Mysterious stone balls found in Neolithic tomb on remote Scottish island

Linked to unique practice in Britain.

Two polished stone balls shaped about 5,500 years ago — linked to a mysterious practice almost unique to Neolithic Britain — have been discovered in an ancient tomb on the island of Sanday, in the Orkney Islands north of mainland Scotland.

Hundreds of similar stone balls, each about the size of a baseball, have been found at Neolithic sites mainly in Scotland and the Orkney Islands, but also in England, Ireland and Norway, Live Science previously reported.

Some are ornately carved — such as the famous Towie ball discovered in northeast Scotland in 1860 — but others are studded with projections or smoothly polished.

Related: In photos: Intricately carved stone balls puzzle archaeologists

Early researchers suggested that the balls were used as weapons, and so they were sometimes called "mace heads" as a result. Another idea is that rope could have been wound around the lobes carved into some of the balls to throw them.

But most archaeologists now think the stone balls were made mainly for artistic purposes, perhaps to signify a person's status in their community or to commemorate an important phase of their lives, said archaeologist Vicki Cummings of the University of Central Lancashire in England, who led the excavations of the tomb on Sanday.

The two stone balls found at the tomb near the beach at Tresness on Sanday — one made of black stone and the other of lighter-colored limestone — are very early examples of such objects and were smoothly polished, rather than being carved like the Towie ball. Carving balls tended to happen later in the Neolithic period, she said, while polishing balls was generally an earlier practice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The two polished balls "are much simpler, but they are still beautiful objects," Cummings told Live Science. "They would have taken quite a long time to make, because it is quite time-consuming to polish a stone … You've got to sit there with some sand and some water and a stone, and basically put the work in."

Neolithic tomb

This is one of the few times that stone balls have been found in their true archaeological context, Cummings said, which could shed light on the purpose of the mysterious objects.

Each of the balls were found in the corners of two different compartments used to inter human remains in the burial chamber of the tomb, while other objects — especially pieces of pottery — were found along the compartment walls.

"Probably what was happening was that people were putting little slabs down and putting pots on top of these slabs," Cummings said. "They really seemed to be interested in the walls and the corners."

Inside the tomb, archeologists also found a deposit of cremated human bones near the entrances of two of the five compartments in the burial chamber, as well as several "scale knives," which were made by breaking beach pebbles into flakes that had a sharp edge.

"You can use it as a really good butchery tool — and we found tons of those in the [tomb], which is really surprising. And that begs the question of what they [the makers] were up to," Cummings said.

People may have used the knives to separate flesh from the bones of the dead. "It might suggest they were manipulating the human remains that were placed in the chamber — there are many traditions and lots of examples of that," she said.

Ancient islands

The Orkney Islands are beyond the very northernmost tip of mainland Scotland. They are dotted with archaeological sites, including a UNESCO World Heritage Site called the Heart of Neolithic Orkney around the Ness of Brodgar complex and the Neolithic village at Skara Brae, which suggests the islands were well-populated about 5,000 years ago.

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

"The Orkney Islands might seem remote when you look at a map, but when you come here you see they are incredibly rich agricultural land that's very easy to work," Cummings said. "I think Neolithic people got here and were really successful — they found an environment that they just thrived in."

The excavations on Sanday have been a joint effort between the University of Central Lancashire team, led by Cummings, and archaeologists from the National Museums Scotland led by Hugo Anderson-Whymark.

The ancient tomb is near the coast and is vulnerable to being disturbed by a storm at sea, so the researchers are trying to find out as much as possible before the site is damaged, Cummings said.

The tomb and a Neolithic settlement they've excavated about a mile (1.6 kilometers) away would have been farther from the coast about 5,500 years ago, and the landscape would have had more trees than it does now, she said.

Although the tomb was investigated in the 1980s, only superficial excavations were made that didn't reveal its old age.

