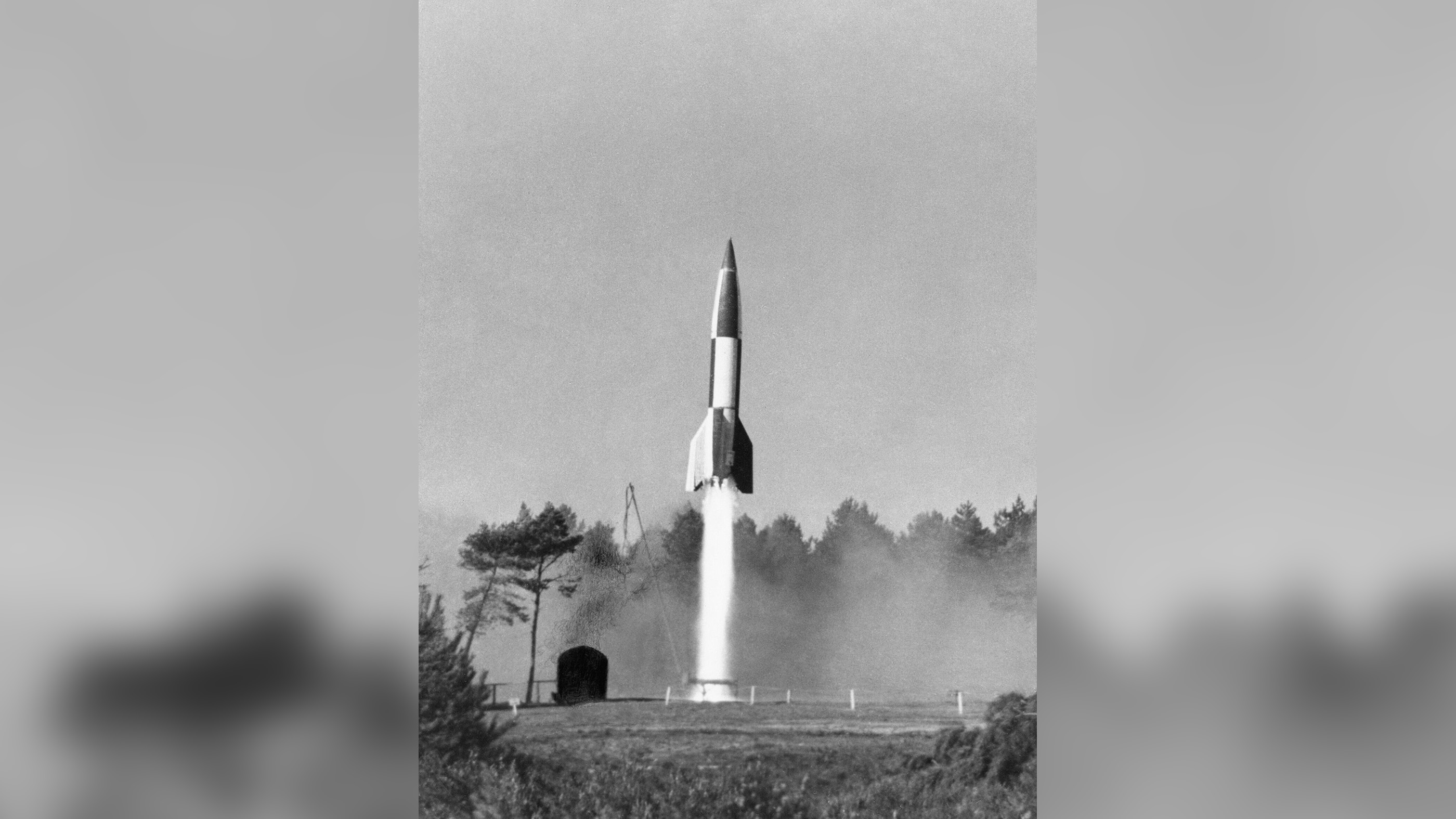

Remains of Nazi V2, the first supersonic rocket, unearthed in South East England

No one could hear these "revenge weapons" coming.

The remains of a V2 rocket fired by Nazi Germany at London during World War II have been unearthed in a field in South East England, where it crashed and exploded before reaching its target.

