Who Was Napoleon Bonaparte?

Reference Article: Facts about Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France.

Napoleon Bonaparte rose from a family of minor nobles on the French island of Corsica to become ruler of much of continental Europe. After his 1815 defeat at the Battle of Waterloo (in what is now Belgium), he was forced into exile on the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

While Bonaparte may be known for being somewhat short — a commonly held but false myth spread by British propaganda at the time — his reach throughout history is long. For generations, historians have carried out countless historical studies on his life and empire.

Napoleon's life before the military

Born on the island of Corsica in 1769, he was christened Napoleone di Buonaparte and later changed his name to Napoleon Bonaparte when he married in 1796.

Corsica was more or less independent (Genoa controlled the island nominally) when it was conquered by France between 1768 and 1769. Napoleon's mother, Maria Letizia Buonaparte, and father, Carlo Maria di Buonaparte, were both supportive of French rule, and the family members were recognized as minor French nobles by the French government. This recognition made it easier for Bonaparte to attend military school and receive training as an artillery officer.

Bonaparte didn't become fluent in French until he attended military school in Brienne, France, from 1779-1784. After completing courses in Brienne, he attended École Militaire, a more advanced military academy in Paris. He graduated in 1785 and was commissioned as an artillery officer in the French army.

Bonaparte's rise to power

The French Revolution, which started in 1789 and led to the beheading of French King Louis XVI, created an unstable political environment in which Bonaparte could use his military prowess to rapidly rise to power.

His rise began in 1793 when a group loyal to the French monarchy captured the city of Toulon with help from the British. The republican government ordered a military expedition to retake the city, and Bonaparte served as one of the operation's senior leaders, developing a battle plan that led to the city's recapture. Then, in 1795, Bonaparte helped lead a military force that put down a rebellion in Paris.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: 10 Historically Significant Political Protests

In 1796, Bonaparte was appointed commander of French forces in Italy, and within a year, his troops had conquered much of Italy and part of Austria. The conquered territories were forced to pay money and goods to France. Bonaparte used rapid marches to outmaneuver and divide enemy forces. He positioned his soldiers strategically so that when a battle occurred, his army outnumbered the enemy force. He praised his soldiers, referring to them at times as "brothers in arms," and tried to keep their morale high.

The military success in Italy boosted Bonaparte's reputation in France, which led him to a greater position of power in France's republican government. In 1798, Bonaparte led a French military expedition to Egypt, a country controlled by the Ottoman Empire. He hoped to take Egypt and then conquer much of the Middle East.

While the expedition succeeded in taking northern Egypt, Bonaparte's forces were cut off when the British defeated a French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. This made it hard for France to send supplies and reinforcements to Bonaparte's weary troops.

The scientific component of the expedition was more successful. Bonaparte brought a large team of scientists with him who recorded a vast amount of information about Egypt's ancient monuments. Most importantly, the Rosetta Stone was discovered, a find that allowed for the decipherment of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

While Bonaparte's troops were stranded in Egypt, the situation was deteriorating for France. Austria and Russia went to war with France, joining Britain and the Ottoman Empire, and revolts broke out in France as people loyal to the French monarchy tried to overthrow the government. Taking advantage of the situation, Bonaparte left Egypt for France in 1799 and led a military coup that saw him appointed "first consul" of France.

By 1802, Bonaparte had a remarkable military record: He had put down rebellions in France, reconquered Italy and forced the other countries to sue for peace by defeating their armies on the battlefield.

