaccine was actually 95% effective in preventing COVID-19 three weeks after participants received the second dose. The researchers said they will do another analysis once 78 of the trial participants become infected with COVID-19. But some experts were skeptical about the 95% figure because it was based on incomplete data, according to The New York Times.

In August, President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia approved the vaccine for use in tens of thousands of people, before it was thoroughly tested in late-stage clinical trials, drawing international criticism, Live Science previously reported. But the registration certificate issued by Russia's Ministry of Health showed that the vaccine was only approved for use in a small group of people, including health care workers, according to Science Magazine.

In September, the researchers published results from their phase 1/phase 2 trials in the journal The Lancet. The analysis, based on 76 participants (none of whom were given a placebo), suggested their vaccine was "safe and well tolerated." Most adverse events were mild, none of the participants had serious adverse events and the participants developed higher antibody levels against the coronavirus than people who have recovered from COVID-19.

Adenoviruses have been used to make vaccines for decades, and an adenovirus is also the base of the coronavirus vaccines developed by Johnson & Johnson's Janssen Pharmaceutical companies, China's CanSino Biologics and the University of Oxford.

"The uniqueness of the Russian vaccine lies in the use of two different human adenoviral vectors which allows for a stronger and longer-term immune response as compared to the vaccines using one and the same vector for two doses," according to the statement. After the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca announced that two full doses of the same adenovirus led to a 62% efficacy, the Sputnik V researchers tweeted: "Sputnik V is happy to share one of its two human adenoviral vectors with @AstraZeneca to increase the efficacy of AstraZeneca vaccine. Using two different vectors for two vaccine shots will result in higher efficacy than using the same vector for two shots."

Sinopharm

The state-owned China National Pharmaceutical Group (Sinopharm)'s candidate vaccine is an inactivated form of SARS-CoV-2. On Aug. 13, the company published data from its phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials in the journal JAMA. In the phase 1 trial, 96 healthy adults were randomly assigned to receive either a low, medium or high dose of the vaccine or to receive aluminum hydroxide as a placebo. They were given second and third doses of the vaccine (or the placebo) after 28 days and 56 days, respectively.

The researchers found that the vaccine triggered their bodies to produce neutralizing antibodies. In the participants who received the placebo, 12.5% had adverse reactions. In those who received low, medium and high dose vaccines, 20.8%, 16.7% and 25% had mild adverse reactions, respectively, according to the study. In the phase 2 trial, 224 adults were given a medium dose or a placebo and then a second shot either 14 days or 21 days after the first. Again, the participants developed neutralizing antibodies and reported some mild adverse reactions. The most common adverse reaction was pain at the injection site, and then mild fever. "No serious adverse reactions were noted," the authors wrote.

The company has already begun its phase 3 trial in Abu Dhabi, which will recruit up to 15,000 people, according to Reuters. The participants will receive one of two vaccine strains or a placebo, according to Reuters. The company also launched phase 3 trials in Peru and Morocco, according to Reuters. Sinopharm is testing a second vaccine developed by the Beijing Institute of Biological Products in a phase 3 trial in the United Arab Emirates and Argentina.

Almost 1 million people have already been given Sinopharm's vaccine in China under an emergency use program, according to CNN. The vaccine was given to construction workers, diplomats and students who have since traveled to 150 countries across the globe without reporting an infection, Sinopharm Chairman Liu Jingzhen said in an article on social media platform WeChat, according to CNN. No serious adverse effects have been reported, according to the article.

The United Arab Emirates granted emergency approval on Sept. 14 for Sinopharm's coronavirus vaccine for frontline health care workers, according to Reuters.

Johnson & Johnson's Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies

Johnson & Johnson's Janssen experimental COVID-19 vaccine, is also based on a weakened adenovirus (ad26) and is given to volunteers as a single dose (most of the other candidate vaccines are given in two doses). Again, this type of vaccine, called a vector-based vaccine, uses a weakened virus (a vector) to deliver "information" about the pathogen to the body to spur the immune response. Just as with other adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccines, the weakened adenovirus expresses the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Janssen is using the same technology it used to develop its Ebola vaccine.