This is the sixth major excavation of a V2 site carried out by conflict archaeologists and brothers Colin and Sean Welch, who have spent more than 10 years investigating the sites of Nazi "vengeance weapons" launched at the British capital, they said.

They've also excavated the impact sites of dozens of V1 flying bombs, a precursor to modern cruise missiles that were launched mostly from catapults in Nazi-occupied France in 1944 and 1945.

Related: Photos: The flying bombs of Nazi Germany

In the latest V2 excavation near Platt, a village near Maidstone, the researchers — called Crater Locators — recovered more than 1,760 pounds (800 kilograms) of metal debris, including large fragments of the rocket's combustion chamber, from when the rocket exploded at around midnight on Feb. 14, 1945.

The site is now open farmland, but it was an orchard when the rocket struck. The impact was far enough from any houses that no one was hurt, but one elderly woman said later that the noise of the blast damaged her hearing, Sean Welch told Live Science.

The team spent four days at the end of September using a mechanical digger and shovels to excavate the bomb crater, which had been filled in with earth although its location was known. They will now spend up to 18 months conserving the objects before writing up an archaeological report for the county's official historical archives.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team used metal detectors to locate the deepest remnants of the blast, which were more than 14 feet (4.3 meters) underground, Colin Welch said.

"[Although] the rocket is traveling at up to three and a half times the speed of sound, the detonation is not supersonic," he said. "The rocket gets at least 5 feet [1.5 m] into the ground before it starts to detonate properly."

Revenge weapons

The V1 flying bombs and V2 rockets were among the last-ditch "Wunderwaffen," or "wonder weapons," that the Nazi leadership hoped would turn the tide of the war, which Germany was then losing — but they came too late.

According to the Smithsonian Institute's Air and Space Museum, Adolf Hitler ordered the V1s and V2s deployed against London following the devastating Allied bombings of German cities in 1943 and 1944, and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels dubbed them "Vergeltungswaffe," or "revenge weapons." The first V1 hit London on June 13, 1944, and the first V2 hit on Sep. 7, 1944.

Related: Hitler's rise: How a homeless artist became a murderous tyrant

V1s flew at about the speed of a fighter plane at the time, and Royal Air Force pilots soon learned to shoot them down or knock them off course. Their pulse-jet engines also made a lot of noise — they were dubbed "buzz bombs" — so people could hear them coming and try to take shelter.

The V2 rockets, however, were the first supersonic weapons and were greatly feared because no one could hear them coming, and they flew too high and fast to intercept. The German military launched the rockets from sites in Germany to an altitude of roughly 50 miles (80 kilometers); they then fell to their targets, reaching speeds of up to 3,500 mph (5,600 km/h.)

Although V2s were more sophisticated, V1s were much cheaper to make and tended to explode at ground level, rather than after entering the ground, which made them more effective weapons, Colin Welch said.

The V2 rocket attacks on London killed an estimated 9,000 civilians and military personnel, while both of Germany's Vergeltungswaffen combined killed up to 30,000 people, according to the Imperial War Museum in London.

Night launches

Several V2 rockets fell short of the British capital and landed in Kent; Colin and Sean Welch think this was because they were launched at night when the targeting was less accurate. As the V2 campaign progressed, they argue, the launches could be spotted by Allied radar operators, who would then guide fighter squadrons to the location. To avoid the Allied aircraft attacks, the Germans started launching V2s at night when most fighters couldn't fly, which led to worse accuracy by the ground crews who aimed the rockets, they said.

Some of the twisted metal remnants of the V2 that crashed and exploded near Platt in 1944 are embossed with a three-letter code that signifies the factory in Nazi-occupied Europe where the part was made.

Until recently, historians thought all the later V2s were built under the direction of the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun in underground tunnels near Nordhausen, at the foot of Germany's Harz mountains.

But it now seems that the Nordhausen plant was only an assembly line, and the three-letter codes show that the Nazis made the V2 parts in factories as far afield as occupied Czechoslovakia, Sean Welch said.

Von Braun himself is a controversial character. He claimed not to know about Nazi atrocities but he was a member of the Nazi paramilitary SS ("Schutzstaffel," meaning "protection squad") and according to the White Sands Missile Range Museum more than 12,000 forced laborers died on his V2 production line in a single year.

But von Braun was captured by the Americans after the war and became a pioneer of the Space Race; in 1960, he was appointed director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, where he developed the rockets that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the moon.

