Mysterious Megastructures of the Elusive Tripolye Culture Unearthed in Ukraine

The settlement fell some 5,000 years ago.

The excavation of a Stone Age community center in Ukraine is helping explain why large groups of tens of thousands of people flourished and then fell more than 5,000 years ago.

The "megastructure" excavated in Ukraine was large compared with the houses around it, though not particularly huge by modern standards. At 2,045 square feet (190 square meters), the structure was the size of a modest American home. However, some Eastern European megastructures were up to 18,000 square feet (1,680 square m) in size. Archaeologists have puzzled over these buildings, many of which have been discovered through methods that use magnetic anomalies in the soil to detect ancient structures. Now, the actual excavation of this one megastructure at a site called Maidanetske reveals that these buildings were used for everyday activities, like food preparation, storage and meals.

"It is similar to activities performed in normal houses," said Robert Hofmann, an archaeologist at Christian-Albrechts University in Kiel, Germany, who led the new research. "Somehow the intensity of these activities between normal houses and these megastructures is completely different."

Related: Back to the Stone Age - 17 Key Milestones in Paleolithic Life

Tripolye culture

The megastructures were constructed by the Tripolye culture, a civilization that stretched from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dnieper River during the Stone Age. From about 4100 B.C. to 3600 B.C., the Tripolye people built large communities called megasites, which consisted of thousands of houses. Maidanetske, in modern-day Ukraine, had 3,000 individual homes, though it's not clear if they all existed at the same time or if there were phases of demolishing and rebuilding. Thus, the population of these communities tends to be hard to pin down, Hofmann told Live Science. Maidanetske may have been home to as few as 5,000 people or as many as 15,000, he said.

Related: In Photos: Prehistoric Temple Uncovered in Ukraine

Archaeologists also debate whether the megasites were year-round settlements or seasonal gathering spots. The Tripolye people were farmers who cultivated cereal grains, Hofmann said, as well as herders who traded mainly in cattle. They hunted wild game as well, though evidence for hunting declines over time, such that domesticated animals were more often used for food during the era of the megasites. (Some scientists believe the wheel originated with the Tripolye culture.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

