'Naked' shark was born without skin or teeth in world first

The skinless, three-year-old female died with an empty mouth and a full belly.

In July 2019, fishers trawling the Mediterranean Sea south of Sardinia, Italy, accidentally pulled a mutant from the depths. Ensnared in their net among hundreds of other fish, sharks and assorted marine life was a blackmouth catshark (Galeus melastomus) — seemingly born without skin or teeth.

While scientists have reported numerous cases of albinism, discoloration and other genetic skin mutations in sharks before, this rare catch is the first and only known case of a shark living with a "severe lack of all skin-related structures [including] teeth," according to a study published July 16 in the Journal of Fish Biology.

Perhaps stranger still, the abnormal shark seemed to be living a relatively normal life until it was scooped from the sea, lead study author Antonello Mulas said. When he and his colleagues examined the shark, they found that it was about 3 years old, had grown at a typical rate, and had a belly full of food when it died.

Related: Image gallery: Mysterious lives of whale sharks

"Our first reaction was, 'A shark without skin can't survive,'" Mulas, a biologist at the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, told Live Science. "But, as Shakespeare said, there are more things in heaven and Earth than you can imagine."

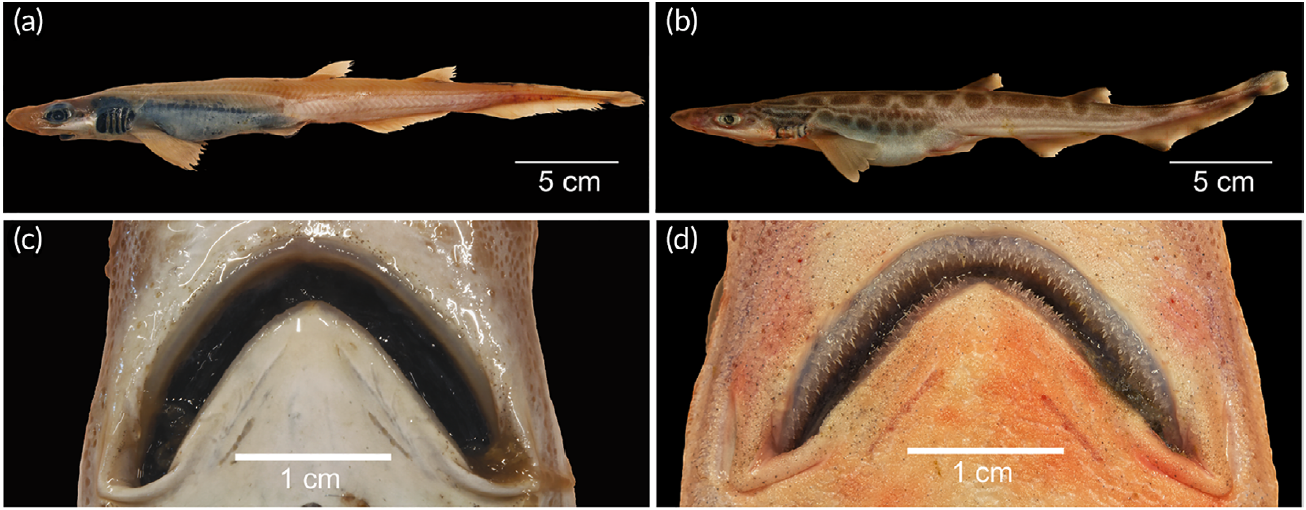

G. melastomus are common, small catsharks that can grow to a maximum length of 2.3 feet (70 centimeters) — about the size of a child's baseball bat. They are prevalent in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, where they tend to swim at depths of 650 to 1,600 feet (200 to 500 meters). True to its name, the interior of the blackmouth's maw is jet-black, as is the skin-like sheath that covers its internal organs.

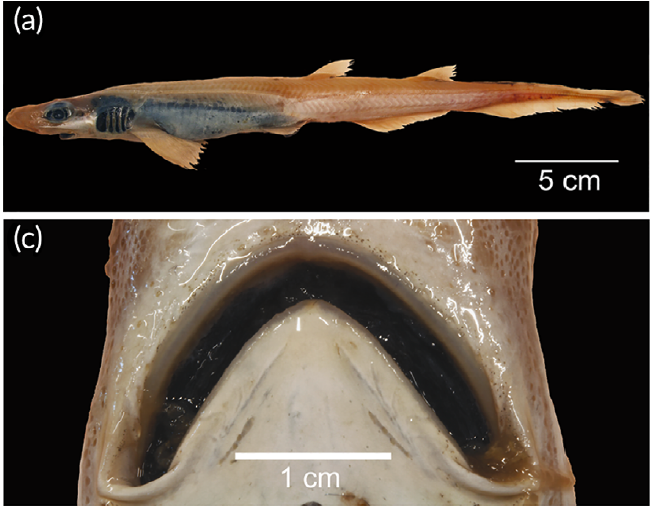

That inner blackness is plainly visible in images of the "naked shark" of Sardinia, as Mulas and his colleagues dubbed it in their paper. The shark's dark interior peeks through its gills and transparent head, sharply contrasting the rest of its wan, yellowish body. The shark looked so abnormal that the researchers' first impulse was to make sure it wasn't an "alien" — that is, a species not native to the Mediterranean, Mulas said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There are more than 300 species of shark, and we wanted to make sure this wasn't some type we'd never heard of," Mulas added.

The shark was no alien, the researchers found — just otherworldly. The team's investigation revealed that the catshark was a young female measuring 1 foot (30 cm) long, which showed normal growth for its age. Besides obviously missing its epidermis (the outermost layer of skin), the shark was also missing its dermal denticles — tiny, fang-like structures that line the skin of all sharks and rays, a microscopicy analysis revealed. These hard, pointed scales not only provide sharks with physical protection, but also make them faster, more agile swimmers, Mulas said.

In the absence of dermal denticles, the naked catshark was likely a weaker swimmer than its peers — but that apparently didn't stop it from successfully filling its stomach, nor did its lack of teeth. In the shark's gut, the researchers found 14 food items, including a buffet of tiny cephalopods, crustaceans and bony fishes. Because blackmouth catsharks typically swallow their prey whole, the naked shark's naked mouth did not make her any less effective a predator, Mulas said.

Related: The 10 weirdest medical cases in the animal kingdom

The shark's abnormal appearance was almost certainly the result of a genetic mutation, the researchers concluded. This mutation may be totally natural, or it could have been influenced by exposure to chemical pollution in the water, Mulas said. To get a better idea, the researchers will return to the site where the naked catshark was caught and sample the sediment on the seafloor. This analysis should reveal if there was anything potentially harmful in the shark's environment, and could point the way toward other similarly strange sea creatures, Mulas said.

"Maybe we'll find a two-headed shark, or Blinky [the three-eyed] 'Simpsons' fish," he said hopefully.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.