Man holding penis and flanked by leopards is world's oldest narrative carving

The 11,000-year-old carved relief, found in Turkey, is the oldest narrative carving on record.

An 11,000-year-old rock-cut relief in southeastern Turkey featuring menacing animals and two men, one of whom is holding his genitalia, is the oldest narrative scene on record, a new study suggests.

Archaeologists discovered the curious carvings on built-in benches within a Neolithic (or New Stone Age) building in the Urfa region. Measuring roughly 2.5 to 3 feet (0.7 to 0.9 meter) tall and 12 feet (3.7 m) long, the newly discovered rock-cut relief showcases two leopards, a bull and the two men — one grasping his phallus and the other holding a rattle or snake.

Whoever carved the wild creatures accentuated their dangerous, pointy parts — the leopards' teeth and the bulls' horns. But exactly what this narrative was meant to convey is lost to time, according to the study, which was published Thursday (Dec. 8) in the journal Antiquity.

Related: Human head carvings and phallus-shaped pillars discovered at 11,000-year-old site in Turkey

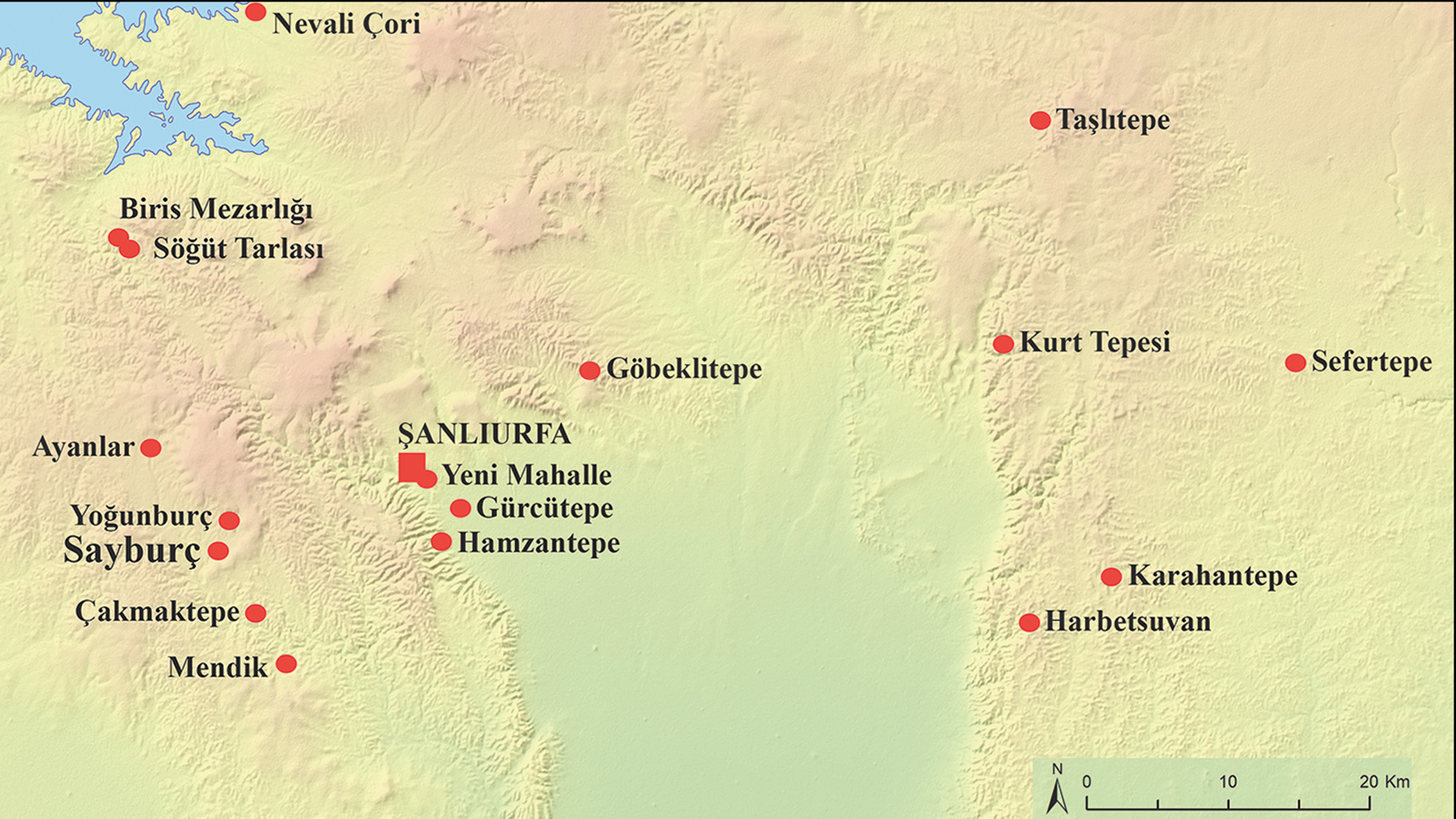

Archaeologists found the carved scene at Sayburç, a Neolithic mound site roughly 35 miles (56 kilometers) east of the Euphrates River and 20 miles (32 km) north of the Syrian border. Sayburç dates to the ninth millennium B.C., a time when hunter-gatherers were shifting to farming and long-term settlements.

Excavation at the site began in 2021 and quickly revealed the ruins of a communal building measuring 36 feet (11 m) in diameter, or about the length of a telephone pole. The building was carved into the limestone bedrock with stone-built walls and benches that rose from the floor. The artwork was found on the front of one of the carved benches, according to Eylem Özdoğan, an archaeologist at Istanbul University and the study's sole author.

According to Özdoğan's research, there are two separate scenes that are meant to be read together as a narrative work of art. Starting from the left are shallow carvings of a bull and a man facing each other. The man has a "phallus-shaped extension on the abdomen," and his "raised, open left hand has six fingers, while the right holds a snake or rattle," she wrote in the paper. The second scene involves two leopards — mouths open, teeth visible, long tails curled up toward the body — facing a man who is carved almost in 3D. He stares into the room rather than to the side and holds his phallus with his right hand.