World's oldest 'pet cemetery' discovered in ancient Egypt

One monkey was buried with three kittens, shells and a piglet.

Archaeologists in Egypt have discovered the oldest pet cemetery on record — a nearly 2,000-year-old burial ground filled with well-loved animals, including the remains of cats and monkeys still wearing collars stringed with shell, glass and stone beads, a new study finds.

Ancient Egyptians are known for mummifying countless animals to honor the gods, but this cemetery is different, said study lead researcher Marta Osypińska, a zooarchaeologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. Unlike some mummified animals that were interred at other sites, sometimes through starvation or a snapped neck, none of the creatures in this cemetery — located on the outskirts of the Red Sea port of Berenice — showed signs that they had died at the hands of people.

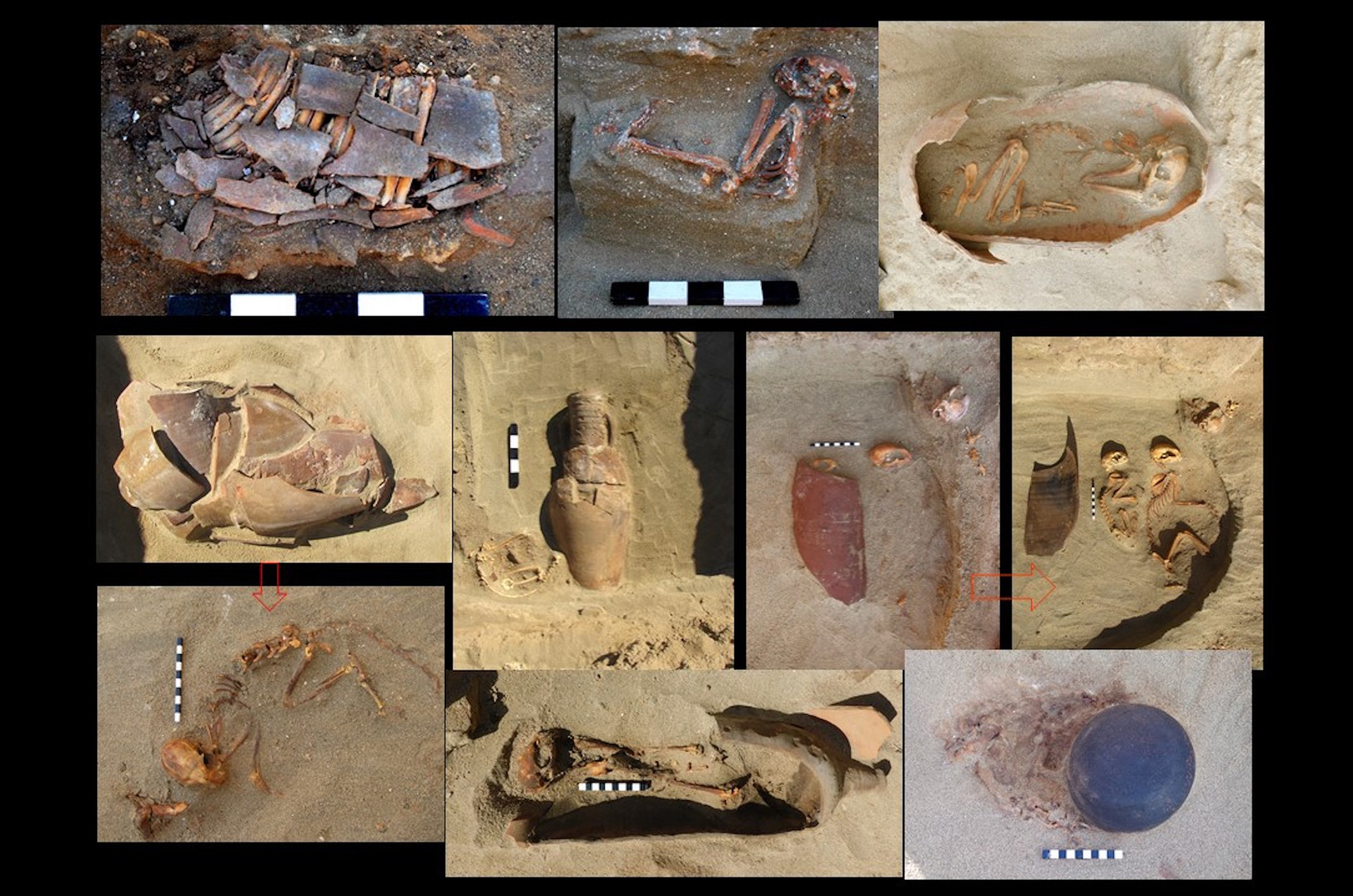

Instead, "we have old, sick and deformed animals that had to be fed and looked after by someone," Osypińska told Live Science in an email. "We have animals (almost all) that are very carefully buried. The animals are placed in a sleeping position — sometimes wrapped in a blanket, sometimes covered with dishes."

In one case, a macaque monkey was buried with three kittens, a grass basket, cloth, vessel fragments (one of which covered a young piglet) and "two very beautiful Indian Ocean shells stacked against its head," Osypińska said. "So, we think that in Berenice the animals were not sacrifices to the gods, but just pets."

