Northern Lights: What are the aurorae borealis?

Here's what causes the gorgeous northern lights and where you can see the glowing sky show.

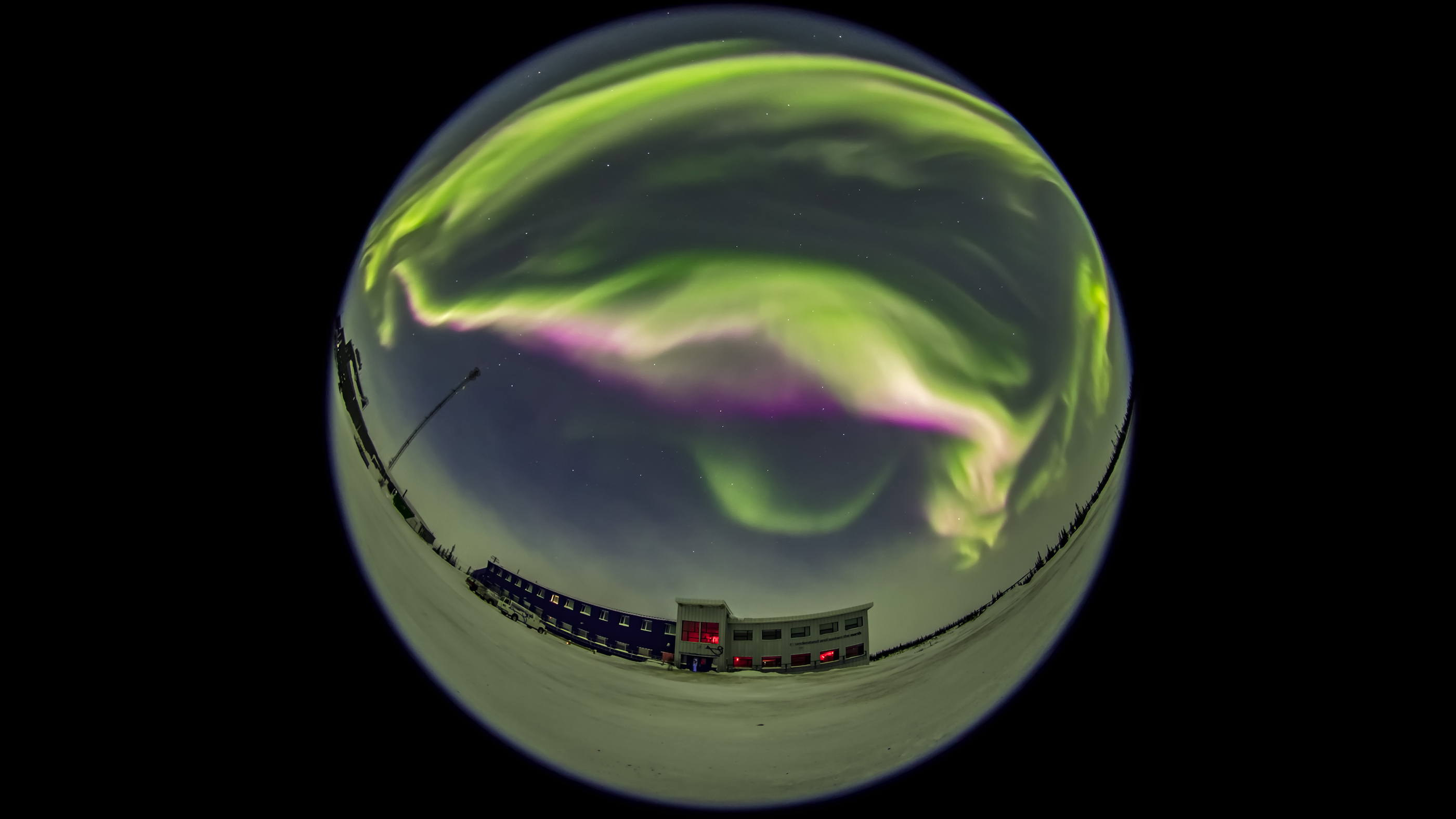

The northern lights are a phenomenon that appear in the sky when charged particles coming from the sun slam into oxygen and nitrogen molecules in the atmosphere, ionizing those molecules and causing them to glow. These lights can only typically be seen at high northern latitudes, and they can vary from a weak glow on the horizon to billowing green and red sheets covering the sky.

Where can you see the northern lights?

