Mysterious minimoon circling Earth is actually a 1960s rocket booster

That's no moon.

A mysterious minimoon temporarily orbiting Earth isn't a chunky space rock, but a 1960s rocket booster, NASA reported Wednesday (Dec. 2).

Researchers had an inkling that the minimoon might be human-made, but it wasn't until this week that they confirmed it, after analyzing its composition from afar at NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF).

In fact, scientists made the finding just after the elusive near-Earth object — known as 2020 SO — made its closest approach to our planet on Tuesday (Dec. 1).

Related: Top 10 ways to destroy Earth

However, 2020 SO isn't here to stay. Minimoons are small satellites that orbit Earth for only a short time. Over the next several months, 2020 SO will hang out in the "hill sphere" — a region that extends about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth — until it escapes from our gravitational force and starts orbiting the sun instead in March 2021, NASA reported in a statement.

But even though 2020 SO is leaving Earth's immediate neighborhood, scientists plan to monitor its travels for years to come, NASA said.

That's no moon

Scientists first spotted the 2020 SO in September of this year, when astronomers looking for near-Earth asteroids at Pan-STARRS1, a NASA-funded survey telescope on Maui, Hawaii, noticed its small size and unusual orbit.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They soon learned that 2020 SO wasn't a stranger to Earth; an analysis of its orbit indicated that 2020 SO had swung around our planet several times in the past few decades, even making a fairly close approach in 1966, suggesting it was a human-made object launched into space.

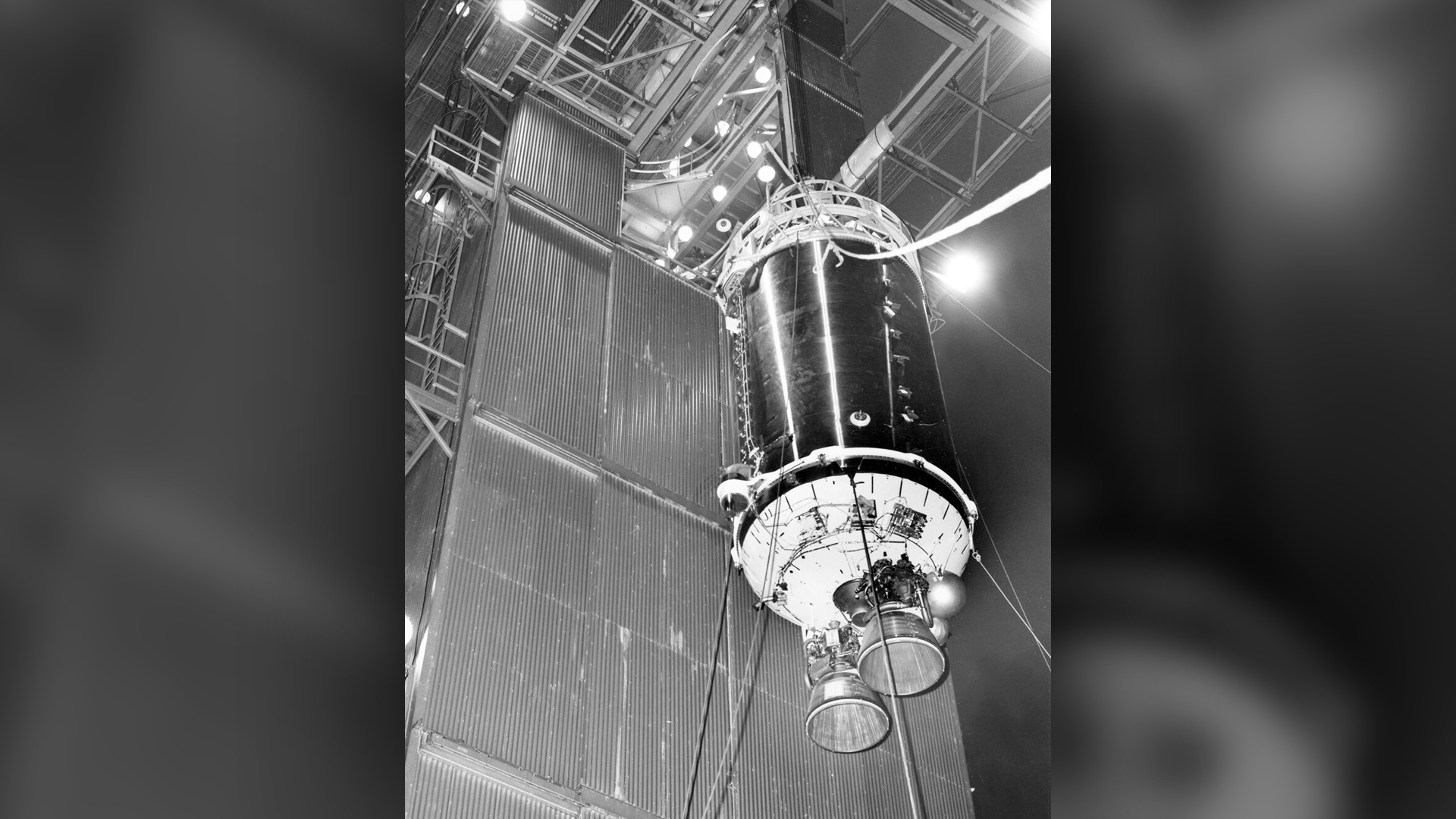

After combing through NASA's launch records, Paul Chodas, director at NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), suggested that 2020 SO was a Centaur upper stage rocket booster from Surveyor 2, an uncrewed NASA spacecraft that was supposed to softly land on the moon, but instead ended up crashing there in 1966.

To investigate this claim, a team led by Vishnu Reddy, a planetary scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, took follow-up spectroscopy observations of the object using NASA's IRTF on the Big Island of Hawaii, so they could determine the space oddity's chemical makeup. (In spectroscopy, light waves from a certain part of the electromagnetic spectrum are measured to reveal an object's makeup.)

"Due to extreme faintness of this object following [the] CNEOS prediction, it was a challenging object to characterize" Reddy said in the statement. "We got color observations with the Large Binocular Telescope, or LBT, that suggested 2020 SO was not an asteroid."

However, the team didn't have enough evidence to tie 2020 SO to Surveyor 2. So, the researchers went a step further and compared its spectral data with that of 301 stainless steel, the material in the 1960s Centaur rocket boosters. But the results weren't a perfect match, Reddy found.

The discrepancy revealed itself soon enough; Reddy's team had analyzed fresh steel in their lab, while the steel from 2020 SO had weathered the harsh conditions of space for the past 54 years, he said.

"We knew that if we wanted to compare apples to apples, we'd need to try to get spectral data from another Centaur rocket booster that had been in Earth orbit for many years to then see if it better matched 2020 SO's spectrum," Reddy said. "Because of the extreme speed at which Earth-orbiting Centaur boosters travel across the sky, we knew it would be extremely difficult to lock on with the IRTF long enough to get a solid and reliable data set."

An opportunity to finally solve the mystery happened on the morning of Dec. 1. At that time, the team managed to analyze a Centaur D rocket booster from the 1971 launch of a communication satellite that was orbiting Earth. After comparing the data from the 1971 rocket booster and 2020 SO, the team had a match.

"This conclusion was the result of a tremendous team effort," Reddy said. "We were finally able to solve this mystery because of the great work of Pan-STARRS, Paul Chodas and the team at CNEOS, LBT, IRTF, and the observations around the world."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.