'Pac-Man' microorganisms gobble down viruses like power pellets

If these organisms are eating viruses in nature, it could change the way scientists think about global carbon cycling.

Are viruses the new gourmet meal du jour? Maybe for the tiny, single-celled organisms that live in freshwater bodies around the world.

A new study, published Dec. 27 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, finds that single-celled organisms called Halteria may be munching on viruses like Pac-Man eats pellets — and could possibly change the way scientists think about global carbon cycling.

The viruses in question belong to the genus Chlorovirus genus and are found in essentially every body of freshwater, but mostly in inland water such as lakes and ponds. Chloroviruses infect algae, stuffing the algae full of viruses until they explode. This explosion releases carbon and other nutrients into the environment that would have otherwise been eaten by the algae's predators; instead, these nutrients are made available to other microorganisms.

This micro-recycling, while a bonus for other microorganisms, may not benefit the food chain overall, study first author John DeLong, an ecologist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, said in a statement. Energy generally passes upward through the food chain as predators eat prey that have themselves consumed more simple and basic sources of nutrients, like algae. But when viruses destroy algae, that traps those nutrients at the bottom of the food chain.

"That's really just keeping carbon down in this sort of microbial soup layer, keeping grazers from taking energy up the food chain," DeLong said.

Related: 12 microscopic discoveries that went 'viral' in 2022

With the sheer numbers of viruses and microorganisms teeming in lakes, ponds and other bodies of freshwater, DeLong wondered, is there anything eating viruses and restoring the movement of nutrients up the food chain? In a literature search, he found previous research about virus-eating single-celled organisms called protists, so there was precedent for "virovory," a term that DeLong and his team coined to refer to virus-only diets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"[Viruses are] made up of really good stuff: nucleic acids, a lot of nitrogen and phosphorus," he said. "Everything should want to eat them. So many things will eat anything they can get a hold of. Surely something would have learned how to eat these really good raw materials."

Luckily, samples for his study weren't hard to find. DeLong drove to a nearby pond and took some pond water back to the lab. He concentrated as many microorganisms as he could into drops of water and added a generous helping of Chlorovirus to some of them.

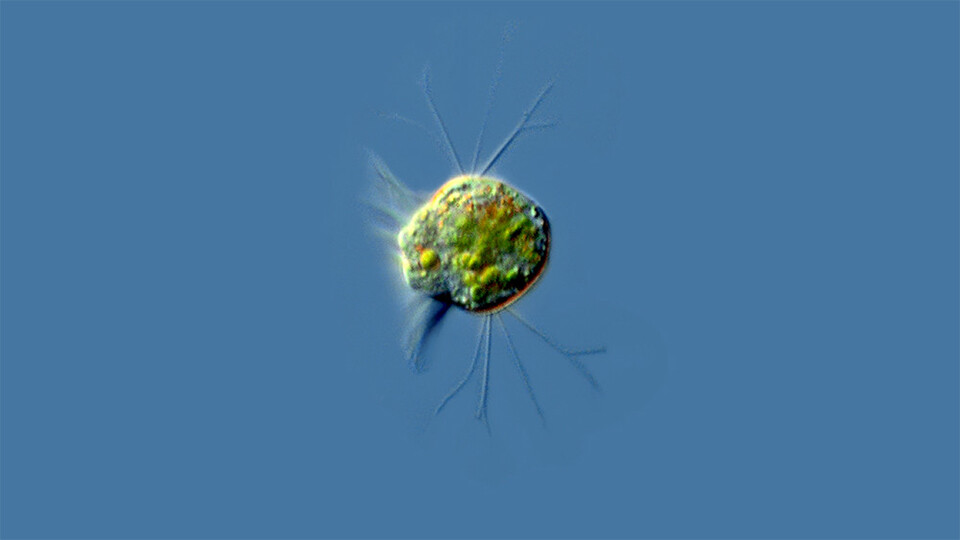

What he found was, devoid of any other food source, Halteria seemed to be chowing down on viruses. The Halteria in a drop of water with viruses grew 15 times their original size within two days, while the number of chloroviruses plummeted. In the water drop without viruses, Halteria did not grow.

To confirm the viruses were eaten by the microscopic Halteria, DeLong's team tagged the chlorovirus's DNA with fluorescent green dye; soon enough, they spotted the glowing viruses in Halteria's vacuole, a structure equivalent to its stomach.

The team was thrilled, but they have more questions to answer, such as do Halteria eat viruses in nature? Or did they just gobble up whatever snack they could find in their small drop of water? Further, what does this potential diet mean for freshwater ecosystems around the globe? DeLong suspects that in a small pond, Halteria and other microorganisms could be eating 10 trillion viruses per day.

"If you multiply a crude estimate of how many viruses there are, how many [microorganisms] there are and how much water there is, it comes out to this massive amount of energy movement (up the food chain)," DeLong said. "If this is happening at the scale that we think it could be, it should completely change our view on global carbon cycling."

JoAnna Wendel is a freelance science writer living in Portland, Oregon. She mainly covers Earth and planetary science but also loves the ocean, invertebrates, lichen and moss. JoAnna's work has appeared in Eos, Smithsonian Magazine, Knowable Magazine, Popular Science and more. JoAnna is also a science cartoonist and has published comics with Gizmodo, NASA, Science News for Students and more. She graduated from the University of Oregon with a degree in general sciences because she couldn't decide on her favorite area of science. In her spare time, JoAnna likes to hike, read, paint, do crossword puzzles and hang out with her cat, Pancake.