Fossilized Brains Found in Ancient Bug-Like Creatures

New evidence of preserved brain tissue from the Cambrian period counters arguments that nervous tissue cannot be fossilized.

Inky stains found in fossils of 500-million-year-old bug-like creatures may be beautifully preserved, symmetrical brain tissue. The fossil find may help lay a heated scientific controversy to rest — the question of whether brains can be fossilized.

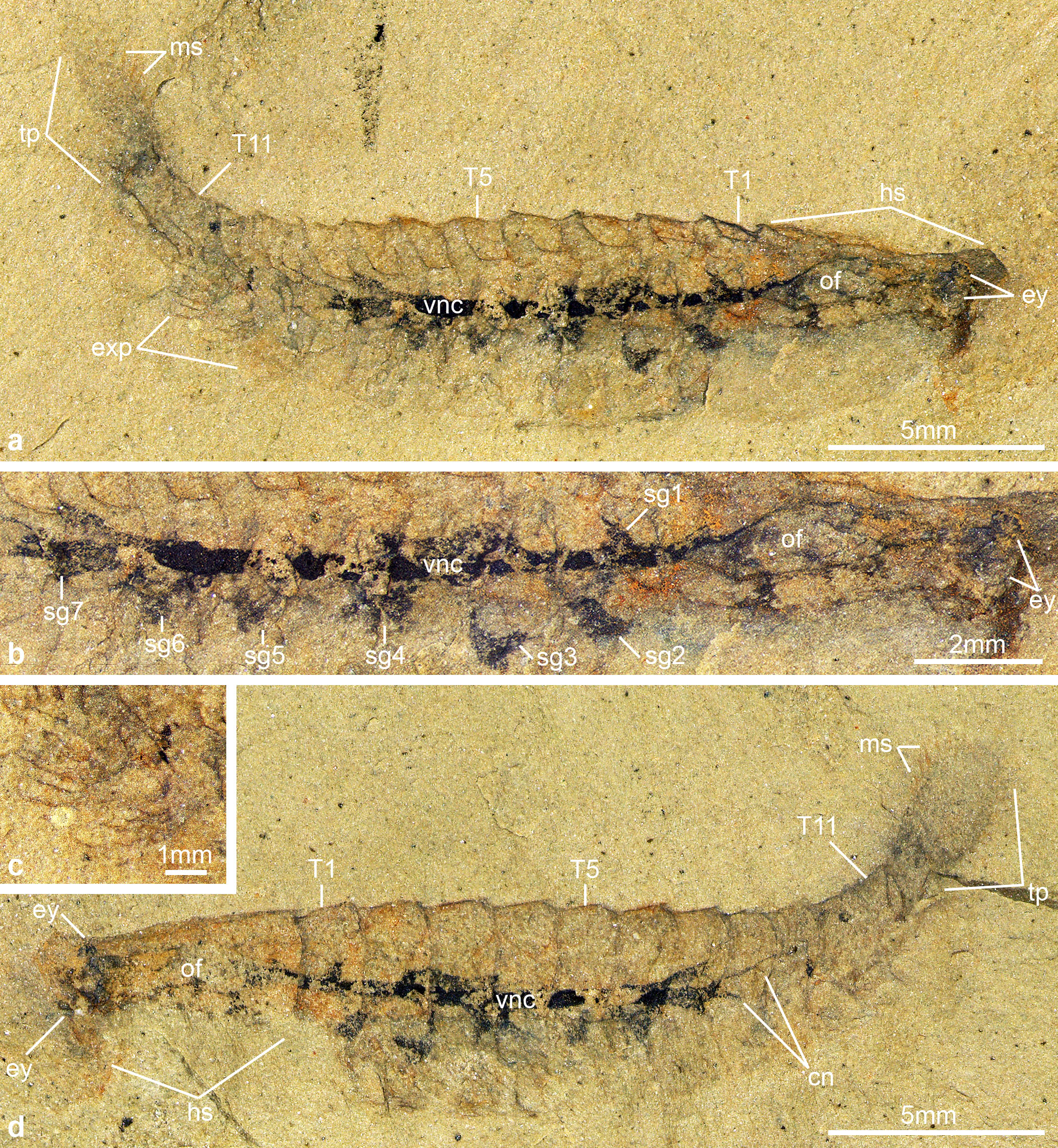

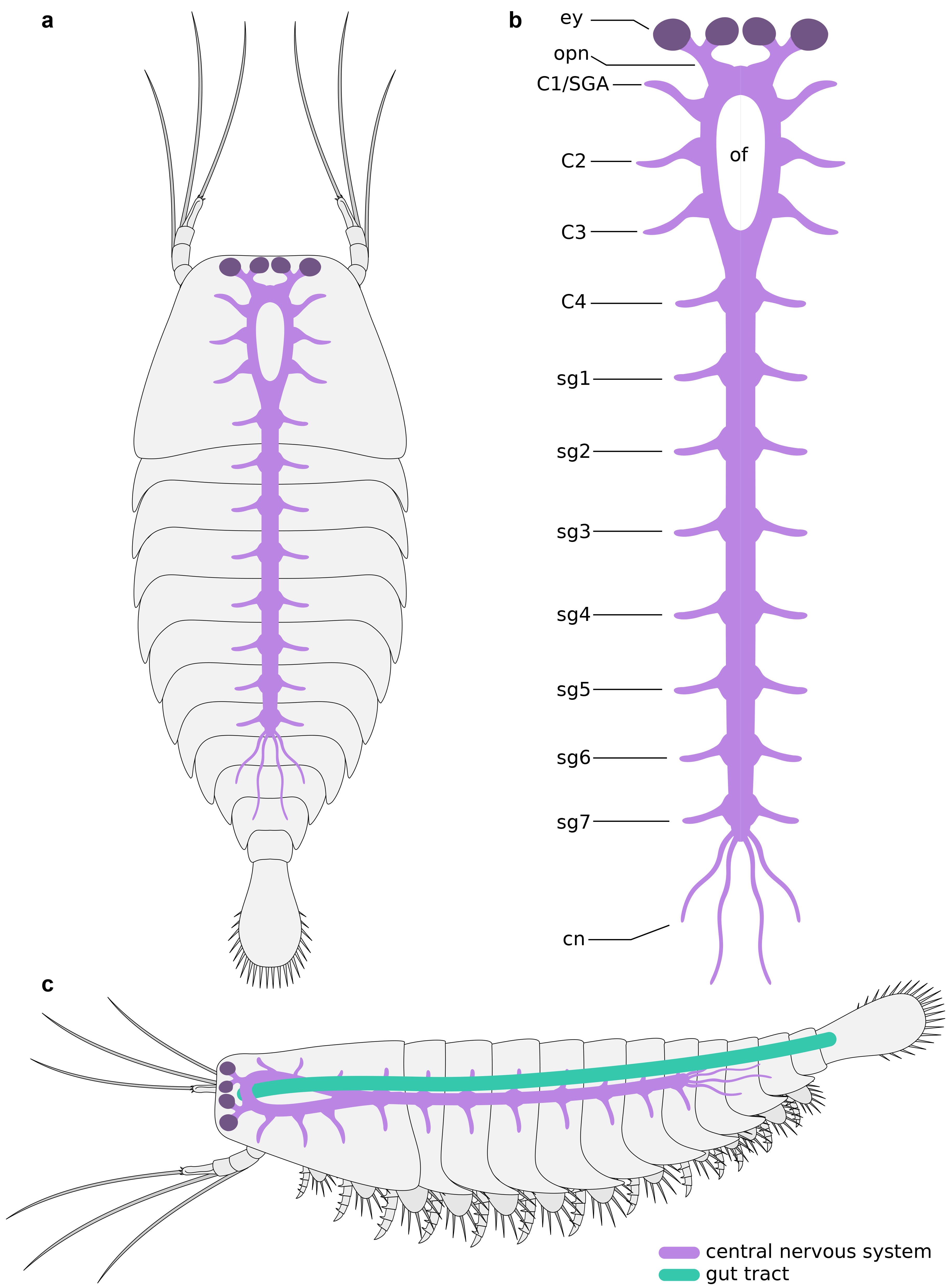

Scientists discovered these splotchy marks in fossils of the arthropod Alalcomenaeus, an animal which shares its phylum with modern insects, spiders and crustaceans. The animals lived during the Cambrian period, which took place between about 543 million and 490 million years ago, and sported a tough exoskeleton that fossilized well. But the soft tissues of the creature's brain and nerves often decayed and therefore disappeared from the fossil record.

Now, a new study, published Dec. 11 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, describes not one but two Alalcomenaeus fossils complete with brains and all their trimmings.