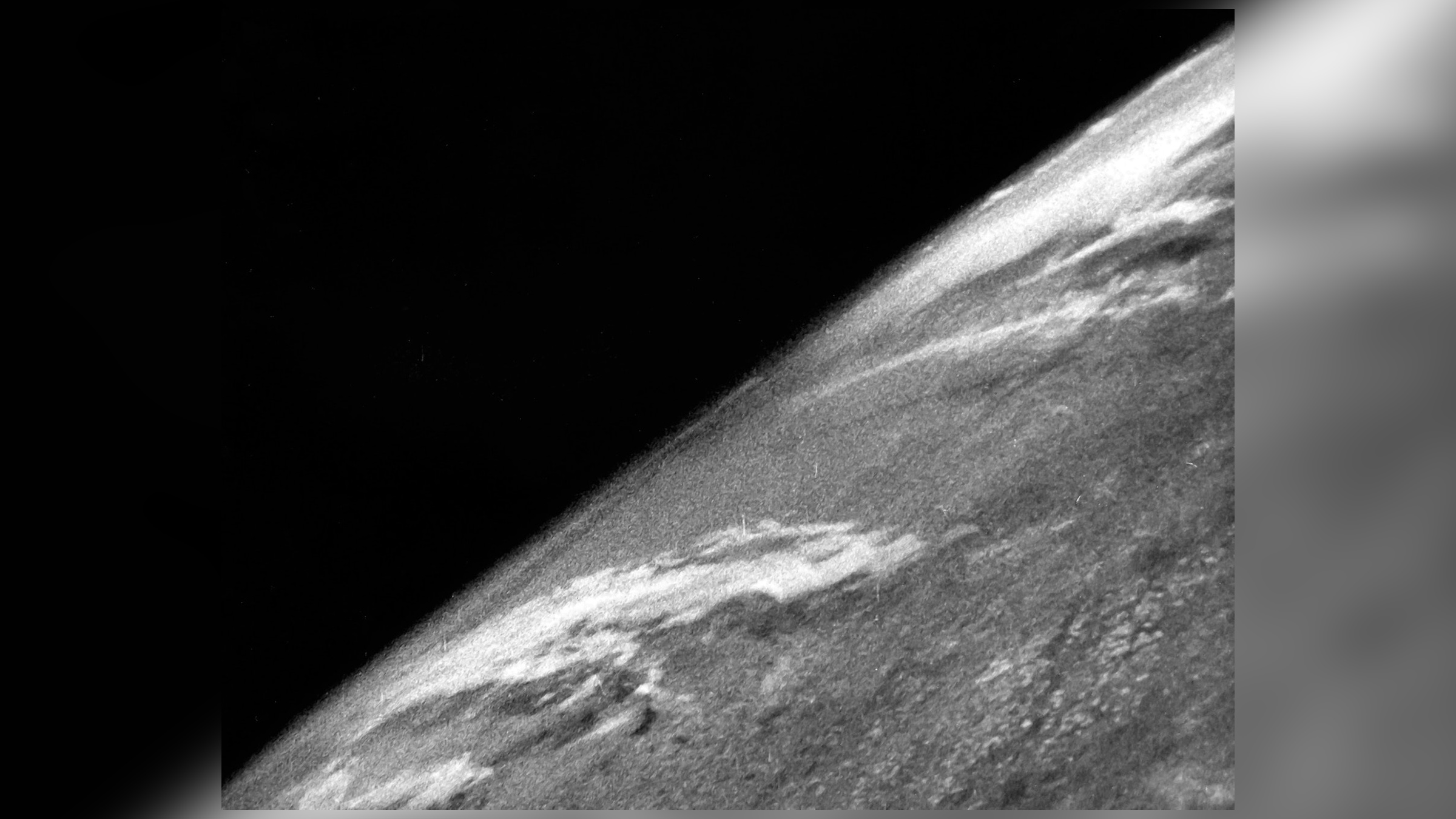

The American military in post-war Germany also captured several V2s at various stages of assembly and shipped them to the United States, where they became the foundation of the fledgling space program. In 1946, a modified V2 launched from White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico reached an altitude of 65 miles (105 km) and took the first photograph of Earth from space, Air & Space Magazine reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.