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In terms of technique and craftsmanship," Özdoğan wrote, "the flat relief figures are also comparable to other Pre-Pottery Neolithic images in the region" like those at nearby Göbekli Tepe, a UNESCO World Heritage site known to have the world's oldest megaliths — massive pillars decorated with animals and people. But the Sayburç reliefs differ because the figures form a narrative, suggesting events being related or stories being told, a kind of "reflection of a collective memory that kept the values of its community alive."

In an email to Live Science, Özdoğan explained that "in places such as Göbekli Tepe and Sayburç, there is a masculine world and its reflections — male predatory animals, phalluses, and male depictions. The ones at Sayburç are different in that they are depicted together to form a scene."

Jens Notroff, a Neolithic archaeologist at the German Archaeological Institute who was not involved in this research, agreed that the artwork was meant to convey masculinity. He told Live Science in an email that "the juxtaposition of demonstrating vitality and virility — the phallus presentation — on the one hand and life-threatening danger — snarling predators with bared teeth — on the other seems particularly noteworthy here."

Notroff added that this find may help archaeologists better interpret Neolithic iconography in Turkey. "Unfortunately, while the Neolithic hunter may have easily recognized its message," he said, "we are still lacking an understanding of the actual narrative."

The communal building at Sayburç has only been partially excavated so far. While Özdoğan is confident in the interpretation of the building as a gathering area, she is not sure what they will find as they finish digging. "There may be a scene or other elements on the opposite side" of the bench, she told Live Science.

Notroff is enthusiastic about what future excavations could tell archaeologists about art and society in ancient Turkey. This finding at Sayburç is a "fascinating new insight," he said, and he's "looking forward to seeing more results of ongoing research and excavations on other early Neolithic sites in the Urfa region and beyond."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in anthropology and classical archaeology and was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.