A Woman Placed an Octopus on Her Face for a Photo. Then It Bit Her.

Octopuses have sharp beaks and can deliver venomous bites.

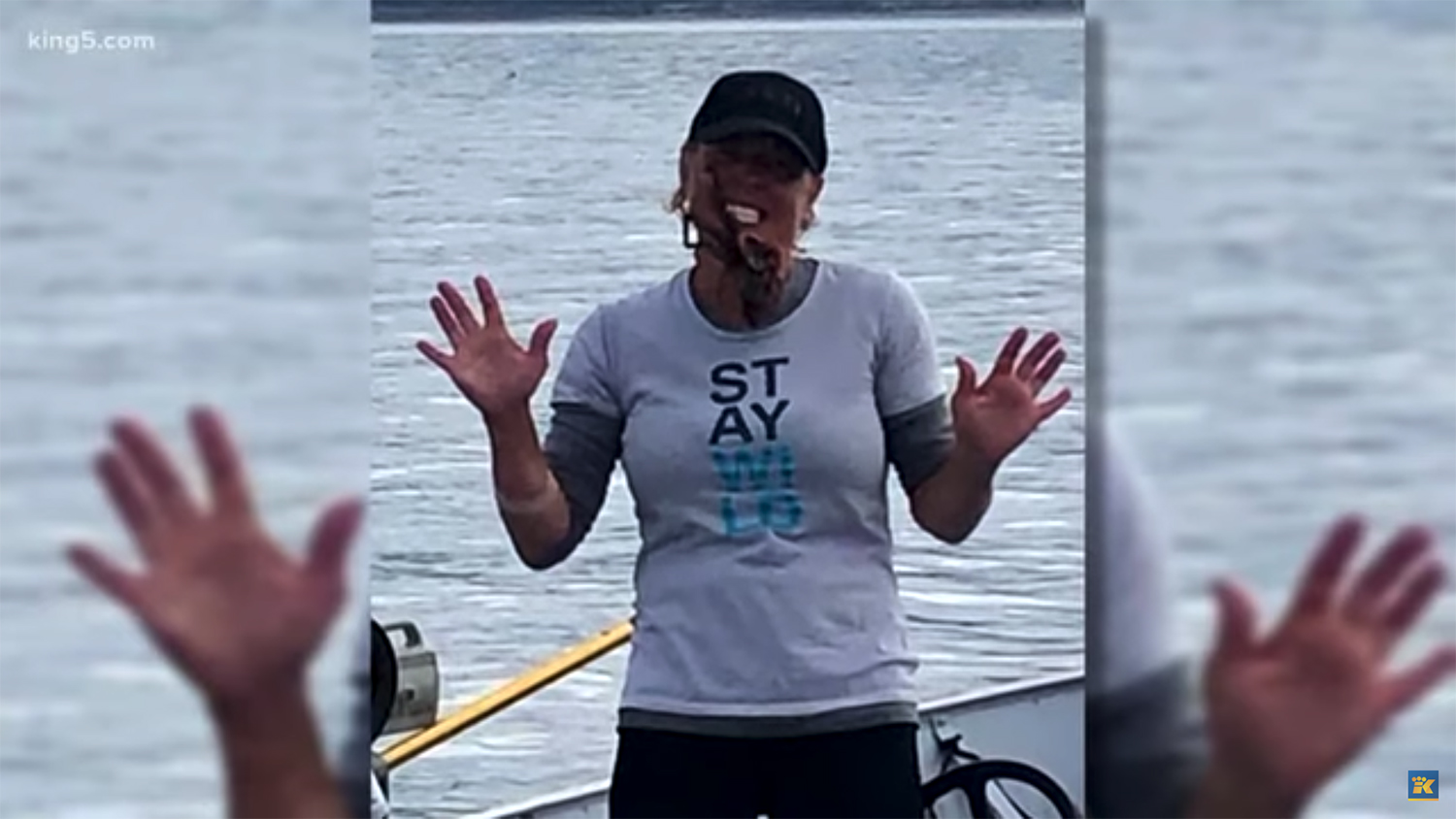

A woman's ill-advised photo attempt with an octopus recently went horribly wrong: After she draped the cephalopod on her face, the octopus dug in with its suckers and bit her on the chin, causing a painful infection that sent her to the emergency room.

Jamie Bisceglia, a resident of Fox Island, Washington, and owner of the fishing company South Sound Salmon Sisters, was trying to create a memorable image for a photo contest, King 5 News reported on Aug. 5.

Bisceglia was at a local fishing derby in Puget Sound on Aug. 2 when she noticed that a fisherman had caught an octopus; she "borrowed" the animal to take a photo for that derby's contest. When she placed the octopus on her face, it sank its beak into her chin — "not once, but twice. It was like a barbed hook going into my skin," Bisceglia told King 5 News.

Related: 8 Crazy Facts About Octopuses

The wound bled for 30 minutes and was intensely painful. After two days elapsed, she was having difficulty swallowing and experienced severe swelling in her face, throat and arms, according to King 5 News. She visited the emergency room at Tacoma General Hospital and received antibiotics. But doctors told her that the swelling may come and go for months to come, Bisceglia told KIRO 7 News.

Bisceglia identified the octopus as a young giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), but it could also be a Pacific red octopus (Octopus rubescens), said Sandy Trautwein, vice president of animal husbandry at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California.

Though octopuses' bodies are soft and boneless, they have hard beaks made of chitin, the same substance that makes up the exoskeletons of arthropods such as insects, spiders and crustaceans, Trautwein told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"An octopus beak looks similar to a parrot's beak and is embedded in strong muscle tissue called a buccal mass," she said. After an octopus has captured a meal with its muscular arms, it uses its beak and drill-like tongue to break through the tough shell of its prey.

"Once there is a hole in the shell, octopuses inject venomous saliva into their prey to paralyze or kill it," Trautwein said.

Paralyzing toxins

In most octopuses, this venom contains neurotoxins that cause paralysis. Saliva in the giant Pacific octopus contains the proteins tyramine and cephalotoxin, which paralyze or kill the prey. Other proteins, such as tryptamine oxidase, dissolve tissue and break it down "into a gel-like form," Trautwein said.

Octopus bites can cause bleeding and swelling in people, but only the venom of the blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata) is known to be deadly to humans.

In addition to octopuses' hunting prowess, there's a lot to admire about these cephalopods: They conduct daring escapes from their tanks, go for walks on beaches and demonstrate impressive camouflaging skills.

But the safest way to appreciate these animals is from a distance. Octopuses are curious creatures and generally not aggressive toward people. But they will defend themselves if provoked and are capable of causing serious injury — as Bisceglia found out the hard way.

"Wild animals are unpredictable and should be respected," Trautwein said.

- Photos: Deep-Sea Expedition Discovers Metropolis of Octopuses

- In Photos: Amazing 'Octomom' Protects Eggs for 4.5 Years

- Photos: Ghostly Dumbo Octopus Dances In the Deep Sea

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.