The U.S. government's Operation Warp Speed has funded $456 million for the development of this vaccine. Johnson & Johnson also announced a $1 billion agreement with the U.S. government to deliver 100 million doses of the vaccine in the U.S. if it receives approval or emergency use authorization from the FDA.

Johnson & Johnson began phase 3 trials in the U.S. on Sept. 23. The company has not yet released data from these trials. In October, the company paused its trials (this is common in clinical trials) after a participant developed an unexplained illness, but then resumed in the U.S. after a "thorough evaluation" didn't find a clear cause for the illness, according to a statement. "There are many possible factors that could have caused the event. Based on the information gathered to date and the input of independent experts, the Company has found no evidence that the vaccine candidate caused the event," the company wrote in the statement. But discussions with global regulatory agencies to resume trials in other countries are still continuing. On Nov. 15, Johnson & Johnson announced the start of a new global phase 3 trial that will study the safety and efficacy of two doses of the vaccine (rather than one).

Both phase 3 trials follow "positive interim results," regarding safety and efficacy from the phase 1/phase 2 clinical trial, which has been posted to the preprint site medRxiv and hasn't yet been peer-reviewed. Almost all of the participants developed a strong T cell response and antibodies to the virus, including neutralizing antibodies, after a single dose. The trials are ongoing and they are also testing the effect of a vaccine when given as two doses. The majority of adverse events were "mild and moderate," according to a statement. However, two adverse events were reported in the trials, the first event was found not to be related to the vaccine and the second was in a participant who developed a fever and was hospitalized with "suspicion" that they had COVID-19 but recovered in 12 hours, according to the statement.

Researchers reported on July 30 in the journal Nature that a single shot of the Ad26 vaccine protected rhesus macaques from infection with SARS-CoV-2. In this study, the scientists tested seven slightly varying types of Ad26 vaccine prototypes and identified the one that produced the highest number of neutralizing antibodies. After receiving the chosen variant, the monkeys were then exposed to the coronavirus. Six out of seven monkeys that were given this prototype vaccine, calledAd26.COV2.S, and then exposed to the coronavirus showed no detectable virus in the lower respiratory tract and one showed very low levels in the nose, according to a statement.

Novavax

U.S.-based vaccine development company Novavax has developed and is testing a candidate coronavirus vaccine called NVX-CoV2373. Called a "recombinant nanoparticle vaccine," it's made up of several SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins that are combined in a nanoparticle along with an immune-boosting compound called an adjuvant, according to The New York Times.

The company, which has not brought a vaccine to market in it's 33-year-history, has made a $1.6 billion deal with the U.S. government under Operation Warp Speed, according to the Times. On Sept. 2, early, promising results from Novavax's phase 1/phase 2 trials were published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The trials involved 131 healthy adults: eighty-three of the participants received the vaccine with the adjuvant; 25 received the vaccine without the adjuvant; and 23 received the placebo. The participants were given two doses of the vaccine 21 days apart. "No serious adverse events were noted," the researchers wrote. One participant had a mild fever that lasted for a day, according to the paper.

Thirty-five days after the initial dose, participants who received the vaccine had immune responses that exceeded those in patients who recovered from COVID-19. All of the participants developed neutralizing antibodies at levels of four to six times greater than the average developed by recovered patients, according to CNN. In 16 participants, who were randomly tested, the vaccine seemed to generate T-cell responses (T cells are a group of white blood cells important in the fight against pathogens). "The addition of adjuvant resulted in enhanced immune responses," the authors wrote.

Based on these safety results from phase 1, the company has begun the phase 2 trial of the study. The company has also begun a separate phase 2 study in South Africa, testing their candidate COVID-19 vaccine on both HIV-negative and HIV-positive volunteers. On Sept. 24, Novavax announced that it started its phase 3 testing of the vaccine in the United Kingdom and will enroll up to 10,000 volunteers.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.