Ancient remains found in Indonesia belong to a vanished human lineage

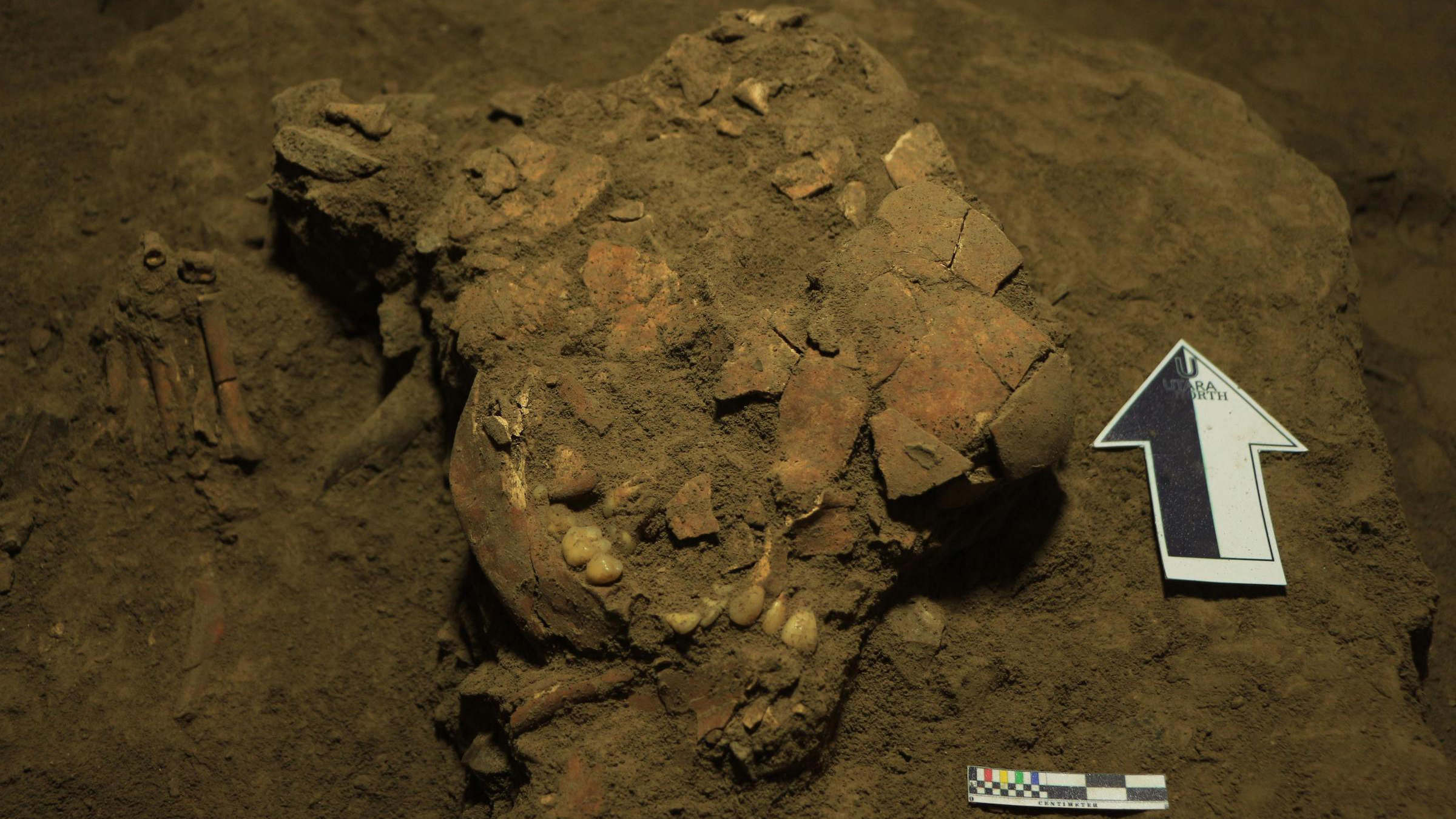

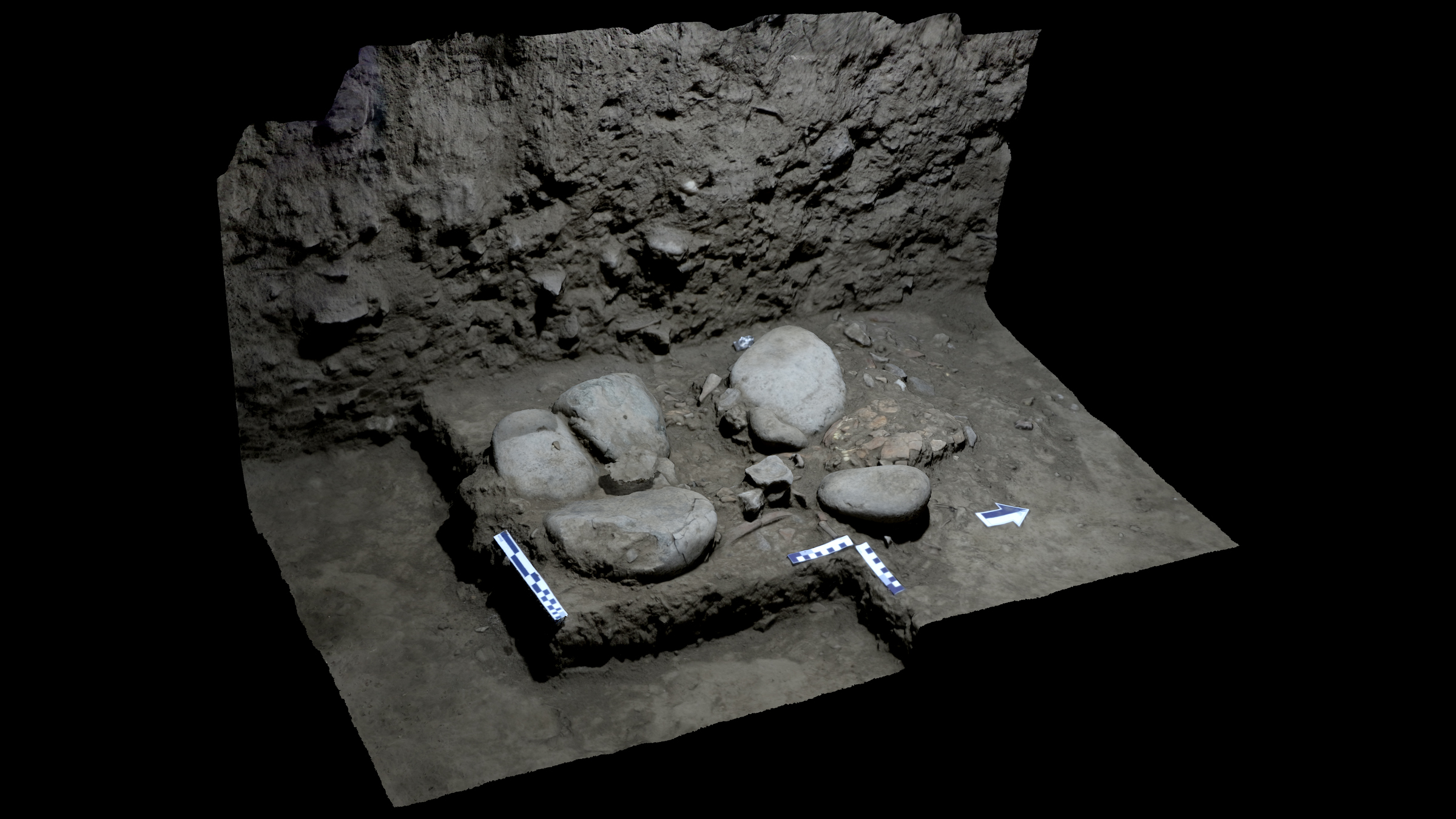

The 7,200-year-old burial was found in a cave.

A woman buried 7,200 years ago in what is now Indonesia belonged to a previously unknown human lineage that doesn't exist anymore, a new genetic analysis reveals.

The ancient woman's genome also revealed that she is a distant relative of present-day Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians, or the Indigenous people on the islands of New Guinea and the western Pacific whose ancestors were the first humans to reach Oceania, the researchers found.

Like the Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans, the woman had a significant proportion of DNA from an archaic human species known as the Denisovans, the researchers found. That's in sharp contrast with other ancient hunter-gatherers from Southeast Asia, such as in Laos and Malaysia, who do not have much Denisovan ancestry, said study co-leader Cosimo Posth, a professor at the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

These genetic discoveries suggest that Indonesia and the surrounding islands, an area known as Wallacea, was "indeed the meeting point for the major admixture [mating] event between Denisovans and modern humans on their initial journey to Oceania," Posth told Live Science in an email.

Related: Denisovan gallery: Tracing the genetics of human ancestors

Researchers have long been interested in Wallacea. It's estimated that ancient humans traveled through Wallacea at least 50,000 years ago (possibly even before 65,000 years ago) before they reached Australia and its surrounding islands.

Researchers found the mysterious woman's burial in Leang Panninge cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi in 2015. "This was an exciting discovery, as it was the first time a relatively complete set of human skeletal remains had been found in association with artifacts of the 'Toalean' culture, enigmatic hunter-gatherers who inhabited the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi between around 8,000 to 1,500 years ago," study co-lead researcher Adam Brumm, a professor of archaeology at Griffith University in