As the name suggests, the northern lights are best seen as far north as possible, in any region circling the Arctic, including northern Canada, Iceland and Greenland, the Scandinavian countries, Russia, and Alaska (and any bits of water in between). Generally, the best spot to see them is between 10- and 20-degrees latitude. They technically happen all the time, but the light of the sun during the day washes them out. NASA provides a helpful tool for forecasting northern light events and where the best spot on the Earth is to see them.

What do the northern lights look like?

The northern lights come in a variety of shapes and colors. The most common form is a general whitish "haze" or static glow just above the horizon. In more spectacular shows, the lights can be seen directly overhead as they form billowing, undulating curtains and sheets of blue, green and red. The red — the rarest of the colors — comes from highly energized particles striking oxygen in the upper atmosphere. The blues and greens come from particles hitting nitrogen in lower levels of the atmosphere, according to NASA.

Why does it need to be cold for northern lights to happen?

Despite popular misconceptions, it doesn't have to be cold out to see the northern lights. But they can only be seen at night, and at the northernmost latitudes where there is little — and sometimes no — daylight during the winter months, so to go hunting for northern lights you're generally going to need to bring some layers.

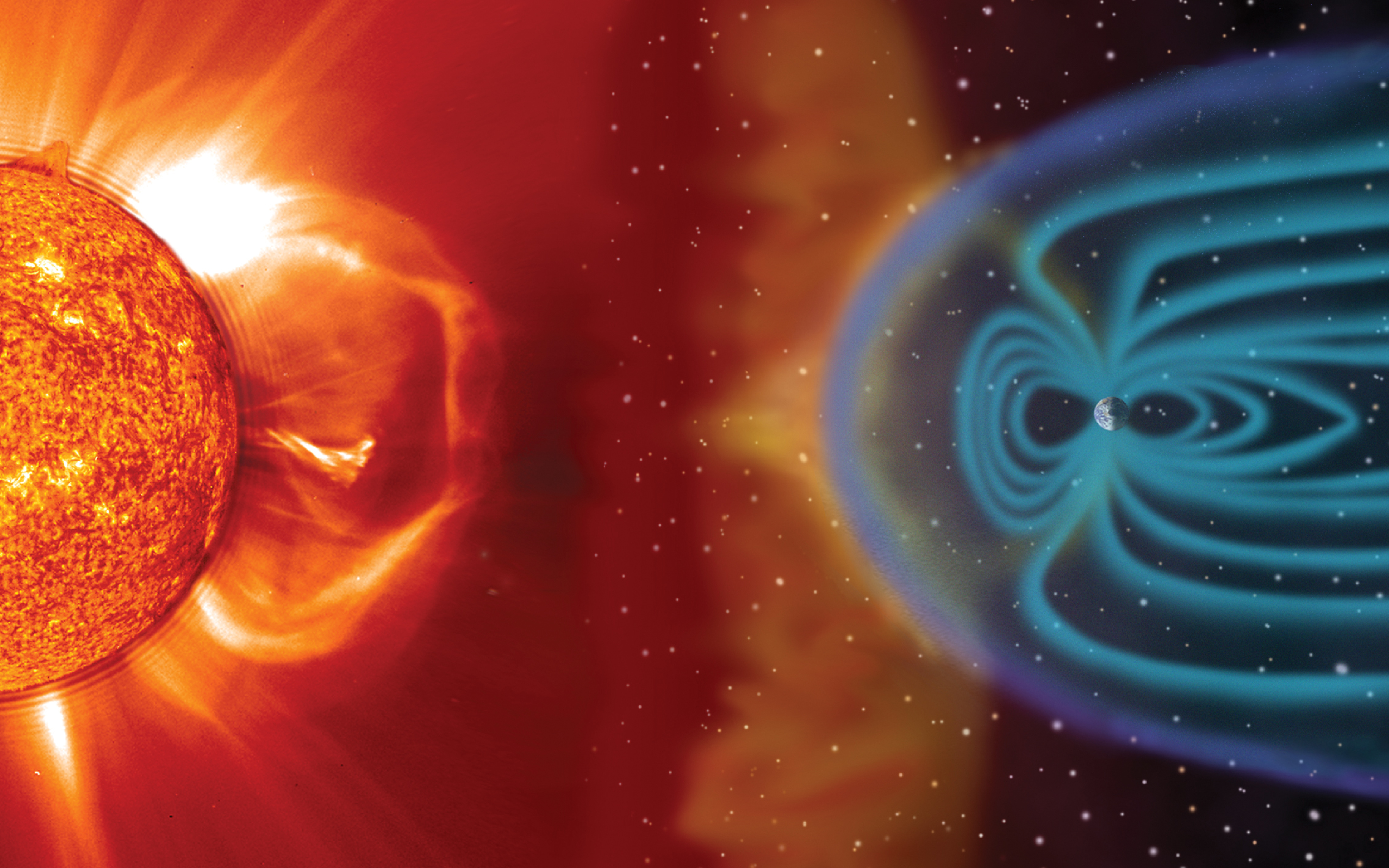

That said, sometimes the northern lights can stretch south. Here's how: The charged particles from the sun are called the "solar wind," and they are constantly streaming through the solar system.

These charged particles get caught up in the Earth's magnetic field, which funnels some of them to the north pole and some to the south poles, where they slam into our atmosphere, creating the remarkable display. So the northern lights are matched by southern lights, but since it's much more difficult to visit the Antarctic, the northern lights are much more commonly viewed.

When the sun is cycling through a more active phase, the solar wind can become much stronger. Also, sometimes the sun releases an enormous number of particles all at once in an event called a coronal mass ejection. During those events, the northern lights will appear much brighter and can be seen farther south, because the excess charged particles overwhelm the usual funnel system of the Earth's magnetic field, according to the Space Weather Archive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Who first identified the northern lights?

People throughout history have seen and recorded northern (and southern) lights, and the lights feature commonly in many folklore traditions. For example, the Emperor Xuanyuan from Chinese mythology, the founder of Chinese culture and the ancestor of all Chinese people, was said to have been fathered by the northern lights. To the Maori people of New Zealand, the southern lights were great torches in the sky lit by their ancestors as they sailed south, according to NASA.

