The surface of the ocean is now so hot it's broken every record since satellite measurements began

The upper levels of the ocean have never been this hot. Blame the end of La Niña and the ever-present heating effect of climate change.

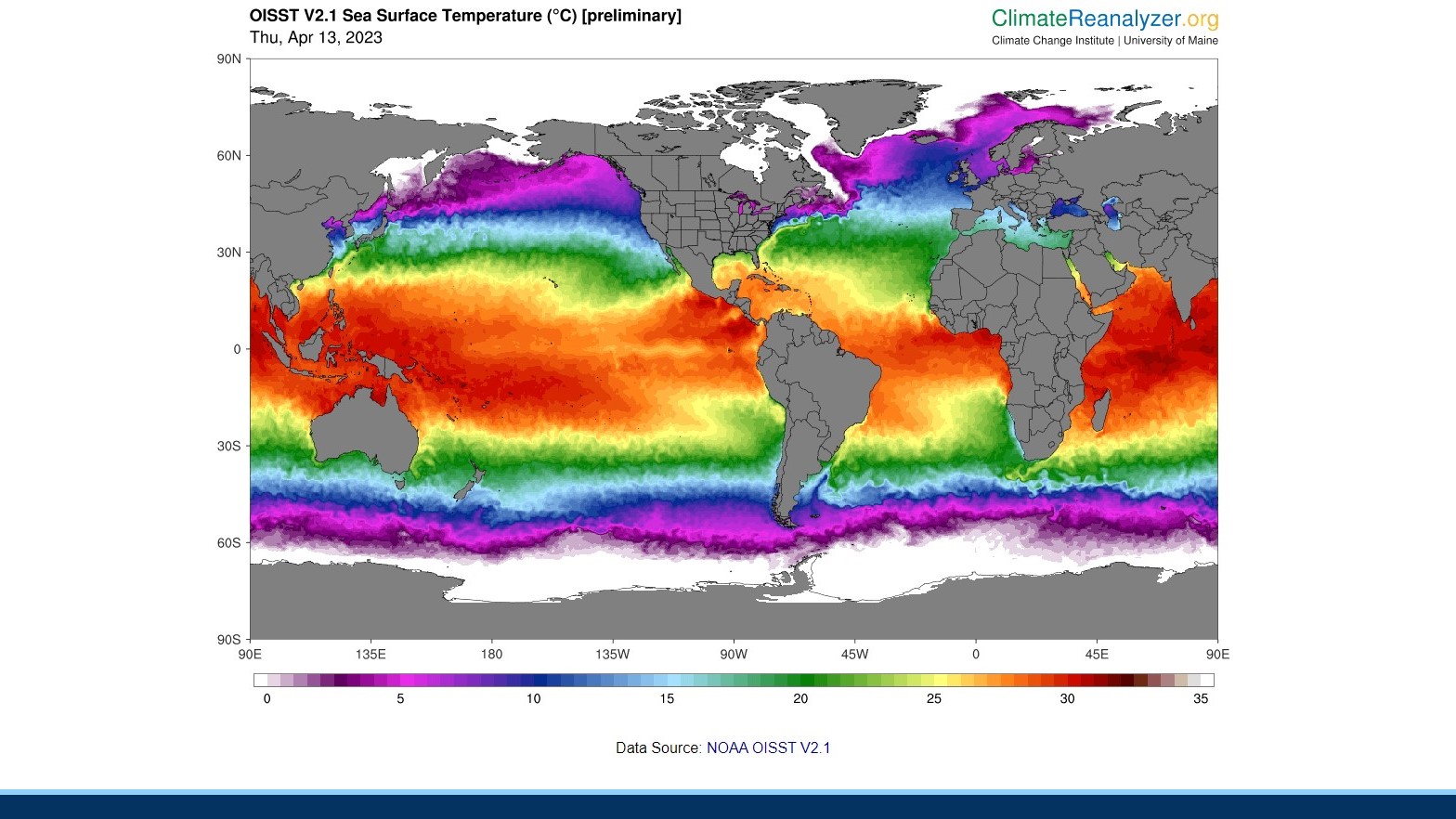

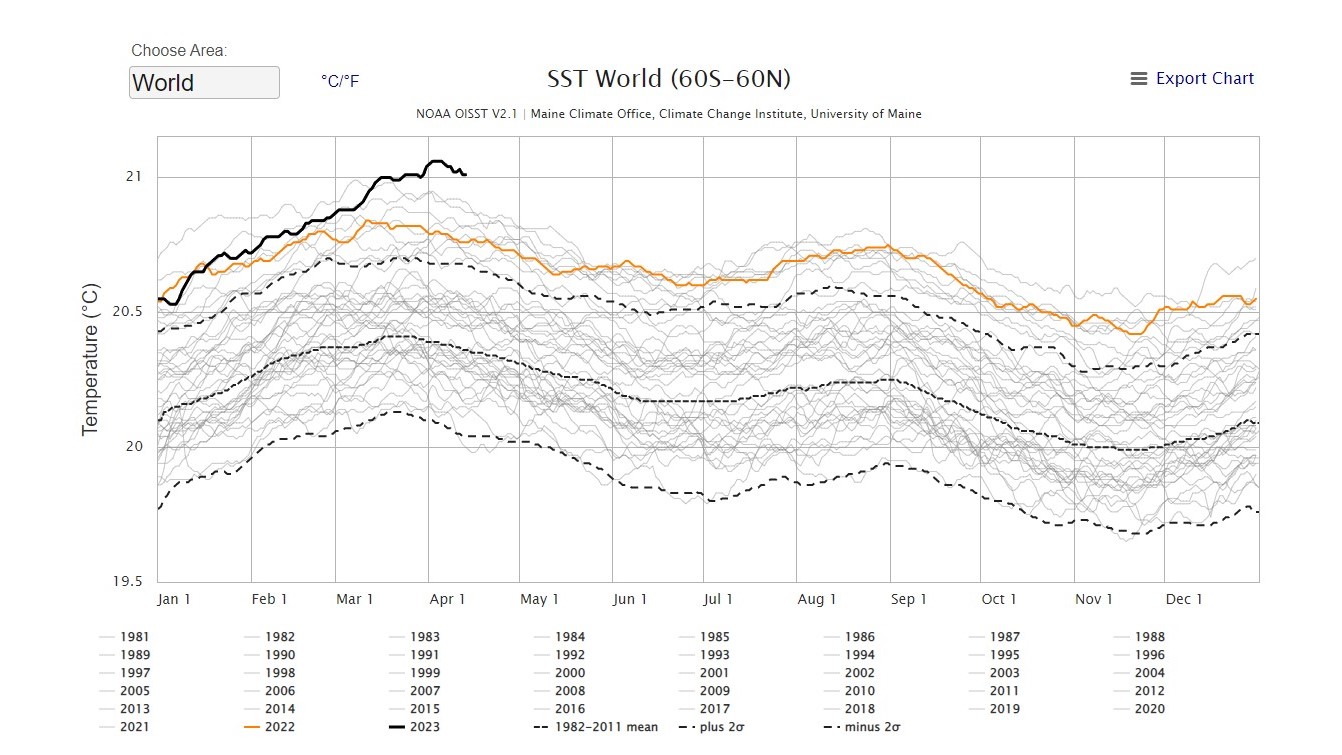

Ocean surface temperatures have hit an all-time high this month, breaking every record since satellite measurements began in the 1980s.

Temperatures reached a global average of 69.98 Fahrenheit (21.1 degrees Celsius) in the first days of April. The previous record of 69.9 F (21 degrees C) was set in March 2016. Both are more than a degree higher than the global average between 1982 and 2011, which runs at around 68.72 F (20.4 C) in early spring, according to data from the University of Maine Climate Reanalyzer.

The new record is the result of the buildup of heat from climate change, now unsuppressed by La Niña — a natural ocean cycle of cold surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific that had been ongoing for three years, but which ended in March.

"Now La Niña is over and the tropical Pacific, which is a huge expansive ocean, is warming up," said Michael McPhaden, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle.

Related: Alarming heat waves hit Arctic and Antarctica at the same time

The background trend across the ocean surface, land surface, and atmosphere, is one of warming, McPhaden said. As greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, all three heat up. But the trends wobble up and down a bit based on La Niña and El Niño cycles. (During El Niño years, the Pacific surface heats up.)

"Even though greenhouse gas concentrations in 2022 were the highest ever, it was not the warmest year on record" in terms of global surface temperatures, McPhaden said. That’s because of La Niña. "Twenty-sixteen was the warmest year on record, and that’s because we had this high burden of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere plus a major El Niño. The combination shot the global surface temps into record territory."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some calculations put 2020 as the hottest year on record, while others call it a tie between 2016 and 2020. NOAA's calculations put 2020's average global land and ocean temperatures at 1.76 F (0.98 C) higher than average and only 0.04 F (0.02 C) cooler than 2016.

