Newfound millipede breaks world record for the most legs

It's a millipede, literally.

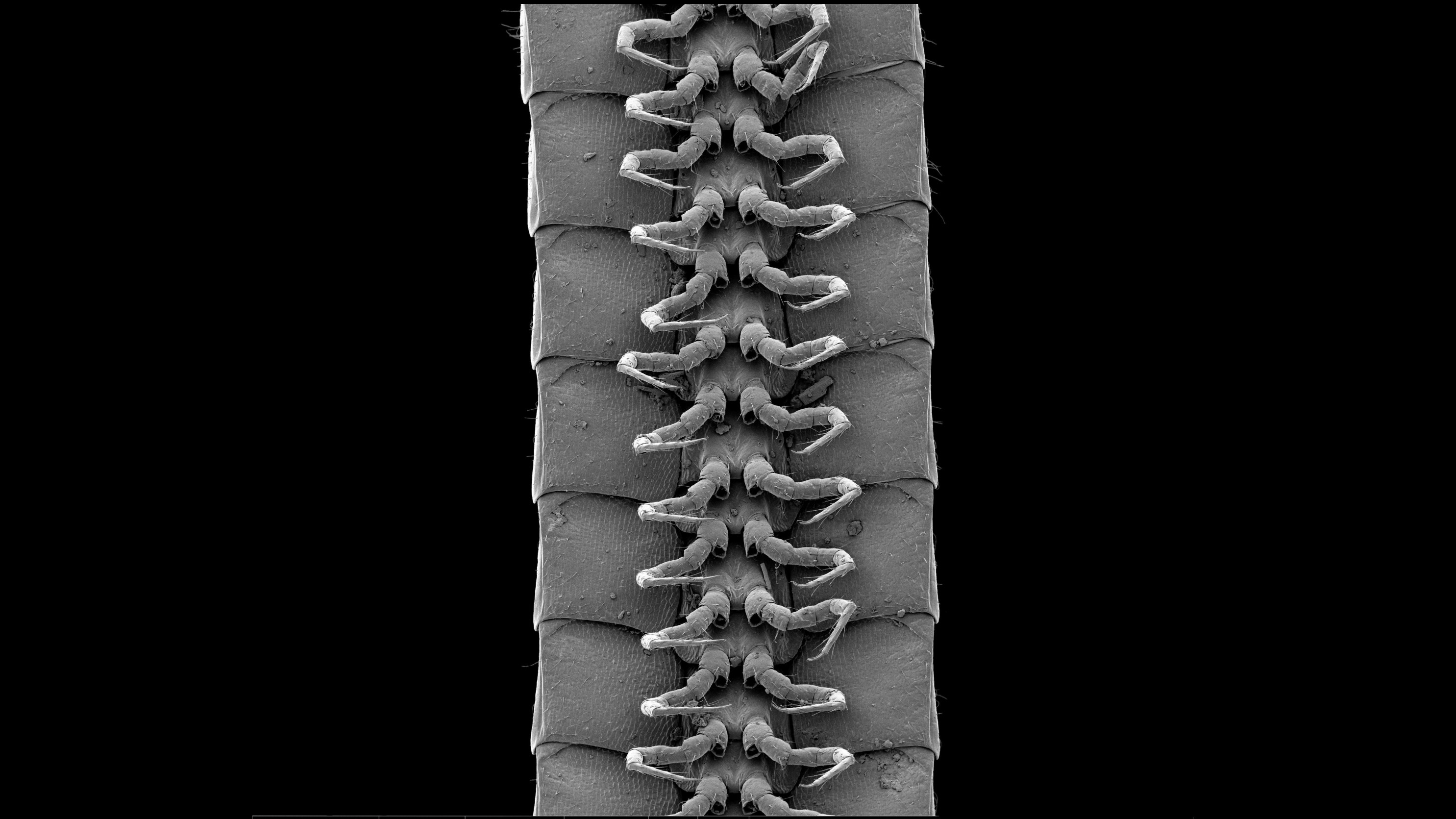

A newfound species of millipede has more legs than any other creature on the planet — a mind-boggling 1,300 of them. The leggy critters live deep below Earth's surface and are the only known millipedes to live up to their name.

"The word 'millipede' has always been a bit of a misnomer," said Paul Marek, an entomologist at Virginia Tech university and lead author of the study describing the newfound species. All other known millipedes Millipedes sport far fewer legs than their name implies, with many species having fewer than 100 legs. Until now, the record-holder was a species called Illacme plenipes, a deep-soil dweller known to have as many as 750 legs.

Related: Extreme life on Earth: 8 bizarre creatures

But the newfound species, Eumilipes persephone — named after Persephone, the daughter of Zeus who was taken by Hades to the underworld — is the leggiest known animal on the planet. One specimen Marek analyzed has 1,306 legs, which smashes the current record.

The new world record-holder is a pale, eyeless creature with a long, threadlike body that’s nearly 100 times longer than it is wide. Its cone-shaped head has enormous antennae for navigating a dark world governed by pheromones, and a beak that’s optimized for feeding on fungi. The legs are difficult to count because the animal tends to coil like a little watch spring, Marek said.

The copious collection of legs also provides a hint about these creatures' lifespan.

"I suspect these animals are extremely long-lived," Marek told Live Science. Millipedes grow steadily, adding body segments, called rings, throughout their lives. Entomologists can count these segments like tree rings to establish relative ages between individuals of the same species.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In all, Marek analyzed four specimens — two males and two females — all of which were different lengths and thus different ages. The shortest of the bunch had 198 rings and 778 legs. The longest had 330 rings and 1,306 legs. Given how often other species of millipedes add body segments, this suggests E. persephone typically lives to be between 5 and 10 years old, as compared with the 2-year lifespan typical of other millipedes.

Don't expect to see one of these rummaging in your backyard leaf litter, though. This species was discovered 200 feet (60 meters) below Earth's surface in a relatively unexplored environment built from banded iron formations and volcanic rock.

The creatures were first spotted in a region of Western Australia known as the Goldfields, which is a nexus for mineral extraction. Companies prospecting for nickel and cobalt bore deep, narrow holes between 65 and 328 feet (20 and 100 m) deep, Marek said. If the miners don’t find any of these metals, the holes are capped and abandoned.

"Some time ago, entomologists from Western Australia came up with the idea to sample these boreholes," because they provide the perfect opportunity to peer into subterranean ecosystems. By lowering cups of leaf litter and other detritus to certain depths, waiting for a few weeks, and then retrieving them, researchers can sample the wide variety of life thriving far below our feet. The leggiest species on the planet is but one such discovery.

The new find shows "there are a lot more discoveries to be made," Marek said. And though species that live so deep beneath our feet can seem removed from life on the surface, these ecosystems play an important ecological role that’s tied to surface life, Marek said. Subterranean decomposers help recycle nutrients that surface life relies on, and the deep soil layers these animals live in filter toxins from our drinking water. Yet we still know so little about the world beneath our feet.

"There's so much more biodiversity out there," he said, "We just don't have the full picture yet."

Originally published on Live Science.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.