Octopuses fling shells and sand at each other, and scientists caught their battles on video

Watch debris from the sea bottom fly, as octopuses hurl sand and other projectiles at their neighbors in an Australian bay.

It's no wonder that, with so many arms, octopuses turn out to be great pitchers. They can even target other octopuses with bits of seafloor debris — and score a direct hit.

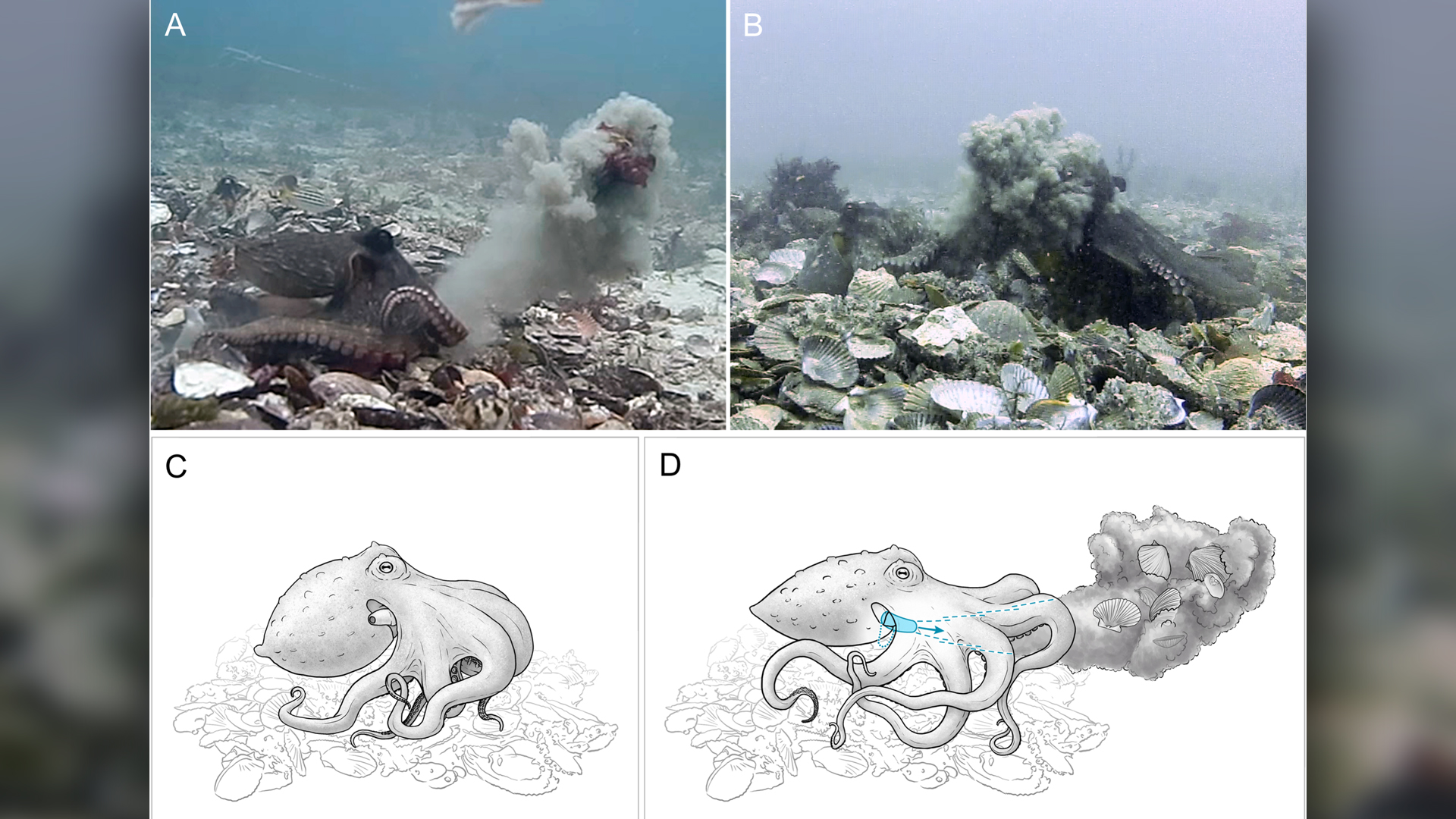

For the first time, researchers have observed the famously brainy cephalopods deliberately hurling clumps of sand, bits of algae and even shells at each other, though they don't actually toss with their arms as people do. Rather, they use their arms to gather projectiles and then propel them using jets of water expelled from a siphon under their arms. Scientists captured video footage of this unusual behavior in gloomy octopuses (Octopus tetricus) in Jervis Bay on the southern coast of New South Wales in Australia and described their findings Nov. 9 in the journal PLOS One.

"In some cases the projected material hits another octopus, or another object (a fish or a camera)," the scientists wrote in the study.

After examining 24 hours of footage recorded on stationary underwater cameras in 2015 and 2016, the study authors identified 102 examples of about 10 octopuses picking things up and throwing them. Often, the objects flew up to several body lengths away from the thrower.

"Doing this underwater, even for a short distance, seems especially unusual and quite hard to do, making this an even more striking behavior," study co-author David Scheel, a professor of marine biology at Alaska Pacific University in Anchorage, told Live Science in an email.

The octopus behavior that scientists captured on video is unusual for animals — just a few types of social mammals are known to throw things at each other, the researchers reported (footage credit: Godfrey-Smith et al., 2022, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0).

Related: Octopuses may be so terrifyingly smart because they share humans' genes for intelligence

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Both male and female octopuses would throw debris, though two females performed about 66% of all the throwing. As for what motivated the octopuses to start hurling debris, around 32% took place while the octopuses were cleaning their dens. But 53% of the silt chucking happened during an interaction with another octopus, a fish or one of the cameras.

Other octopuses got pelted by the lobbed debris in 17 cases. In some incidents, the target would raise an arm right before a missile launched, "perhaps in recognition of the act in preparation," the scientists wrote. "Octopuses in the line of fire ducked, raised arms in the direction of the thrower, or paused, halted or redirected their movements."

But were the throwers intentionally trying to hit their octopus targets?

"The throws during interactions differed from throwing when other octopuses were not present," Scheel said. "Throws that hit an apparent target were a bit different, in ways suggestive of aiming, from throws that did not hit," hinting that debris flinging was targeted.

Humans typically teach toddlers that throwing things is not the best way to communicate. But for other animals that live in close-knit communities — such as chimpanzees, capuchin monkeys and dolphins — chucking objects at members of the same population can serve as an important social cue, according to the study.

Octopuses are known to be extremely dextrous and capable of manipulating diverse objects. For example, the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) stacks and carries coconut shells, which it uses to build a "mobile home." But octopuses, as a rule, are not social creatures; they typically live alone, and when they encounter other octopuses, they sometimes fight them or even eat them.

However, in recent decades, a growing body of evidence suggests that octopus interactions in some species are more complex than once thought — and throwing things may be one way the animals communicate, the scientists reported.

In the regions of Jervis Bay where gloomy octopuses live, food and materials for shelter are plentiful; outside these patches of suitable habitat, resources are scarce. This could explain the unusual density of octopus populations there, which would, in turn, increase the number of encounters between creatures that would probably prefer to be the only octopus in town. Therefore, throwing debris may be a way for these normally solitary creatures to manage interactions with their octopus neighbors — including unwanted sexual advances, the researchers wrote.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.