Tiny crystals unearthed in South Africa contain evidence of a sudden transition on the planet's surface 3.8 billion years ago.

These crystals, each no bigger than a grain of sand, show that around that time, Earth's crust broke up and began moving — a precursor to the process known as plate tectonics.

The findings offer clues about Earth's evolution as a planet, and could help answer questions about potential links between plate tectonics and the evolution of life, said study lead author Nadja Drabon, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University.

"Earth is the only planet that has life; Earth is the only planet that has plate tectonics," Drabon told Live Science.

Engine of life

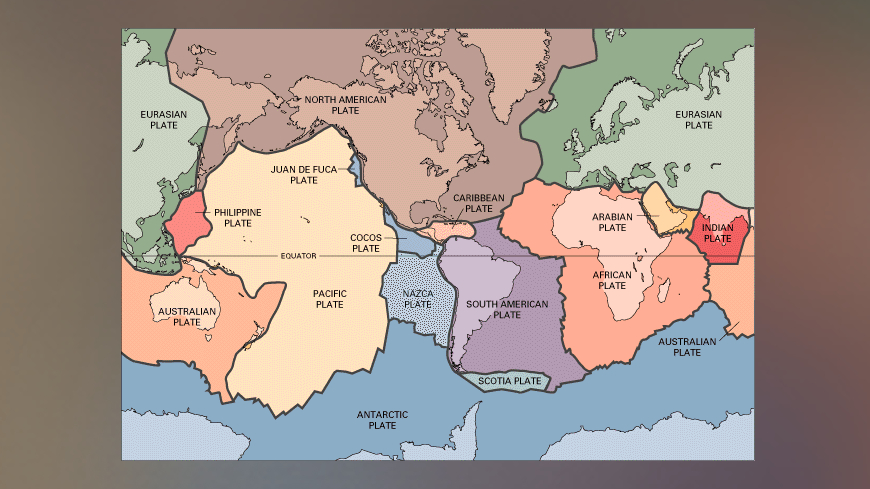

Nowadays, jigsaw pieces of rigid crust float on a viscous, hot ocean of magma in the mantle, Earth's middle layer. These pieces of crust grind against each other, dive beneath each other at so-called subduction zones and push each other up, creating mountains and ocean ridges, forging volcanoes and triggering the earthquakes that regularly rock the planet. The sinking of tectonic plates also produces new rocks at subduction zones, which interact with the atmosphere to suck up carbon dioxide. This process makes the atmosphere more hospitable for life and keeps the climate more stable, Drabon said.

But things weren't always this way. When Earth was young and hot, during the Hadean eon (4.6 billion to 4 billion years ago), the planet was first covered with a magma ocean and then, as the planet cooled, a solid rock surface.

Exactly when that surface cracked and pieces of it began moving has been hotly debated. Some studies estimate plate tectonics began just 800 million years ago, while others suggest this system is at least 2 billion years old, Live Science previously reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But because the planet is constantly recycling its crust into the mantle, there are almost no ancient rocks at the surface to help settle the debate. Prior to this study, "rocks that are between 2.5 [billion] and 4 billion years old only make up 5% of the rocks at the surface," Drabon said. "And earlier than 4 billion years, there are no rocks preserved."

Sudden transition

That changed in 2018, when Drabon and her colleagues discovered zircon crystals in South Africa's Green Sandstone Bed, in the Barberton Greenstone mountain range. The team found 33 zircons, ranging in age between 4.1 billion and 3.3 billion years old.

In the new study, published April 21 in the journal AGU Advances, the team analyzed different isotopes, or variants of elements with different numbers of neutrons, in those ancient zircons, as well as in many zircons from other times and places on Earth.

In the isotopes, the scientists found evidence of a sudden transition to primitive plate tectonics dating to around 3.8 billion years ago. That finding suggests that by that time, in at least one place on the planet, a simple form of subduction had begun. Whether or not this happened globally is still undetermined, and it's likely that the "really efficient engine of plates moving against each other" that exists today hadn't yet emerged, Drabon said.

Isotope analysis of elements such as oxygen, niobium and uranium also showed that rocks from the surface held water as early as 3.8 billion years ago, suggesting that the zircons were once locked in oceanic crust buried in a primeval seafloor. And extrapolating from the earliest samples, from 4.1 billion years ago, suggest that the planet had a solid crust no later than 4.2 billion years ago, Drabon said.

This would mean that Earth's magma sea persisted only until the late Hadean. Previously, "people thought that Earth was just covered by a magma ocean until 3.6 billion years" ago, Drabon said.

The new study hints that Earth's molten lava ocean existed for at most a few hundred million years before the solid crust formed, she added.

So what triggered this transition? One theory is that plate tectonics simply emerged once Earth had cooled enough, she said. It's also possible that, like a dessert spoon cracking the crisp top of a crème brûlée, massive space rocks may have slammed into Earth and shattered its crust.

Another intriguing question addresses if Earth's transition to early plate tectonics somehow helped life evolve, Drabon added.

While early fossil evidence of life on Earth dates to around 3.5 billion years ago, chemical signatures of biological processes, found in the ratio of carbon isotopes, are even older. Some can be found as far back as 3.8 billion years ago — around the same time early plate tectonics emerged, Drabon said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.