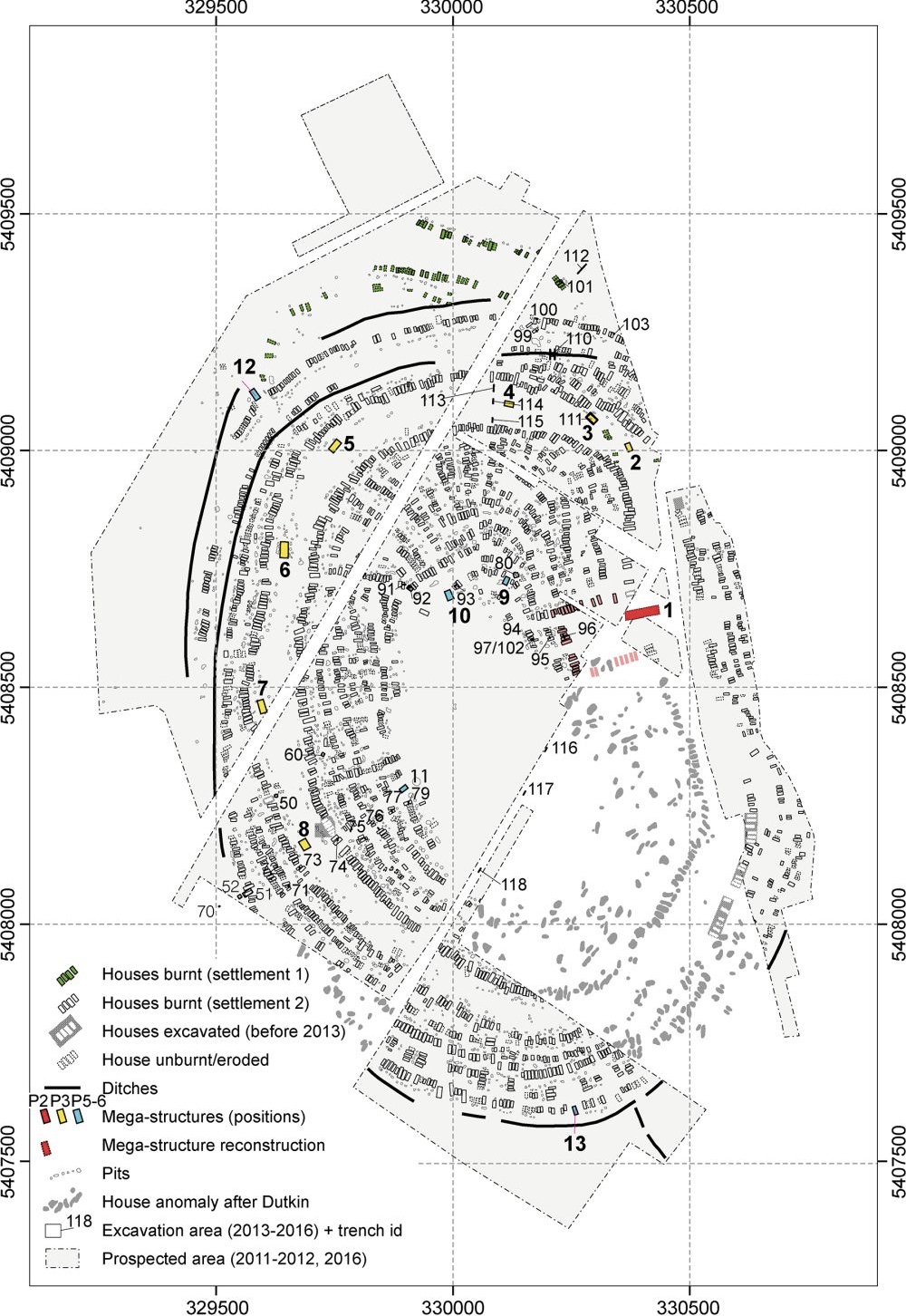

The houses in Tripolye megasites were typically arranged in concentric circles, occasionally dotted with plazas anchored by the large rectangular buildings that archaeologists have dubbed "megastructures." Hofmann and his colleagues compared their Maidanetske excavations with magnetic and archaeological data from 12 other megastructures in Maidanetske and 104 others from 19 different sites across Eastern Europe.

Food and feasts

The Maidanetske megastructure consisted of one roofed-in section and one slightly larger open-air walled courtyard. It dated to the 38th century B.C., the researchers report today (Sept. 25) in the open-access journal PLOS ONE. The walls were made of clay-covered split wood and logs, and a raised fireplace sat in the enclosed part of the building.

Scattered throughout the structure, the archaeologists found pottery , including sealed jars and kitchenware. There were also bones scattered near the fireplace, presumably from a last meal before the building was abandoned. (Most waste went into a pit, or midden, near the building.) Archaeologists also found other flotsam of everyday life: a polishing stone, a whetstone and a loom weight.

The building was very different from the houses at the time, which had a smaller footprint, were 2 stories tall and always contained both a fireplace and an oven, Hofmann said. By mapping out the locations of megastructures in different Tripolye settlements, the researchers found that the buildings were strategically placed. Smaller ones were found around peripheral rings in the settlements, while larger ones were in more central spots. It seemed that there may have been different levels of assembly places for different segments of society, Hofmann said.

Over time, he said, the smaller megastructures disappeared from the settlements, leaving only the largest in use. This change may provide some hint of centralization — and that centralization may have eventually spelled doom for Tripolye's big-city ways. Between 3650 B.C. and 3500 B.C., the megasites dissolved, and the people of the Tripolye culture returned to living in smaller villages. The lack of low-level assembly places before this change might indicate that ordinary people became less and less involved in the government of the community, ultimately leading to its dissolution.

The researchers are now trying to get a better sense of how megastructures differed from region to region and how they were used on a daily basis. Hofmann's team just excavated a trash pit from a megastructure in Moldova, and they are working to compare the contents of the pit with the content of waste pits from normal houses.

"We can already feel differences," he said, "but we need quantification of different finds and closer analysis."

- 7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot

- 10 Amazing Modern Societies You Won't Believe Are Real

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality