Poop stains visible from space reveal hidden colonies of Antarctic penguins

But all of these new colonies are located in areas likely to be highly vulnerable to climate change.

Penguins might be good at hiding from humans, but they can't hide their poop from the giant satellites circling our planet.

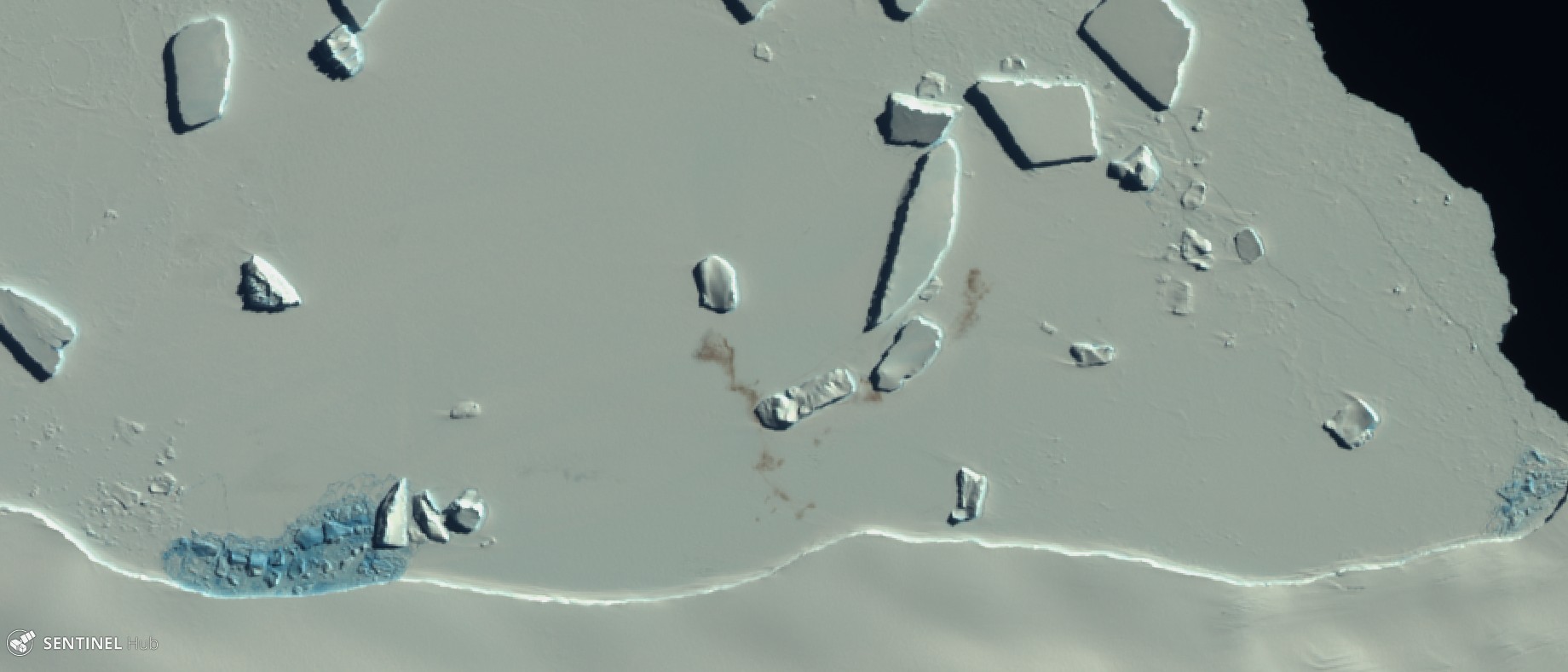

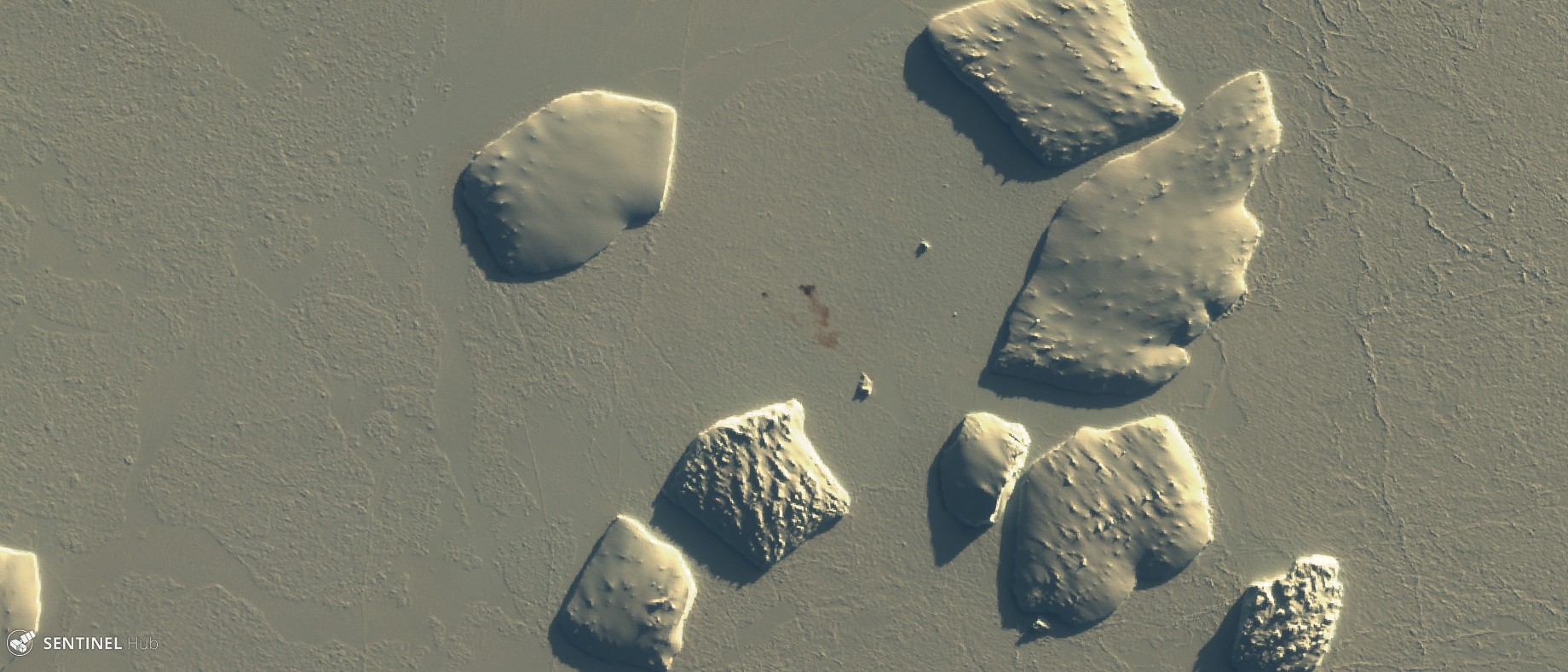

New imagery revealed penguin poop stains on the white blankets of the coldest continent. And those dark spots suggest that there are nearly 20% more emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica than previously thought.

This is both "good and bad news," as all of these new colonies are located in areas likely to be highly vulnerable to climate change, according to the study, published on Aug. 4 in the journal Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.

It's not easy to count just how many emperor penguins live on Antarctica as the animals typically breed in very frigid, remote and difficult to reach places. To get around this, for the past decade, scientists with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have been searching for penguins indirectly by looking for poop stains in satellite imagery.

Related: In photos: The emperor penguin's beautiful and extreme breeding season

In the new study, scientists analyzed images taken in 2016, 2018 and 2019 by the European Space Agency's Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites. They reviewed the images for brown pixels, which represent guano stains.

The images revealed eight new emperor penguin colonies — and confirmed the existence of three others previously identified — bringing the continent's total to 61 colonies. But most of the colonies were so small, the researchers had to use multiple images to confirm they existed, according to the study. Those 11 new colonies increase the known emperor penguin population by 5% to 10%, or up to 55,000 additional birds, bringing the total population of the world's tallest living penguin to somewhere between 531,000 and 557,000, the study found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Whilst it's good news that we've found these new colonies, the breeding sites are all in locations where recent model projections suggest emperors will decline," Phil Trathan, the head of conservation biology at BAS said in a statement. "Birds in these sites are therefore probably the 'canaries in the coal mine' — we need to watch these sites carefully as climate change will affect this region."

Almost all emperor penguin colonies depend on stable sea ice anchored to the land for breeding, according to the study. And this land-anchored ice needs to remain stable for around 9 months from when they breed to when their chicks fledge.

Previous projections have suggested that climate change and melting ice is likely going to spark a decline in emperor penguin populations, according to the statement. Even if global temperature increases only by 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) — which climate scientists think is the best-case scenario — Antarctica's population of emperor penguins will decrease by at least 31% over the next three generations, one 2019 study in the journal Global Change Biology found.

Some of these colonies were located far offshore, some up to 112 miles (180 kilometers) off the coast, on sea ice formed around icebergs that had grounded in shallow water, according to the BAS. This was the first time emperor penguins were found to breed so far from shore and that means there are potential breeding habitats in places we don't know of, the authors wrote. However, "these areas away from the coast are more northerly, they will be in warmer areas and therefore will be more likely to be susceptible to early sea ice loss," the researchers wrote in the study.

This isn't the only time scientists have found penguins from their poop. Two years ago, another group uncovered a previously unknown supercolony of 1.5 million Adélie penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula's Danger Islands, by finding poop stains in satellite images, according to a previous Live Science report. These Adélie penguins had somehow thrived despite climate change, while their counterparts on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula had already had population declines.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.