Napoleon Bonaparte I, Emperor of France

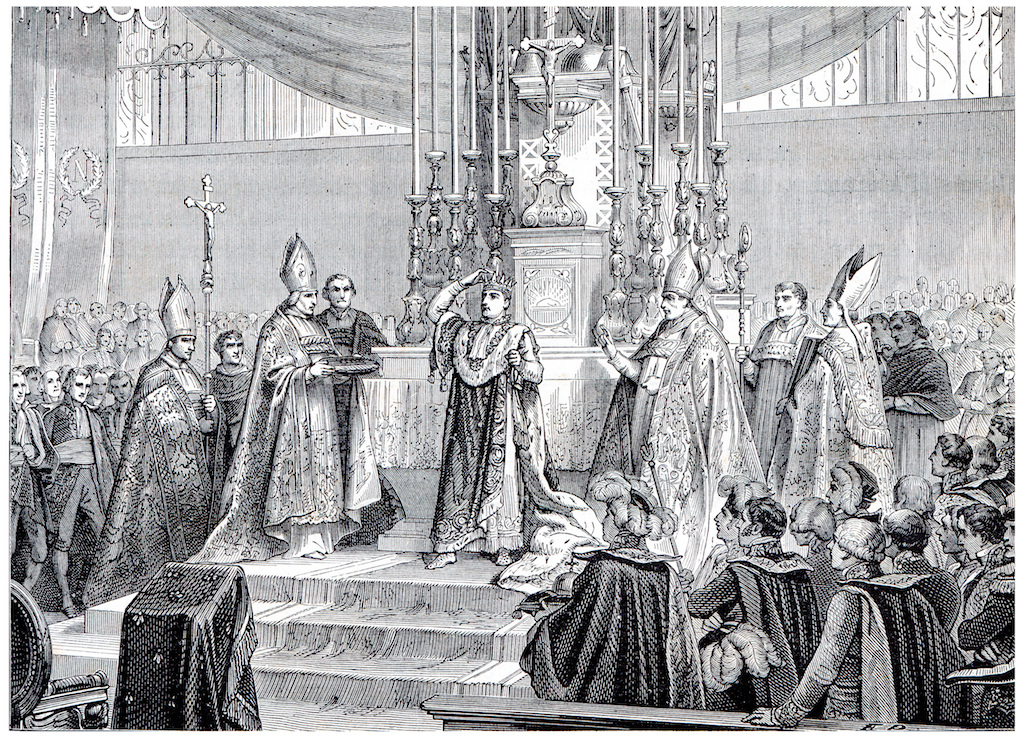

Bonaparte's influence as first consul steadily increased, and in 1804, after a referendum, he was voted emperor of France. To keep hold of power, the new emperor made heavy use of censorship to prevent the expression of any opposition. He also made sure that numerous paintings of him were drawn and displayed prominently in public buildings.

Germaine de Stael published a novel that Bonaparte interpreted as critical of him, and so the author was exiled from France in 1803. At around the time of that exile, de Stael wrote of Bonaparte that "there is only one man in France … one sees a fog that is called a nation, but one can't distinguish anything. He alone is front and center."

Bonaparte also reformed the legal code, introducing the Napoleonic Code, which replaced several local law codes with a national code that was used throughout France and part of Bonaparte's larger empire. While the code had provisions that allowed for freedom of religion, it was very restrictive on women's rights, giving a woman's husband vast power over her.

Under Bonaparte's rule, France was usually at war with other countries. While he was able to inflict heavy defeats on Austria and Prussia, the vast naval power of Britain made it impossible for him to invade Britain. He tried to impose a "continental system," preventing countries in Europe from trading with Britain, but it had little effect.

As time went on, Bonaparte's enemies used new tactics to defeat his army. In 1804, his military suffered a major defeat as French troops in Haiti, who were trying to reimpose slavery, were defeated by a native population fiercely opposed to being enslaved. They used guerilla tactics to destroy the French army. After the defeat, Bonaparte sold Louisiana to the United States and focused his military campaigns on the European continent.

How Bonaparte lost his grasp on Europe

But guerrilla-style tactics soon came to hound Bonaparte in Europe as well. After his army occupied Spain in 1808, the Spaniards resisted by ambushing French troops and then disappearing into the civilian population. Despite the destruction of Spanish villages, the Spanish forces never surrendered, and Bonaparte was forced to keep hundreds of thousands of troops in Spain. Bonaparte called the ongoing insurgency in Spain "the Spanish ulcer." Similar guerrilla tactics were used in southern Italy by people who opposed Bonaparte.

But Bonaparte's worst defeat came when he tried to invade Russia, in 1812. With more than 400,000 soldiers, Bonaparte succeeded in taking Moscow, but the victory was short-lived. Much of the city was destroyed, and with supplies running short Bonaparte was forced to retreat, losing many men during the retreat to the harsh winter, malnourishment, disease and Russian attacks.

By 1813, Bonaparte was on the defensive, with troops from Russia, Great Britain, Spain, Austria and Prussia gradually pushing his troops back toward France. In 1814, forces from those countries invaded France, reaching Paris in April, and forced Bonaparte to abdicate, sending him into exile on the island of Elba in the Mediterranean.

Bonaparte came back to France in 1815 and regained power, but he ruled for only about 100 days before he was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo. This time, he was exiled to St. Helena, an island in the South Atlantic far from France. Watched closely by British guards, Bonaparte lived the last six years of his life on the remote island, dying of gastric cancer in 1821.

Additional resources:

- Learn about the digital reconstruction of the face of a soldier who died during Bonaparte's Russia campaign.

- Read about the reburial of Bonaparte's soldiers in Belarus.

- Learn about a shipwreck that hindered Bonaparte's campaign in the Middle East.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.