Currently, the Pacific is in a neutral state of neither El Niño nor La Niña. But forecast models put the chances of tipping into an El Niño later this year at roughly 60%, McPhaden said, which could mean another record-breaking heat year. There is typically a lag between when these oceanic cycles start and when surface temperatures heat up, he said.

"It’s likely that if we have a big El Niño, we would see a new record set in 2024," he said.

Still, it's difficult to predict El Niños from early spring trends, McPhaden said, because the oceanic system is volatile this time of year and can easily swing from one pattern to another.

Climate scientists are still trying to unravel how ocean warming will alter the typical cycle of La Niña and El Niño, he said, but the current consensus is that extremes in both directions will become larger and more frequent. Major El Niños and their accompanying high sea surface temperatures in the Pacific may become twice as common by the end of the 21st century, McPhaden said, which would mean that instead of occurring approximately every 20 years, they might happen every 10.

The current extremes are already affecting ocean life. Marine heat waves, where ocean temperatures in a particular region rise above the levels that native organisms can tolerate are becoming more common. Particularly vulnerable are corals, which expel the symbiotic single-celled organisms that they host when the water becomes too hot. Corals can survive this process, called bleaching, every once in a while — but if it happens too often, the corals will die.

"This is one of the big concerns about rising ocean temps, how it’s going to affect marine ecosystems," McPhaden said. "Coral reef communities have real economic consequences, from the tourism and livelihood of island nations but also protein from the sea. They're a tremendous food source for many nations, and the threats of global warming and pollution and overfishing is a triple whammy."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.