Even the Greeks, who almost never experienced the northern lights themselves, knew about them from travelers and traders, and they were described by the fourth-century explorer Pytheas.

What are the aurorae borealis?

Another name for the northern lights is the aurora borealis, a name given to the effect by Galileo Galilee. The "aurora" references the Roman goddess of the dawn, and "borealis" is the Greek name for the north wind, so a rough translation of the name is "northern dawn."

Galileo thought the northern lights were caused by sunlight reflecting off of high-altitude clouds, and Benjamin Franklin theorized that they were caused by concentrations of electrical charge. In 1741, Swedish astronomer Olof Hiorter observed a compass needle rhythmically swing back and forth in time with the undulations of the lights, confirming that magnetic fields were also involved. However, it wasn't until the early 1900's that Norwegian scientist Kristian Birkeland first outlined the connection between solar charged particles, the elements in the atmosphere, and the northern light shows, according to a British Antarctic Survey site.

Do other planets get northern lights?

Earth isn't the only planet to host northern lights. Jupiter and Saturn have magnetic fields stronger than Earth's, so they have truly impressive displays. Even Uranus and Neptune, far from the sun, host northern lights. Weak northern lights have been detected on Mercury, Mars and even Venus. The last is remarkable because Venus doesn't have a magnetic field, so that planet's northern lights appear as diffuse patches throughout its atmosphere.

Astronomers hope to identify northern lights outside the solar system. The most likely candidates are brown dwarfs, which are bodies larger than planets but smaller than stars. According to Joachim Saur, a geophysicist at the University of Cologne, the northern lights on brown dwarfs are expected to be a trillion times brighter than they are on Earth.

The northern lights on brown dwarfs would be so strong that they should appear in ultraviolet radiation (UV), making them relatively easy to detect. "Brown dwarfs are relatively cold objects," Saur told Live Science. "Therefore, they do not emit thermal UV, which the sun for example does. Therefore, brown dwarfs are ideal objects to search for UV aurora outside the solar system, as there is no competing UV emission expected."

Additional resources

- In his book "Aurora Borealis: The Ultimate Hunting Guide," landscape photographer Leonardo Papèra provides information on when and where to see the northern lights and how to capture great photographs of the phenomenon. From reviewer comments, this book seems best for beginners.

- PBS provides a fun hands-on activity for kids, with a visual step-by-step guide for creating wall art of the northern lights.

- The University of Alaska Fairbanks has an "aurora forecast" resource that includes maps showing real-time activity over North America, Europe, North Pole, South Pole and specifically across Alaska. The site also has information about when and where to see the northern lights in general.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.