Related: Photos: Ancient cat remains tell the tale of kitty domestication

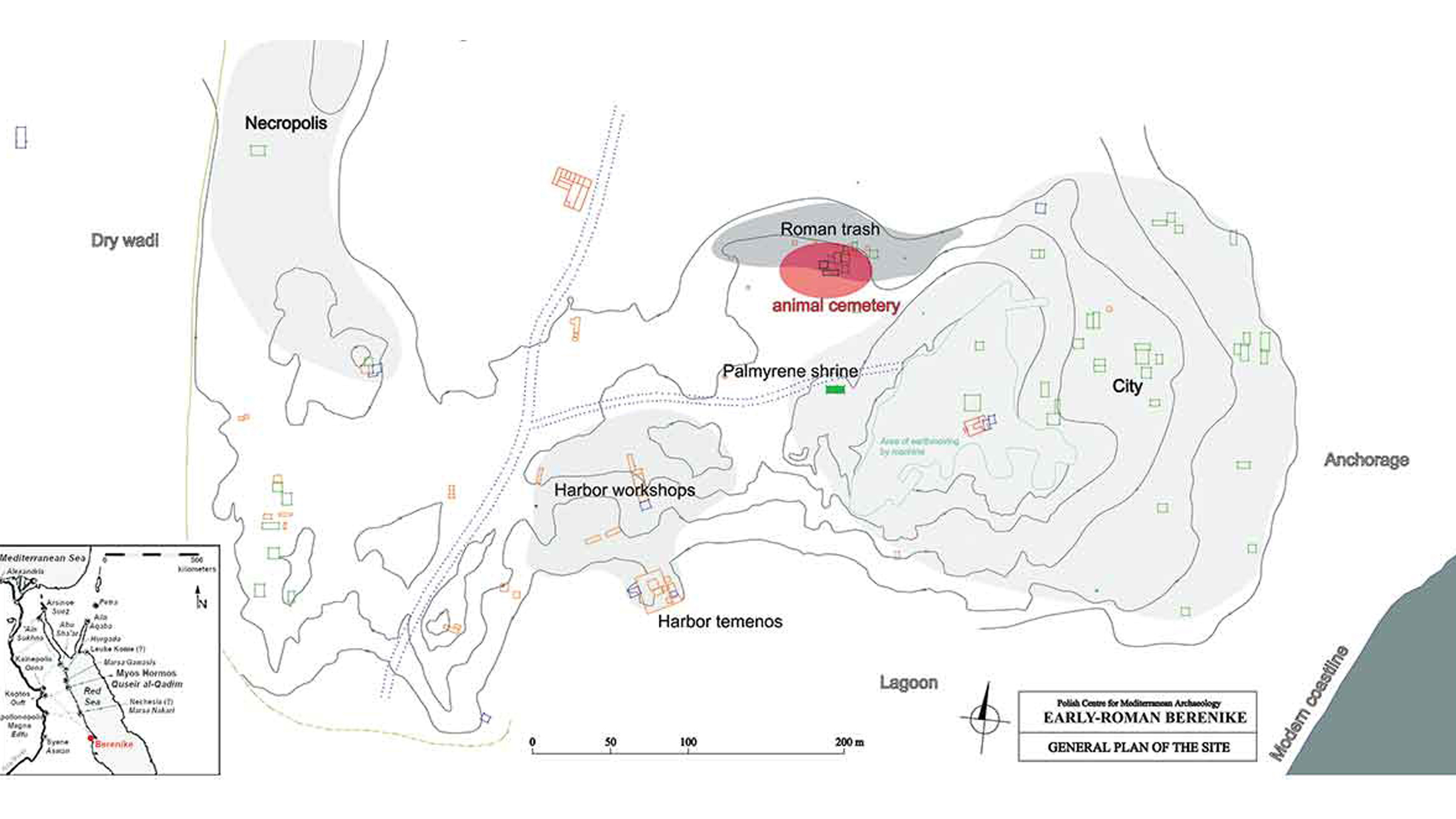

Archaeologists discovered the pet cemetery, which dates to the first and second centuries A.D. during Egypt's early Roman period, by accident. For years, researchers have excavated the outskirts of Berenice because it houses an ancient dump, filled with rubbish from Egyptian society. In 2011, archaeologists began finding the remains of small animals in one area, so they looped in Osypińska because of her speciality in zooarchaeology.

"It turned out to be dozens of cat skeletons," she said. In fact, of the 585 animals they excavated, 536 were cats, 32 dogs, 15 monkeys, one fox and one falcon. None of the animals were mummified, but some were placed in makeshift coffins. For instance, one large dog "was wrapped in a mat of palm leaves and someone had carefully placed two halves of a large vessel (amphora) on his body," just like a sarcophagus, Osypińska said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Just like some pets today, these animals may have worked for their owners, Osypińska said. For instance, cats may have been mousers and the dogs could have helped guard and hunt. But a few of the animals were deformed, meaning they likely couldn't run.

"Someone fed and kept such a 'useless' cat," Osypińska said. Her team also found dogs, some nearly toothless, that made it to old age, and three "toy dogs," smaller than cats, that were likely too small to work.

Other clues indicated these animals were pets, including the fact that many of the cats wore iron-made collars or beaded necklaces, "sometimes very precious and exclusive," Osypińska said. An ostracon, a piece of ceramic with text — like an "antique text message" — found at the site had a note from when some pet cats were still alive, telling an owner not to worry about the cats, because someone else was taking care of them, she added.

Many scholars argue that the ancient world had no concept of "pets," but "our discovery shows that we humans have a deep need for the companionship of animals," Osypińska said. About 2,000 years ago, "the port of Berenice was at the end of the world. It was an empty, hostile piece of the world," she said. "Merchants came here to bring exclusive goods to the empire. What they took on such a long and difficult journey: a beloved dog, or they [had] a monkey brought from India, or kept cats."

The study was published online Jan. 25 in the journal World Archaeology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.