Monstrous 'murder hornets' have reached the US

Native to Asia, the giant insects rip off the heads of honeybees by the thousands.

Massive, deadly hornets affectionately known as "murder hornets" "hornets from hell" and "yak-killer hornets," have been spotted in the U.S. for the first time.

These Asian giant hornets (Vespa mandarinia) are the size of your thumb; they're orange-headed and orange-striped; and they're extremely pointy at the back end. The hornets, which were detected in Washington state, prey on bees and are known for ripping the heads off honeybees by the thousands, The New York Times reported on May 2. Enormous curved stingers and powerful venom make the hornets uniquely dangerous to humans, and their stings are responsible for as many as 50 deaths in Japan each year, mostly due to allergic reactions to the venom, according to the Times.

V. mandarinia is native to forests and low-altitude mountains in eastern and southeastern Asia, but troubling evidence suggests that the hornet is beginning to make some headway in North America. Now entomologists are racing against the clock to learn how widespread the invaders are in the U.S., and to isolate and destroy invasive populations before the hornets become so numerous that they settle in for good, the Times reported.

Related: Sting, bite & destroy: Nature's 10 biggest pests

The Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) verified two sightings of Asian giant hornets in early December 2019, Washington State University (WSU) Insider reported on April 6. WSDA received two more accounts describing the invasive insects, but those remain unconfirmed. No one knows how the hornets arrived in the U.S., but they may have been introduced as other types of invasive insects have: They were deliberately released, or transported here as unseen stowaways in international cargo, WSU representatives said in a statement.

Hornets are large members of the wasp family, and Asian giant hornets are the biggest hornets in the world, according to Animal Diversity Web (ADW), a database maintained by the University of Michigan's Museum of Zoology. Queens can grow to be 2 inches (5 centimeters) in length, with a wingspan of more than 3 inches (8 cm), while female workers and males are somewhat smaller, with body lengths of about 1 to 1.5 inches (3.5 to 3.9 cm).

Only the females of the species have stingers, which can measure up to 0.2 inches (6 millimeters) long; the stingers can be used repeatedly; and they deliver a toxin that is "considerably venomous," ADW says. The pain from their sting is significant, "like a hot nail through my leg," Masato Ono, an entomologist at Tamagawa University near Tokyo, told National Geographic in 2002.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These so-called killer hornets made headlines worldwide in 2013, when a series of attacks in China injured hundreds of people and killed 28, mostly in Shaanxi province, Live Science previously reported.

However, not all people shy away from the hornets. In some Japanese mountain villages, the hornets are considered a delicacy when deep fried, according to the BBC.

Hunt, slaughter, occupy

European honeybees have the most to fear from this deadly predator. V. mandarinia are social hornets, and they are the only known wasp species to coordinate attacks on bee colonies, which they carry out with deadly precision.

Attacks on beehives happen in three phases, ADW says. First, the hornets hunt individual bees from a hive that has been chemically marked by one of their sisters. The hornets rip the bees to pieces, carrying the dismembered bits back to their own hive and feeding them to hornet larvae.

Next is the slaughter phase, when dozens of hornets attack the hive and massacre tens of thousands of bees.

"Within a few hours, a strong, healthy and populous honey bee colony of 30,000 to 50,000 workers is slaughtered by a group of 15 to 30 hornets," according to a WSU fact sheet.

Finally, the hornets move into the defeated hive. They chew up the abandoned bee larvae and pupae into a bee-brood paste, which the hornets also feed to their own young. During this stage, the hornets are especially aggressive and may attack animals and humans that are unfortunate enough to wander too close to the occupied beehive, WSU says.

"Hot defensive bee balls"