"What we are dealing with in the fossil record are exceptional circumstances. This is not common — this is super, super rare," said co-author Javier Ortega-Hernández, an invertebrate paleobiologist at Harvard University and curator of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Previously, paleontologists have identified only one other Alalcomenaeus specimen thought to have nervous tissue, but the finding was met with skepticism. With two more specimens in hand, scientists can now be confident that nervous tissue can in fact be fossilized and found in exceptional Cambrian arthropod fossils, Ortega-Hernández said.

Related: In Photos: These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

Long-standing debate

Besides Ortega-Hernández and his team, only a handful of researchers have reported finding fossilized nervous tissue in Cambrian-period arthropods. In a 2012 paper, scientists described the first evidence of a fossilized arthropod brain, in a tiny creature called Fuxianhuia protensa. Although widely covered in the media, the report attracted critics.

"They said, 'Rubbish, lot of nonsense,'" said Nicholas Strausfeld, a regents professor in the department of neuroscience at the University of Arizona and co-author of the 2012 study, as well as several others on brain-like features in arthropods. Some paleontologists argued that, based on our understanding of how animals decay, the stained specimens Strausfeld and others unearthed couldn't possibly contain nervous tissue, Strausfeld said. Some theorized that the brain stains must be either a strange fluke of fossilization or fossilized beds of bacteria, known as biofilms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But now, the new study by Ortega-Hernández and his colleagues serves as "a really pleasing validation of earlier work," Strausfeld told Live Science. "He's put to rest a lot of objections from people."

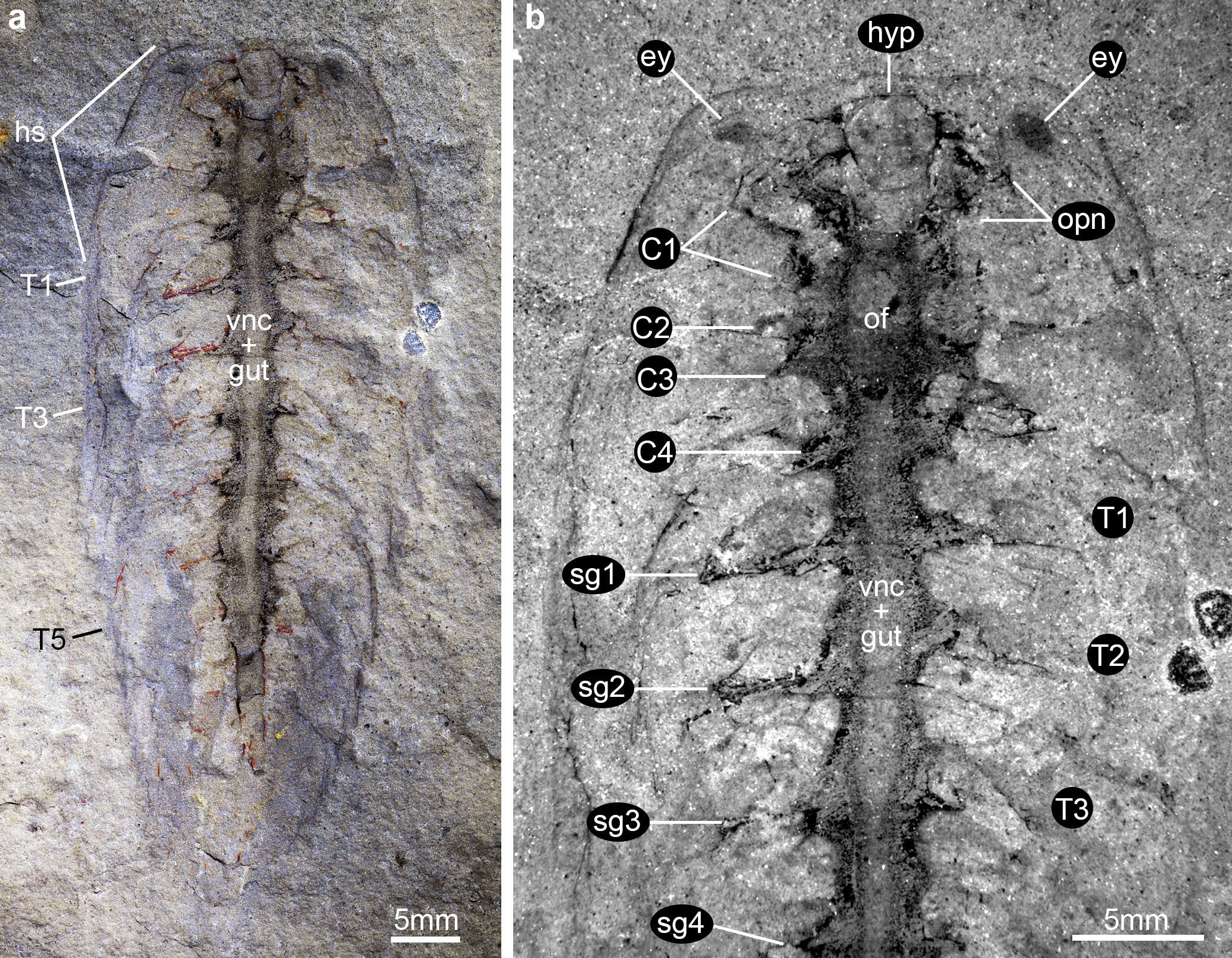

In their study, Ortega-Hernández and his co-authors uncovered a new Alalcomenaeus fossil buried in Utah within a region of geological depressions known as the American Great Basin. The authors noted symmetrical stains along the creature's midline that resembled nervous system structures found in some modern arthropods, including horseshoe crabs, spiders and scorpions. "The nervous system and the gut kind of cross each other, which is really funky but common in arthropods nowadays," Ortega-Hernández told Live Science.

Related: Weird and Wonderful: 9 Bizarre Spiders

The stains also contained detectable levels of carbon, a key element in nervous tissue. The dark splotches also plugged into the animal's four eyes, as would be expected for nervous system tissue. Having checked all these criteria, Ortega-Hernández said that he could confidently report finding fossilized nervous tissue in the newfound specimen.

But to double-check their findings, the authors also examined a second Alalcomenaeus fossil from the American Great Basin. Originally dug up in the 1990s, the specimen sported similar stains and carbon traces to the newfound fossil. What's more, both Great Basin fossils matched descriptions of another specimen that Strausfeld found in China. All three fossils had been found buried in similar deposits, indicating that a unique preservation process allowed all their brain matter to fossilize, Ortega-Hernández said.

Counterarguments

Although Ortega-Hernández and his colleagues checked and double-checked their work, the authors "generally have to be cautious about claiming to have found a genuine fossil brain," Jianni Liu, a professor at the Early Life Institute in the Department of Geology at Northwest University in Xi'an, China, told Live Science in an email. Liu argues that the blobby stains seen in Cambrian fossils might be a "slightly random effect of the decay process" rather than remnants of brain matter.

In a 2018 study, Liu and her colleagues examined about 800 fossilized specimens and found that nearly 10% contained inky stains in the head region. The authors reviewed previous studies of animal decay and found that nervous tissue tends to decay quickly, but gut bacteria can stick around and "produce these so-called biofilms as radiating [stains] which look a bit like parts of a nervous system," Liu wrote.

Related: 5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health

Several paleontologists, including Strausfeld, pointed out that Liu failed to examine fossils that reportedly contained brain tissue, and that lack of primary evidence marks a "major shortcoming" in her study. What's more, the specimens Liu did examine contained asymmetric stains rather than symmetric ones, meaning they would not have been interpreted as brain tissue anyway, Strausfeld said.

Additionally, studies of decay often measure tissue breakdown in water, whereas buried fossils interact with a multitude of chemicals carried in the sediment around them, Ortega-Hernández said. For instance, some studies suggest that a combination of clay and water jump-starts a "chemical tanning" process that toughens soft tissues in the body, similar to how particular chemicals can transform supple cow hide into leather, Ortega-Hernández said.

More work must be done to clarify the role of sediment in fossil preservation, but as of now, ample evidence suggests that arthropod remains placed under intense pressure solidify over time, Strausfeld said. The brain and nerves within the animal flatten out in the process, and because nervous tissue contains lots of fat, the structures repel water and "have some resistance against decay," he said.

Despite the evidence in their favor, Ortega-Hernández, Strausfeld and their colleagues may need to dig up a lot more arthropod brain bits to convince naysayers that ancient brains can fossilize.

"We appreciate the authors' efforts to justify their results as being genuine nervous tissue, but remain sceptical while the data comes from only two fossils," Liu said. "New data is always welcome, but as we noted previously, we would be more convinced if the anatomical features appeared in a consistent form across several specimens independently."

- In Photos: Oldest Homo Sapiens Fossils Ever Found

- 10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know about Animals

- Ancient Footprints to Tiny 'Vampires': 8 Rare and Unusual Fossils

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.