Nobel Prize in physics awarded to 3 scientists for their black hole discoveries

Trio includes only the fourth woman ever to receive the physics Nobel.

The Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to three scientists for their work involving some of the cosmos's most mysterious, darkest, secrets — black holes.

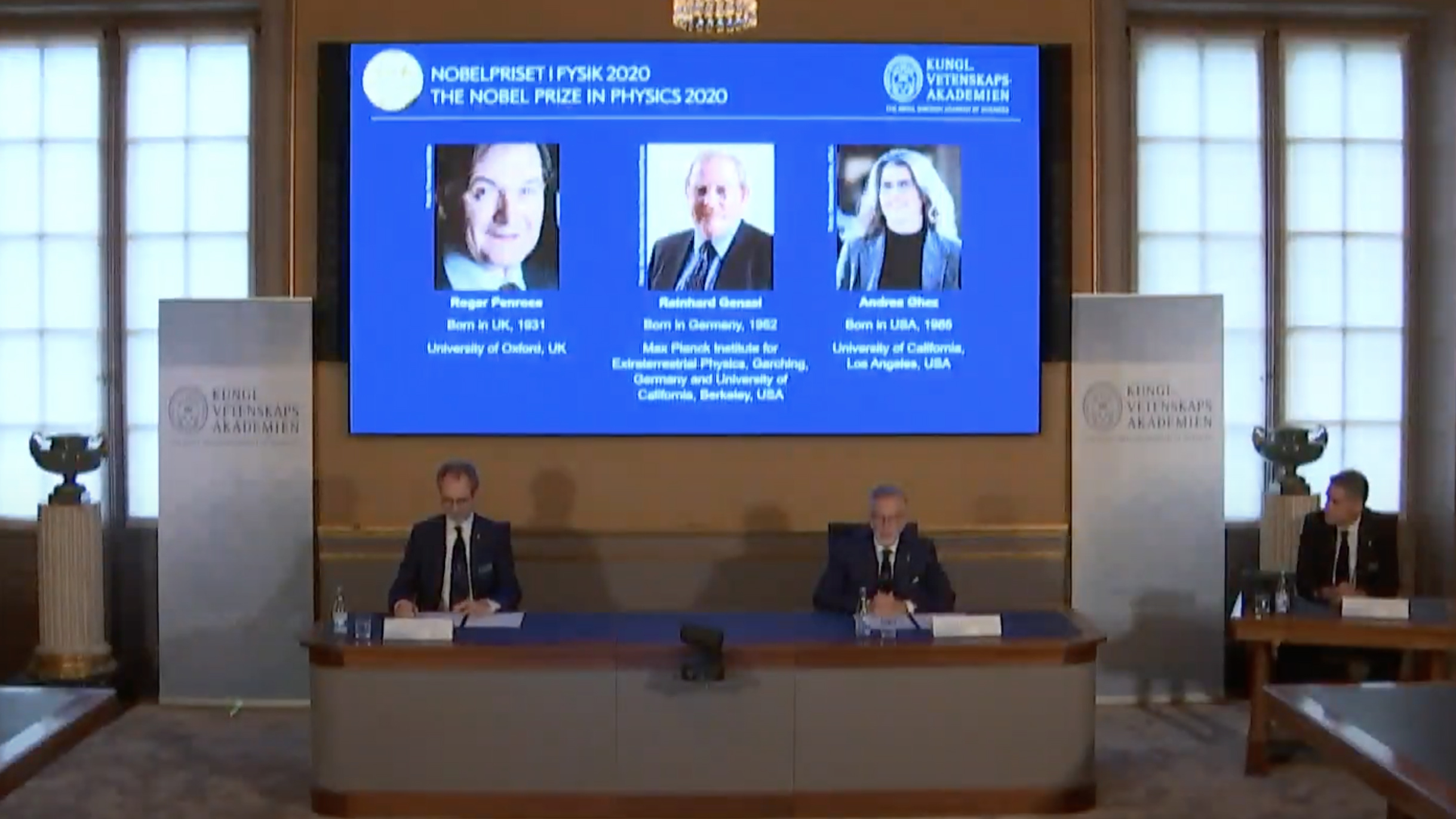

Roger Penrose, of the University of Oxford in the U.K., received one-half of the prize "for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity," while Andrea Ghez of University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Reinhard Genzel, of the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany, jointly shared the other half "for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the center of our galaxy," the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced this morning (Oct. 6).

Ghez is only the fourth woman to be awarded a Nobel in physics ever. (The other three were Marie Curie in 1903, Maria Goeppert-Mayer in 1963 and Donna Strickland in 2018.)