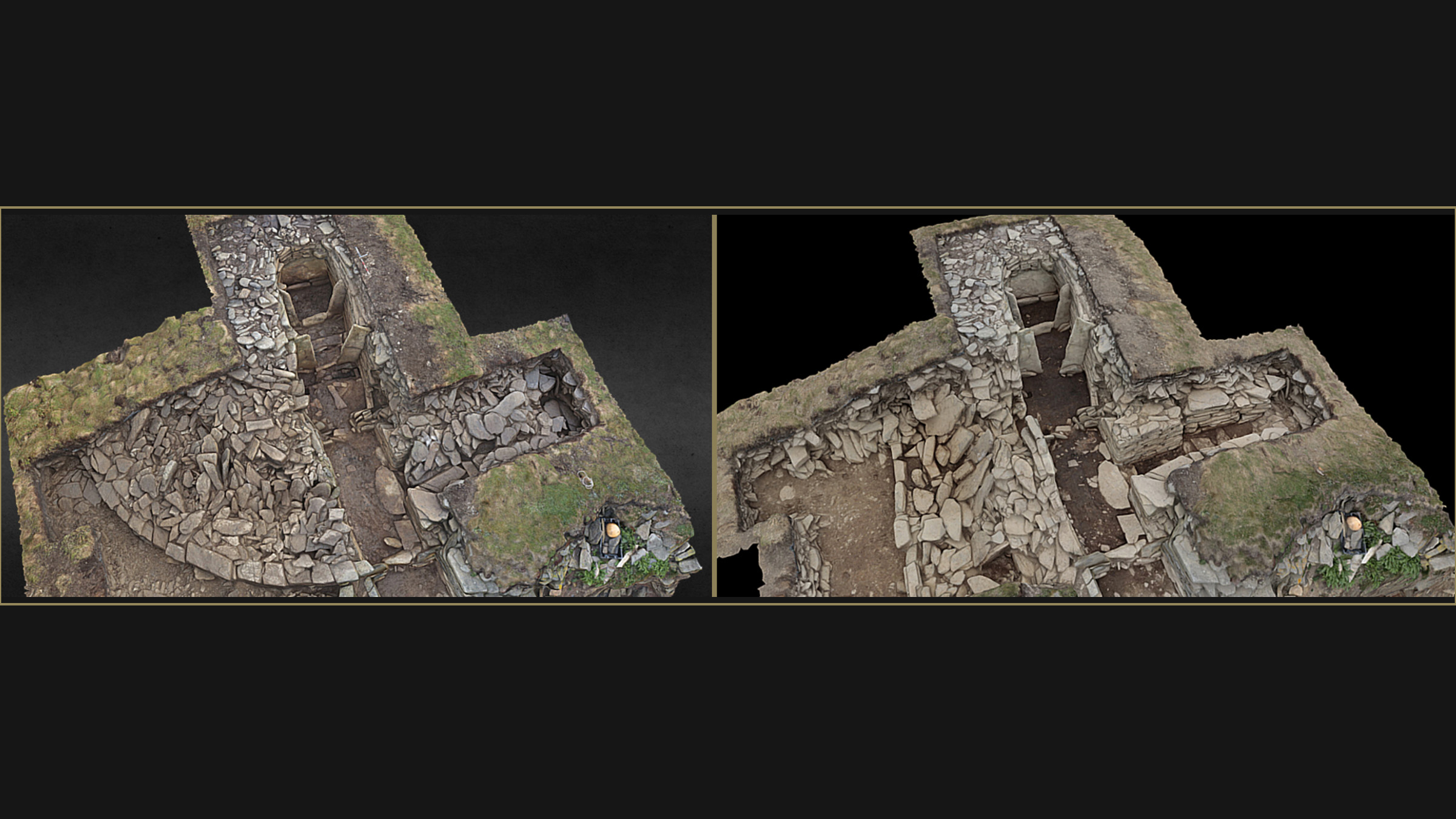

During the latest excavations, which took about four years to conclude, the researchers applied the latest archaeological techniques to the tomb, including making a three-dimensional photogrammetric model of it, Cummings said.

The archaeologists will now conduct analyses of the data gathered during the excavations, she said, which hopefully will provide even more information about the Neolithic people of the islands.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.