Australia, told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To learn more about this woman — who died at about age 18, an anatomical analysis revealed — the researchers studied her ancient DNA, which was still preserved in her inner ear bone. "This is a major technological achievement, as we all know ancient DNA does not preserve well in tropical regions," said Serena Tucci, an assistant professor of anthropology at Yale University and principal investigator of the Human Evolutionary Genomics lab there, who was not involved in the new study. "Only a few years ago we didn't even imagine this could be feasible."

The analysis marked the first time researchers have studied an ancient human genome in Wallacea, the researchers added.

The woman's genome showed that she was equally related to present-day Aboriginal Australians and Papuans, Posth said. "However, her particular lineage split off from these populations at an early point of time," Brumm noted.

Moreover, this woman's lineage doesn't appear to exist today, making it a "previously unknown divergent human lineage," the researchers wrote in the study. In other words, this ancient Toalean woman has a genome "that is unlike that of any modern people or groups that are known from the ancient past," Brumm said.

As such, the researchers found no evidence that the modern people of Sulawesi descend from the Toalean hunter-gatherers, at least based on the genome of this woman.

Perhaps this Toalean woman carried a local ancestry from ancient people who lived on Sulawesi before Australia and its surrounding islands were populated, the researchers said.

In all, the study is "very exciting and fascinating," Tucci told Live Science in an email.

"We are learning that there was a previously unknown population that migrated throughout this region, probably at about the same time as the ancestors of present day populations in Papua or Australia," she said. Even though this woman's lineage disappeared, "all these populations did coexist until relatively recently, which opens up to lots of questions about population interactions from a genetic but also from a cultural perspective," Tucci said.

The study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 25) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.