'Gummy squirrel' found in deep-sea abyss looks like a stretchy half-peeled banana

Of the 55 specimens collected, 39 may be new species.

If there were such a thing as an underwater freak show, then this would be it. Scientists from the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London have discovered a mysterious menagerie of marine megafauna deep in the Pacific Ocean, and dozens of the oddball creatures could be species that are unknown to science.

With the assistance of a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) during the summer of 2018, scientists recovered 55 specimens lurking on the western edge of an abyss located between Hawaii and Mexico, roughly 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) below the sea surface. Of that assemblage of oceanic oddities, seven were recently confirmed to be newfound species; the researchers' findings were published July 18 in the journal ZooKeys.

While the eastern side of the abyss has been explored quite regularly, its western portion, which is known as the Pacific Clarion-Clipperton Zone and includes several nearby seamounts (underwater mountains), is less accessible and has therefore remained largely unexplored, making it a prime locale for discovering new species.

"About 150 years ago, the [HMS] Challenger expedition explored this area, but as far as I know, there hasn’t been much study done since that time," Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras, a NHM biologist in the life sciences department and the study’s lead author, told Live Science. "This part of the ocean has barely been touched."

Related: What’s the weirdest sea creature ever discovered?

During the 2018 expedition, the scientists more than made up for lost time. One after another, each new creature they discovered was as fascinating as the one that came before: from an elastic, banana-shaped sea cucumber known as a gummy squirrel (Psychropotes longicauda) — the individual that they found stretched nearly 2 feet (60 cm) long — to a sea sponge in the genus Hyalonema, whose body resembled a tulip.

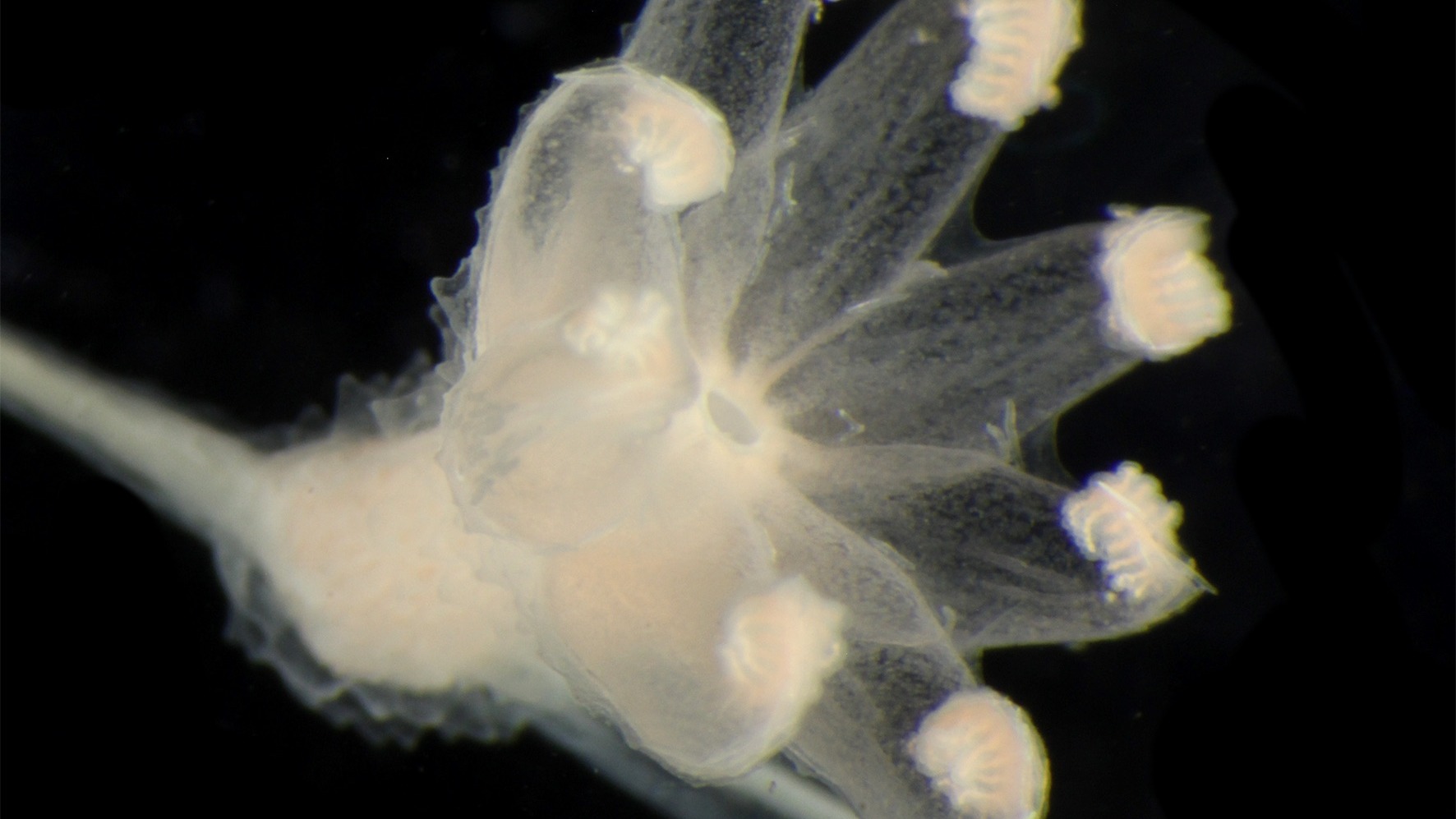

Of the potential new species that the scientists discovered, the one that caught Bribiesca-Contreras' attention was a type of coral in the Chrysogorgia genus. Its pale orange polyp resembled that of C. abludo, a species that's usually found in the Atlantic Ocean. But the researchers later identified it as a new species that has yet to be named. This marks the first time that a coral of this genus has been found in the Pacific.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"At first we thought it was the same species, but upon further molecular work, we learned that it’s morphologically different," Bribiesca-Contrerasshe said. "One thing that always strikes me is that a lot of these lifeforms we see haven’t changed much over the course of millions of years, which is crazy to think [about]," she said. "Many of these species we’ve seen as fossils, and they look exactly the same now."

Many of the bizarre adaptations in these deep-sea weirdos have persisted for so long because they improve the animals' chances of surviving in a very punishing environment, Bribiesca-Contrerasshe added.

"Where they live this deep in the ocean can be challenging," she said. "There’s no light, their bodies are withstanding crushing pressure and there's little nutrition available."

Prior to the NHM expedition, many of these animals have only been glimpsed in photographs or videos, or are known from their fossilized remains. This mission enabled scientists to study the specimens as they moved freely through their ocean habitat, and then later in the lab. Such investigations allow scientists to better understand remote and untouched deep-sea ecosystems — an important goal as the deep-sea mining industry continues to expand worldwide.

"We really need to understand this ecosystem so that we can come up with plans for conservation," she said. "At this point, the little information we have about this environment and the species that live there makes it very difficult to know how damaging mining could be."

Originally published on Live Science.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.