Gold 'lotus flower' pendant from Queen Nefertiti's time discovered in Cyprus

The jewelry had been buried alongside 155 entombed people.

A precious-gem-studded "lotus flower" pendant similar to one worn by ancient Egypt's Queen Nefertiti has been unearthed in a set of tombs in Cyprus. The pendant is one of hundreds of opulent grave goods from around the Mediterranean region that have been uncovered at the site, including gemstones, ceramics and jewelry.

Archaeologists from the New Swedish Cyprus Expedition first unearthed the two Bronze Age tombs, both underground chambers, in the ancient city of Hala Sultan Tekke in 2018. One hundred and fifty five human remains and 500 funerary goods were found in the tombs, placed in layers on top of one another, suggesting that the burial chambers were used over several generations.

"The finds indicate that these are family tombs for the ruling elite in the city," excavation leader Peter Fischer, professor emeritus of historical studies at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, said in a statement. "For example, we found the skeleton of a 5-year-old with a gold necklace, gold earrings and a gold tiara. This was probably a child of a powerful and wealthy family."

Related: In photos: The life and death of King Tut

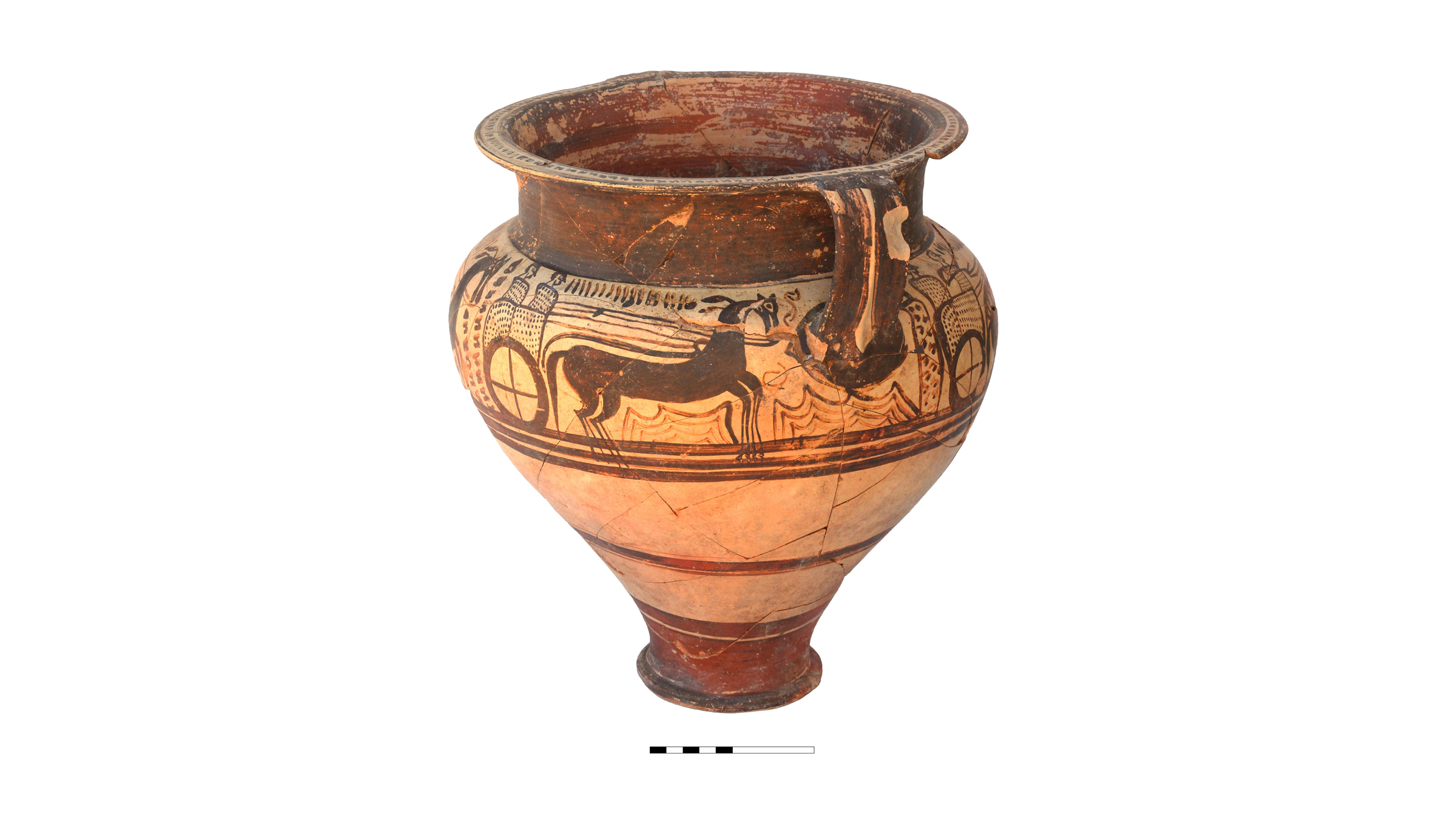

The grave goods include jewelry and other keepsakes made of gold, silver, bronze and ivory, as well as vessels from various cultures. "We also found a ceramic bull," Fischer said. "The body of this hollow bull has two openings: one on the back to fill it with a liquid, likely wine, and one at the nose to drink from. Apparently, they had feasts in the chamber to honour their dead."

Meanwhile, other grave goods included a red carnelian gemstone from India, a blue lapis lazuli gemstone from Afghanistan and amber from around the Baltic Sea — valuables indicating that Bronze Age people in Cyprus took part in a vast trading network. Archaeologists also found evidence of trade with ancient Egypt, including gold jewelry, scarabs (beetle-shaped amulets sporting hieroglyphs) and the remains of fish imported from the Nile Valley, according to the statement.

The archaeological team dated the gold jewelry by comparing it with similar finds from Egypt. "The comparisons show that most of the objects are from the time of Nefertiti and her husband Echnaton [also spelled Akhenaten, the father of King Tutankhamun]", around 1350 B.C., Fischer said. "Like a gold pendant we found: a lotus flower with inlaid gemstones. Nefertiti wore similar jewellery."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The excavation team also uncovered a cylinder-shaped seal crafted from hematite, a mineral with a metallic hue. The seal bears a cuneiform inscription from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that archaeologists deciphered.

"The text consists of three lines and mentions three names. One is Amurru, a god worshiped in Mesopotamia. The other two are historical kings, father and son, who we recently succeeded in tracking down in other texts on clay tablets from the same period, i.e., the 18th century B.C.," Fischer said. "We are currently trying to determine why the seal ended up in Cyprus, more than 1,000 kilometres [620 miles] from where it was made."

An analysis of the ceramic wares in the tombs showed that the styles in which they were crafted changed over time, which also helped date the findings, Fischer said.

Next, the archaeologists plan to analyze the DNA of the skeletons interred in the tombs. "This will reveal how the different individuals are related with each other and if there are immigrants from other cultures, which isn't unlikely considering the vast trade networks," Fischer said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.