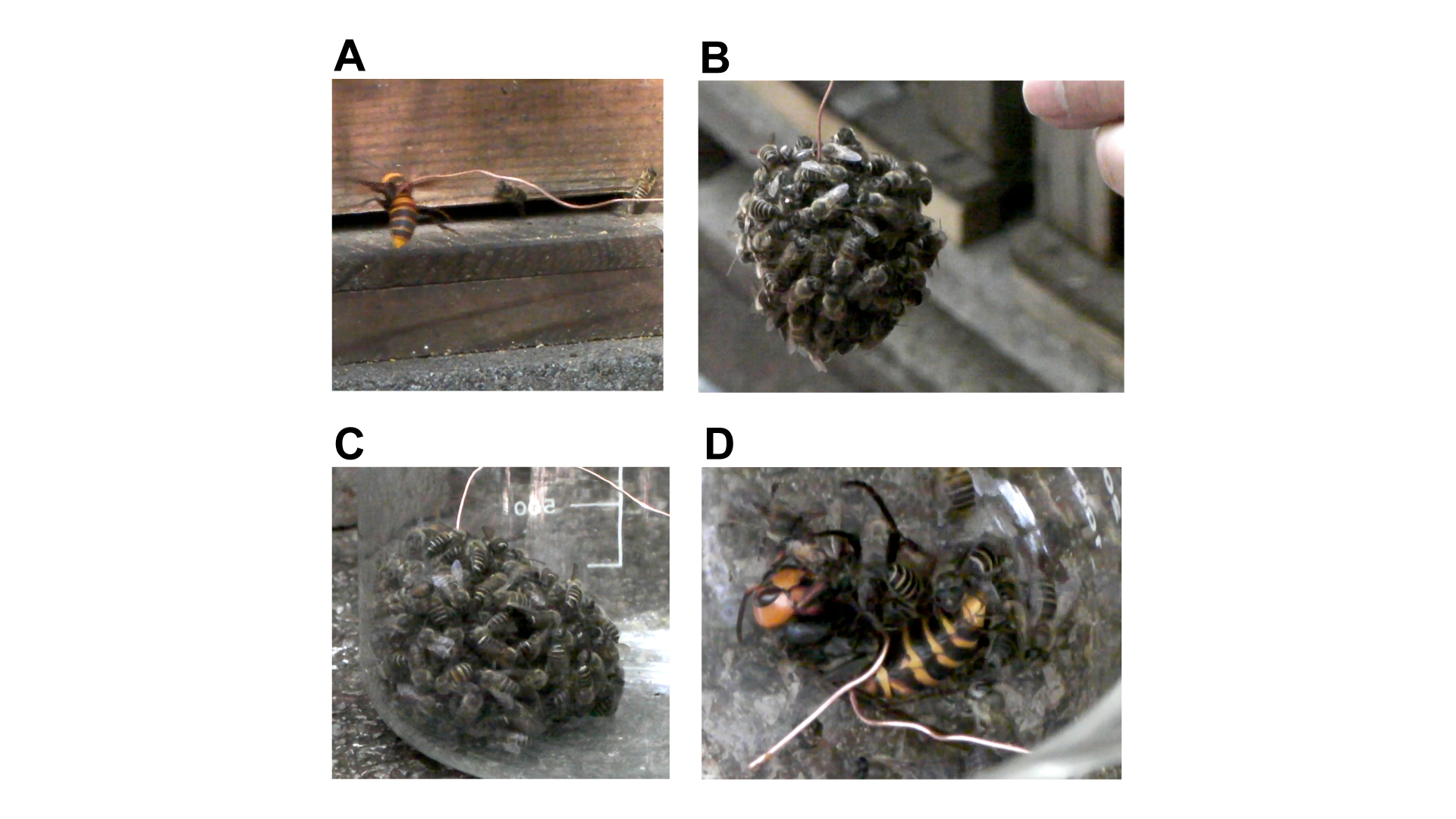

European honeybees (Apis mellifera ligustica) are powerless against giant hornet attacks, but Japanese honeybees (Apis cerana japonica) have evolved a unique defense against the marauding hornets. They form "hot defensive bee balls," swarming individual hornets and vibrating their flight muscles to generate heat. Inside the ball, temperatures build to 116 degrees Fahrenheit (47 degrees Celsius), cooking the trapped hornets to death.

Japanese honeybees are the only bee species with special brain cells that allow them to collectively thermoregulate just enough heat to kill the hornets without hurting themselves, Live Science previously reported.

Giant hornets from Asia made their first forays into North America in Canada, with sightings of three V. mandarinia hornets reported on British Columbia's Vancouver Island in mid-August 2019, according to British Columbia's Ministry of Agriculture. The agency issued a pest alert for the invasive hornets in September 2019, warning that more hornets might be seen in the spring when queens emerge from hibernation and establish their annual nests.

Springtime is also when Asian giant hornets are likely to become active in Washington State, entomologists told WSU Insider.

Conditions in the Pacific Northwest are just right for Asian giant hornets, according to a fact sheet issued by WSU. Should the Asian giant hornet become established in the U.S., its impact on native bee populations would be "severe enough to cause significant disruptions," WSU associate professor Timothy Lawrence said in a statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.