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

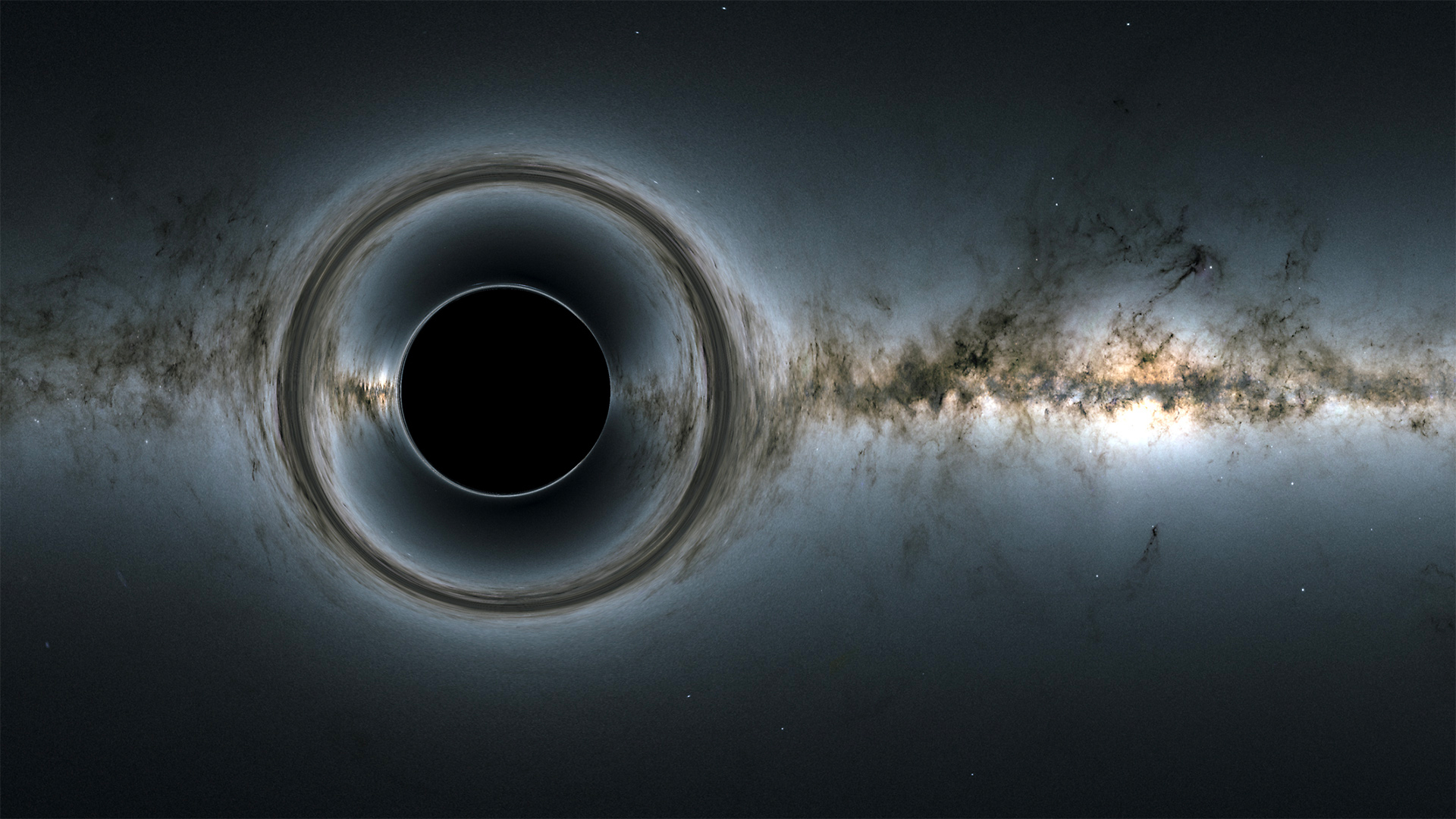

For his part, Penrose showed with eloquent mathematical models that the very existence of black holes is a direct consequence of Albert Einstein's most famous theory; in fact, Einstein didn't believe such heavyweights — objects that devour everything, even light, that comes within their reach — even existed.

Even so, his theory of general relativity predicts that gravity results from the warping of space-time. Under this theory, massive objects (like black holes) put cosmic dents in this space-time fabric so that other nearby objects can't help but fall into these gravity divots. One of the predictions to come out of general relativity is that black holes have an event horizon, a demarcation beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape.

In January 1965, just 10 years after Einstein had died on April 18, 1955, Penrose revealed that black holes can, and do, form, describing them in detail in an article that is regarded even today "as the most important contribution to the general theory of relativity since Einstein," the academy said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Penrose found that at the heart of black holes lies an infinitely dense core called a singularity, where the laws of nature break down.

Related: 8 ways you can see Einstein's theory of relativity in real life

For their part, teams led by Ghez and Genzel revealed the dark secret at the center of the Milky Way.

Since the early 1990s, by focusing on a region at the heart of our galaxy called Sagittarius A*, Ghez and Genzel independently found that some super-heavy object there is pulling on clusters of stars and causing them to whiz around at mind-bending speeds, the academy said. In fact, their teams discovered that an object weighing in at a whopping 4 million solar masses is packed into a spot no larger than our solar system.

Not only did the two predict the existence of this black behemoth, but they developed telescope methods that allowed them to see through dense clouds of interstellar gas and dust at the center of the Milky Way. They refined these techniques to compensate for distortions that occur due to Earth's atmosphere. And in the end, the two groups provided the strongest evidence so far that a supermassive black hole lurks at our galaxy's heart.

Related: 11 fascinating facts about our Milky Way galaxy

"The discoveries of this year's Laureates have broken new ground in the study of compact and supermassive objects," David Haviland, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said in the academy's statement. "But these exotic objects still pose many questions that beg for answers and motivate future research. Not only questions about their inner structure, but also questions about how to test our theory of gravity under the extreme conditions in the immediate vicinity of a black hole."

Last year's physics Nobel prize was awarded to three scientists for unraveling the structure and history of the universe and for changing humanity's perspective of our planet's place in it, Live Science previously reported.

Penrose will receive half of the 10 million kronor (about $1.2 million) Nobel prize, while Ghez and Genzel will split the other half.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.